The Project Gutenberg EBook of A List To Starboard, by F. Hopkinson Smith

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: A List To Starboard

1909

Author: F. Hopkinson Smith

Illustrator: F. Hopkinson Smith

Release Date: December 3, 2007 [EBook #23702]

Last Updated: March 8, 2018

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A LIST TO STARBOARD ***

Produced by David Widger

A LIST TO STARBOARD

By F. Hopkinson Smith

1909

I

A short, square chunk of a man walked into a shipping office on the East

Side, and inquired for the Manager of the Line. He had kindly blue eyes,

a stub nose, and a mouth that shut to like a rat-trap, and stayed

shut. Under his chin hung a pair of half-moon whiskers which framed his

weather-beaten face as a spike collar frames a dog's.

“You don't want to send this vessel to sea again,” blurted out the

chunk. “She ought to go to the dry-dock. Her boats haven't had a

brushful of paint for a year; her boilers are caked clear to her

top flues, and her pumps won't take care of her bilge water. Charter

something else and lay her up.”

The Manager turned in his revolving chair and faced him. He was the

opposite of the Captain in weight, length, and thickness--a slim,

well-groomed, puffy-cheeked man of sixty with a pair of uncertain, badly

aimed eyes and a voice like the purr of a cat.

“Oh, my dear Captain, you surely don't mean what you say. She is

perfectly seaworthy and sound. Just look at her inspection--” and he

passed him the certificate.

“No--I don't want to see it! I know 'em by heart: it's a lie, whatever

it says. Give an inspector twenty dollars and he's stone blind.”

The Manager laughed softly. He had handled too many rebellious captains

in his time; they all had a protest of some kind--it was either the

crew, or the grub, or the coal, or the way she was stowed. Then he added

softly, more as a joke than anything else:

“Not afraid, are you, Captain?”

A crack started from the left-hand corner of the Captain's mouth,

crossed a fissure in his face, stopped within half an inch of his stub

nose, and died out in a smile of derision.

“What I'm afraid of is neither here nor there. There's cattle

aboard--that is, there will be by to-morrow night; and there's a lot of

passengers booked, some of 'em women and children. It isn't honest to

ship 'em and you know it! As to her boilers send for the Chief Engineer.

He'll tell you. You call it taking risks; I call it murder!”

“And so I understand you refuse to obey the orders of the Board?--and

yet she's got to sail on the 16th if she sinks outside.”

“When I refuse to obey the orders of the Board I'll tell the Board, not

you. And when I do tell 'em I'll tell 'em something else, and that is,

that this chartering of worn-out tramps, painting 'em up and putting 'em

into the Line, has got to stop, or there'll be trouble.”

“But this will be her last trip, Captain. Then we'll overhaul her.”

“I've heard that lie for a year. She'll run as long as they can insure

her and her cargo. As for the women and children, I suppose they don't

count--” and he turned on his heel and left the office.

On the way out he met the Chief Engineer.

“Do the best you can, Mike,” he said; “orders are we sail on the 16th.”

*****

On the fourth day out this conversation took place in the smoking-room

between a group of passengers.

“Regular tub, this ship!” growled the Man-Who-Knew-It-All to the Bum

Actor. “Screw out of the water every souse she makes; lot of dirty

sailors skating over the decks instead of keeping below where they

belong; Chief Engineer loafing in the Captain's room every chance he

gets--there he goes now--and it's the second time since breakfast. And

the Captain is no better! And just look at the accommodations--three

stewards and a woman! What's that to look after thirty-five passengers?

Half the time I have to wait an hour to get something to eat--such as it

is. And my bunk wasn't made up yesterday until plumb night. That bunch

in the steerage must be having a hard time.”

“We get all we pay for,” essayed the Travelling Man. “She ain't rigged

for cabin passengers, and the Captain don't want 'em. Didn't want

to take me--except our folks had a lot of stuff aboard. Had enough

passengers, he said.”

“Well, he took the widow and her two kids”--continued the

Man-Who-Knew-It-All--“and they were the last to get aboard. Half the

time he's playing nurse instead of looking after his ship. Had 'em all

on the bridge yesterday.”

