*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 73843 ***

A VOICE FROM HARPER’S FERRY.

A

NARRATIVE OF EVENTS

AT

HARPER’S FERRY;

WITH

INCIDENTS PRIOR AND SUBSEQUENT TO ITS CAPTURE BY

CAPTAIN BROWN AND HIS MEN.

BY

OSBORNE P. ANDERSON,

ONE OF THE NUMBER.

BOSTON:