“He _had_ to take 'em,” protested the Travelling Man. “She was put under

his charge by his owners--so one of the stewards told me.”

“Oh!--_had to_, did he! Yes--I've been there before. No use

talking--this line's got to be investigated, and I'm going to do the

investigating as soon as I get ashore, and don't you forget it! What's

your opinion?”

The Bum Actor made no reply. He had been cold and hungry too many days

and nights to find fault with anything. But for the generosity of a few

friends he would still be tramping the streets, sleeping where he could.

Three meals a day--four, if he wanted them--and a bed in a room all to

himself instead of being one in a row of ten, was heaven to him. What

the Captain, or the Engineer, or the crew, or anybody else did, was

of no moment, so he got back alive. As to the widow's children, he

had tried to pick up an acquaintance with them himself--especially

the boy--but she had taken them away when she saw how shabby were his

clothes.

The Texas Cattle Agent now spoke up. He was a tall, raw-boned man, with

a red chin-whisker and red, weather-scorched face, whose clothing looked

as if it had been pulled out of shape in the effort to accommodate

itself to the spread of his shoulders and round of his thighs. His

trousers were tucked in his boots, the straps hanging loose. He

generally sat by himself in one corner of the cramped smoking-room, and

seldom took part in the conversation. The Bum Actor and he had exchanged

confidences the night before, and the Texan therefore felt justified in

answering in his friend's stead.

“You're way off, friend,” he said to the Man-Who-Knew-It-All. “There

ain't nothin' the matter with the Line, nor the ship, nor the Captain.

This is my sixth trip aboard of her, and I know! They had a strike among

the stevedores the day we sailed, and then, too, we've got a scrub lot

of stokers below, and the Captain's got to handle 'em just so. That kind

gets ugly when anything happens. I had sixty head of cattle aboard here

on my last trip over, and some of 'em got loose in a storm, and there

was hell to pay with the crew till things got straightened out. I ain't

much on shootin' irons, but they came handy that time. I helped and I

know. Got a couple in my cabin now. Needn't tell me nothin' about the

Captain. He's all there when he's wanted, and it don't take him more'n a

minute, either, to get busy.”

The door of the smoking-room opened and the object of his eulogy

strolled in. He was evidently just off the bridge, for the thrash of

the spray still glistened on his oilskins and on his gray, half-moon

whiskers. That his word was law aboard ship, and that he enforced it

in the fewest words possible, was evident in every line of his face

and every tone of his voice. If he deserved an overhauling it certainly

would not come from any one on board--least of all from Carhart--the

Man-Who-Knew-It-All.

Loosening the thong that bound his so'wester to his chin, he slapped it

twice across a chair back, the water flying in every direction, and then

faced the room.

“Mr. Bonner.”

“Yes, sir,” answered the big-shouldered Texan, rising to his feet.

“I'd like to see you for a minute,” and without another word the two men

left the room and made their way in silence down the wet deck to where

the Chief Engineer stood.

“Mike, this is Mr. Bonner; you remember him, don't you? You can rely on

his carrying out any orders you give him. If you need another man let

him pick him out--” and he continued on to his cabin.

Once there the Captain closed the door behind him, shutting out the

pound and swash of the sea; took from a rack over his bunk a roll of

charts, spread one on a table and with his head in his hands studied

it carefully. The door opened and the Chief Engineer again stood beside

him. The Captain raised his head.

“Will Bonner serve?” he asked.

“Yes, glad to, and he thinks he's got another man. He's what he calls

out his way a 'tenderfoot,' he says, but he's game and can be depended

on. Have you made up your mind where she'll cross?”--and he bent over

the chart.

The Captain picked up a pair of compasses, balanced them for a moment in

his fingers, and with the precision of a seamstress threading a needle,

dropped the points astride a wavy line known as the steamer track.

The engineer nodded:

“That will give us about twenty-two hours leeway,” he said gravely, “if

we make twelve knots.”

“Yes, if you make twelve knots: can you do it?”

“I can't say; depends on that gang of shovellers and the way they

behave. They're a tough lot--jail-birds and tramps, most of 'em. If

they get ugly there ain't but one thing left; that, I suppose, you won't

object to.”

The Captain paused for a moment in deep thought, glanced at the pin

prick in the chart, and said with a certain forceful meaning in his

voice:

“No--not if there's no other way.”

The Chief Engineer waited, as if for further reply, replaced his cap,

and stepped out into the wind. He had got what he came for, and he had

got it straight.

With the closing of the door the Captain rolled up the chart, laid it

in its place among the others, readjusted the thong of his so'wester,

stopped for a moment before a photograph of his wife and child, looked

at it long and earnestly, and then mounted the stairs to the bridge.

With the exception that the line of his mouth had straightened and

the knots in his eyebrows tightened, he was, despite the smoking-room

critics, the same bluff, determined sea-dog who had defied the Manager

the week before.

II

When Bonner, half an hour later, returned to the smoking-room (he, too,

had caught the splash of the sea, the spray drenching the rail), the Bum

Actor crossed over and took the seat beside him. The Texan was the only

passenger who had spoken to him since he came aboard, and he had already

begun to feel lonely. This time he started the conversation by brushing

the salt spray from the Agent's coat.

“Got wet, didn't you? Too bad! Wait till I wipe it off,” and he dragged

a week-old handkerchief from his pocket. Then seeing that the Texan took

no notice of the attention, he added, “What did the Captain want?”

The Texan did not reply. He was evidently absorbed in something outside

his immediate surroundings, for he continued to sit with bent back, his

elbows on his knees, his eyes on the floor.

Again the question was repeated:

“What did the Captain want? Nothing the matter, is there?” Fear had

always been his master--fear of poverty mostly--and it was poverty in

the worst form to others if he failed to get home. This thought had

haunted him night and day.

“Yes and no. Don't worry--it'll all come out right. You seem nervous.”

“I am. I've been through a lot and have almost reached the end of my

rope. Have you got a wife at home?” The Texan shook his head. “Well,

if you had you'd understand better than I can tell you. I have, and a

three-year-old boy besides. I'd never have left them if I'd known.

I came over under contract for a six months' engagement and we were

stranded in Pittsburg and had hard work getting back to New York. Some

of them are there yet. All I want now is to get home--nothing else will

save them. Here's a letter from her I don't mind showing you--you can

see for yourself what I'm up against. The boy never was strong.”

The big Texan read it through carefully, handed it back without a

comment or word of sympathy, and then, with a glance around him, as if

in fear of being overheard, asked:

“Can you keep your nerve in a mix-up?”

“Do you mean a fight?” queried the Actor.

“Maybe.”

“I don't like fights--never did.” Anything that would imperil his safe

return was to be avoided.

“I neither--but sometimes you've got to. Are you handy with a gun?”

“Why?”

“Nothing--I'm only asking.”

Carhart, the Man-Who-Knew-It-All, here lounged over from his seat by the

table and dropped into a chair beside them, cutting short his reply. The

Texan gave a significant look at the Actor, enforcing his silence, and

then buried his face in a newspaper a month old.

Carhart spread his legs, tilted his head back on the chair, slanted his

stiff-brim hat until it made a thatch for his nose, and began one of his

customary growls: to the room--to the drenched port-holes--to the brim

of his hat; as a half-asleep dog sometimes does when things have gone

wrong with him--or he dreams they have.

“This ship reminds me of another old tramp, the _Persia_,” he drawled.

“Same scrub crew and same cut of a Captain. Hadn't been for two of the

passengers and me, we'd never got anywhere. Had a fire in the lower hold

in a lot of turpentine, and when they put that out we found her cargo

had shifted and she was down by the head about six feet. Then the crew

made a rush for the boats and left us with only four leaky ones to go

a thousand miles. They'd taken 'em all, hadn't been for me and another

fellow who stood over them with a gun.”

The Bum Actor raised his eyes.

“What happened then?” he asked in a nervous voice.

“Oh, we pitched in and righted things and got into port at last. But the

Captain was no good; he'd a-left with the crew if we'd let him.”

“Is the shifting of a cargo a serious matter?” continued the Actor.

“This is my second crossing and I'm not much up on such things.”

“Depends on the weather,” interpolated a passenger.

“And on how she's stowed,” continued Car-hart. “I've been mistrusting

this ship ain't plumb on her keel. You can tell that from the way she

falls off after each wave strikes her. I have been out on deck looking

things over and she seems to me to be down by the stern more than she

ought.”

“Maybe she'll be lighter when more coal gets out of her,” suggested

another passenger.

“Yes, but she's listed some to starboard. I watched her awhile this

morning. She ain't loaded right, or she's loaded _wrong,-purpose_. That

occurs sometimes with a gang of striking stevedores.”

The noon whistle blew and the talk ended with the setting of everybody's

watch, except the Bum Actor's, whose timepiece decorated a shop-window

in the Bowery.

*****

That night one of those uncomfortable rumors, started doubtless by

Carhart's talk, shivered through the ship, its vibrations even reaching

the widow lying awake in her cabin. This said that some hundreds of

barrels of turpentine had broken loose and were smashing everything

below. If any one of them rolled into the furnaces an explosion would

follow which would send them all to eternity. That this absurdity was

immediately denied by the purser, who asserted with some vehemence that

there was not a gallon of turpentine aboard, did not wholly allay the

excitement, nor did it stifle the nervous anxiety which had now taken

possession of the passengers.

As the day wore on several additional rumors joined those already

extant. One was dropped in the ear of the Texan by the Bum Actor as the

two stood on the upper deck watching the sea, which was rapidly falling.

“I got so worried I thought I'd go down into the engine room myself,”

he whispered. “I'm just back. Something's wrong down there, or I'm

mistaken. I wish you'd go and find out. I knew that turpentine yarn was

a lie, but I wanted to be sure, so I thought I'd ask one of the stokers

who had come up for a little air. He was about to answer me when the

Chief Engineer came down from the bridge, where he had been talking to

the Captain, and ordered the man below before he had time to fill his

lungs. I waited a little while, hoping he or some of the crew would

come up again, and then I went down the ladder myself. When I got to the

first landing I came bump up against the Chief Engineer. He was standing

in the gangway fooling with a revolver he had in his hand as if he'd

been cleaning it. 'I'll have to ask you to get back where you came

from,' he said. 'This ain't no place for passengers'--and up I came.

What do you think it means? I'd get ugly, too, if he kept me in that

heat and never let me get a whiff of air. I tell you, that's an awful

place down there. Suppose you go and take a look. Your knowing the

Captain might make some difference.”

“Were any of the stokers around?” “No--none of them. I didn't see a soul

but the Chief Engineer, and I didn't see him more than a minute.”

The big Texan moved closer to the rail and again scrutinized the

sky-line. He had kept this up all the morning, his eye searching

the horizon as he moved from one side of the ship to the other. The

inspection over, he slipped his arm through the Actor's and started him

down the deck toward the Cattle Agent's cabin. When the two emerged the

Texan's face still wore the look which had rested on it since the

time the Captain had called him from the smoking-room. The Actor's

countenance, however, had undergone a change. All his nervous timidity

was gone; his lips were tightly drawn, the line of the jaw more

determined. He looked like a man who had heard some news which had first

steadied and then solidified him. These changes often overtake men of

sensitive, highly strung natures.

On the way back they encountered the Captain accompanied by the Chief

Engineer. The two were heading for the saloon, the bugle having sounded

for luncheon. As they passed by with their easy, swinging gait, the

passengers watched them closely. If there was danger in the air these

two officers, of all men, would know it. The Captain greeted the Texan

with a significant look, waited until the Actor had been presented,

looked the Texan's friend over from head to foot, and then with a nod to

several of the others halted opposite a steamer chair in which sat the

widow and her two children--one a baby and the other a boy of four--a

plump, hugable little fellow, every inch of whose surface invited a

caress.

“Please stay a minute and let me talk to you, Captain,” the widow

pleaded. “I've been so worried. None of these stories are true, are

they? There can't be any danger or you would have told me--wouldn't

you?”

The Captain laughed heartily, so heartily that even the Chief Engineer

looked at him in astonishment. “What stories do you hear, my dear lady?”

“That the steamer isn't loaded properly?”

Again the Captain laughed, this time under the curls of the chubby boy

whom he had caught in his arms and was kissing eagerly.

“Not loaded right?” he puffed at last when he got his breath. “Well,

well, what a pity! That yarn, I guess, comes from some of the navigators

in the smoking-room. They generally run the ship. Here, you little

rascal, turn out your toes and dance a jig for me. No--no--not that

way--this way-r-out with them! Here, let me show you. One--two--off

we go. Now the pigeon wing and the double twist and the rat-tat-tat,

rat-tat-tat--that's the way, my lad!”

He had the boy's hands now, the child shouting with laughter, the

overjoyed mother clapping her hands as the big burly Captain with his

face twice as red from the exercise, danced back and forth across the

deck, the passengers forming a ring about them.

“There!” sputtered the Captain, all out of breath from the exercise, as

he dropped the child back into the widow's arms. “Now all of you come

down to luncheon. The weather is getting better every minute. The glass

is rising and we are going to have a fine night.”

Carhart, who had watched the whole performance with an ill-concealed

sneer on his face, muttered to the man next him:

“What did I tell you? He's a pretty kind of a Captain, ain't he? He's

mashed on the widow just as I told you. Smoking-room yarn, is it? I bet

I could pick out half a dozen men right in them chairs who could run

the ship as well as he does. Maybe we'll have to take charge, after

all--don't you think so, Mr. Bonner?”

The Texan smiled grimly: “I'll let you do the picking, Mr. Carhart--”

and with his hand on the Actor's arm, the two went below.

A counter-current now swept through the ship. If anything was really

the matter the Captain would not be dancing jigs, nor would he leave

the bridge for his meals. This, like all other counter-currents--wave or

otherwise--tossed up a bobble of dispute when the two clashed. There

was no doubt about it: Carhart had been “talking through his

hat”--“shooting off his mouth”--the man was “a gas bag,” etc., etc. When

appeal for confirmation was made to the Texan and the Actor, who now

seemed inseparable, neither made reply. They evidently did not care to

be mixed up in what Bonner characterized with a grim smile as “more hot

air.”

All through the meal the Captain kept up his good-natured mood; chatting

with the widow who sat on his right, the baby in her lap; making a pig

of a lemon and some tooth-picks for the boy, who had crawled up into

his arms; exchanging nods and smiles down the length of the table with

several new arrivals, or congratulating those nearest to him on their

recovery after the storm, ending by carrying both boy and baby to the

upper deck--so that he might “not forget how to handle” his own when he

got back, he laughed in explanation.

III

Luncheon over, the passengers, many of whom had been continuously in

their berths, began to crowd the decks. These soon discovered that the

ship was not on an even keel; a fact confirmed when attention was called

to the slant of the steamer chairs and the roll of an orange toward the

scuppers. Explanation was offered by the Texan, who argued that the

wind had hauled, and being then abeam had given her a list to starboard.

This, while not wholly satisfactory to the more experienced, allayed

the fears of the women--there were two or three on board beside the

widow--who welcomed the respite from the wrench and stagger of the

previous hours.

Attention was now drawn by a nervous passenger to a gang of sailors

under the First Officer, who were at work overhauling the boats on the

forward deck, immediately under the eyes of the Captain who had returned

to the bridge, as well as to an approaching wall of fog which, while he

was speaking, had blanketed the ship, sending two of the boat gang on

a run to the bow. The fog-horn also blew continuously, almost without

intermission. Now and then it too would give three short, sharp snorts,

as if of warning.

The passengers had now massed themselves in groups, some touch of

sympathy, or previous acquaintance, or trait of courage but recently

discovered, having drawn them together. Again the Captain passed down

the deck. This time he stopped to light a cigarette from a passenger's

cigar, remarking as he did so that it was “as thick as pea soup on the

bridge, but he thought it would lighten before morning.” Then halting

beside the chair of an old lady who had but recently appeared on deck,

he congratulated her on her recovery and kept on his way to the boats.

The widow, however, was still anxious.

“What are they doing with the boats?” she asked, her eyes following the

Captain's disappearing figure.

“Only overhauling them, madam,” spoke up the Texan, who had stationed

himself near her chair.

“But isn't that unusual!” she inquired in a tremulous voice.

“No, madam, just precaution, and always a safe one in a fog. Collision

comes so quick sometimes they don't have time even to clear the davits.”

“But the sailors are carrying up boxes and kegs and putting them in

the boats; what's that for?” broke in another passenger, who had been

leaning over the forward rail.

“Grub and water, I guess,” returned the Texan. “It's a thousand miles to

the nearest land, and there ain't no bakery on the way that I know of.

Can't be too careful when there's women and babies aboard, especially

little fellows like these--” and he ran his hand through the boy's

curls. “The Captain don't take no chances. That's what I like him for.”

Again the current of hope submerged the current of despair. The slant of

the deck, however, increased, although the wind had gone down; so

much so that the steamer chairs had to be lashed to the iron hand-hold

skirting the wall of the upper cabins. So had the fog, which was now so

dense that it hid completely the work of the boat gang.

With the passing of the afternoon and the approach of night, thus

deepening the gloom, there was added another and a new anxiety to the

drone of the fog-horn. This was a Coston signal which flashed from the

bridge, flooding the deck with light and pencilling masts and rigging in

lines of fire. These flashes kept up at intervals of five minutes, the

colors changing from time to time.

An indefinable fear now swept through the vessel. The doubters and

scoffers from the smoking-room who stood huddled together near the

forward companion-way talked in whispers. The slant of the deck they

argued might be due to a shift of the cargo--a situation serious, but

not dangerous--but why burn Costons? The only men who seemed to be

holding their own, and who were still calm and undisturbed, were the

Texan and the Actor. These, during the conference, had moved toward the

flight of steps leading to the bridge and had taken their positions near

the bottom step, but within reach of the widow's chair. Once the Actor

loosened his coat and slipped in his hand as if to be sure of something

he did not want to lose.

While this was going on the Captain left the bridge in charge of the

Second Officer and descended to his cabin. Reaching over his bunk, he

unhooked the picture of his wife and child, tore it from its frame,

looked at it intently for a moment, and then, with a sigh, slid it into

an inside pocket. This done, he stripped off his wet storm coat, thrust

his arms into a close-fitting reefing jacket, unhooked a holster from

its place, dropped its contents into his outside pocket, and walked

slowly down the flight of steps to where the Texan and the Actor stood

waiting.

Then, facing the passengers, and in the same tone of voice with which he

would have ordered a cup of coffee from a steward, he said:

“My friends, I find it necessary to abandon the ship. There is time

enough and no necessity for crowding. The boats are provisioned for

thirty days. The women and children will go first: this order will be

literally carried out; those who disobey it will have to be dealt with

in another way. This, I hope, you will not make necessary. I will also

tell you that I believe we are still within the steamer zone, although

the fog and weather have prevented any observation. Do you stay here,

madam. I'll come for you when I am ready--” and he laid his hand

encouragingly on the widow's arm.

With this he turned to the Texan and the Actor:

“You understand, both of you, do you not, Mr. Bonner? You and your

friend will guard the aft companion-way, and help the Chief Engineer

take care of the stokers and the steerage. I and the First Officer will

fill the boats.”

The beginning of a panic is like the beginning of a fire: first a curl

of smoke licking through a closed sash, then a rush of flame, and then a

roar freighted with death. Its subduing is along similar lines: A sharp

command clearing the way, concentrated effort, and courage.

Here the curl of smoke was an agonized shriek from an elderly woman who

fell fainting on the deck; the rush of flame was a wild surge of men

hurling themselves toward the boats, and the roar which meant death was

the frenzied throng of begrimed half-naked stokers and crazed emigrants

who were wedged in a solid mass in the companion-way leading to the

upper deck. The subduing was the same.

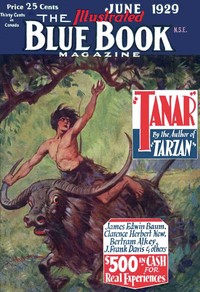

[Illustration: Back, all of you ]

“Back, all of you!” shouted the Engineer. “The first man who passes

that door without my permission I'll kill! Five of you at a time--no

crowding--keep 'em in line, Mr. Bonner--you and your friend!”

The Texan and the Bum Actor were within three feet of him as he

spoke--the Texan as cool as if he were keeping count of a drove of

steers, except that he tallied with the barrel of a six-shooter instead

of a note-book and pencil. The Bum Actor's face was deathly white and

his pistol hand trembled a little, but he did not flinch. He ranged the

lucky ones in line farther along, and kept them there. “Anything to

get home,” he had told the Texan when he had slipped Bonner's other

revolver, an hour before, into his pocket.

On the saloon deck the flame of fear was still raging, although the

sailors and the three stewards were so many moving automatons under

the First Officer's orders. The widow, with her baby held tight to her

breast, had not moved from where the Captain had placed her, nor had

she uttered a moan. The crisis was too great for anything but implicit

obedience. The Captain had kept his word, and had told her when danger

threatened; she must now wait for what God had in store for her. The boy

stood by the First Officer; he had clapped his hands and laughed when he

saw the first boat swung clear of the davits.

Carhart was the color of ashes and could hardly articulate. He had edged

up close to the gangway where the boats were to be filled. Twice he had

tried to wedge himself between the First Officer and the rail and twice

had been pushed back--the last time with a swing that landed him against

a pile of steamer chairs.

All this time the fog-horn had kept up its monotonous din, the Costons

flaring at intervals. The stoppage of either would only have added to

the terror now partly allayed by the Captain's encouraging talk, which

was picked up and repeated all over the ship.

The first boat was now ready for passengers.

“This way, madam--you first--” the Captain said to the widow. “You must

go alone with the baby, and I--”

He did not finish the sentence. Something had caught his ear--something

that made him lunge heavily toward the rail, his eyes searching the

gloom, his hand cupped to his ear.

“Hold hard, men!” he cried. “Keep still-all of you!”

[Illustration: Hold hard men ]

Out of the stillness of the night came the moan of a distant fog-horn.

This was followed by a wild cheer from the men at the boat davits. At

the same instant a dim, far-away light cut its way through the black

void, burned for a moment, and disappeared like a dying star.

Another cheer went up. This time the watch on the foretop and the men

astride the nose sent it whirling through the choke and damp with an

added note of joy.

The Captain turned to the widow.

“That's her--that's the _St. Louis!_ I've been hoping for her all day,

and didn't give up until the fog shut in.”

“And we can stay here!”

“No--we haven't a moment to lose. Our fires are nearly out now. We've

been in a sinking condition for forty-eight hours. We sprung a leak

where we couldn't get at it, and our pumps are clogged.

“Stand aside, men! All ready, madam! No, you can't manage them

both--give me the boy,--I'll bring him in the last boat.”

End of Project Gutenberg's A List To Starboard, by F. Hopkinson Smith

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A LIST TO STARBOARD ***

***** This file should be named 23702-0.txt or 23702-0.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/2/3/7/0/23702/

Produced by David Widger

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase “Project

Gutenberg”), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. “Project Gutenberg” is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation (“the Foundation”

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase “Project Gutenberg” appears, or with which the phrase “Project

Gutenberg” is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase “Project Gutenberg” associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

“Plain Vanilla ASCII” or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original “Plain Vanilla ASCII” or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, “Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation.”

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

“Defects,” such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the “Right

of Replacement or Refund” described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, is critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

[email protected]. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

[email protected]

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.

A List To Starboard - 1909

Subjects:

Download Formats:

Excerpt

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A List To Starboard, by F. Hopkinson Smith

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Release Date: December 3, 2007 [EBook #23702]

Last Updated: March 8, 2018

Read the Full Text

— End of A List To Starboard - 1909 —

Book Information

- Title

- A List To Starboard - 1909

- Author(s)

- Smith, Francis Hopkinson

- Language

- English

- Type

- Text

- Release Date

- December 3, 2007

- Word Count

- 8,625 words

- Library of Congress Classification

- PS

- Bookshelves

- Browsing: Literature, Browsing: Fiction

- Rights

- Public domain in the USA.

Related Books

Famous stories from foreign countries

English

494h 26m read

The incredible slingshot bombs

by Williams, Robert Moore

English

96h 4m read

The eater of souls

by Kuttner, Henry

English

22h 19m read

Maehoe

by Leinster, Murray

English

115h 53m read

The air splasher

by Watkins, Richard Howells

English

138h 53m read

Hooking a sky ride

by Morrissey, Dan

English

37h 54m read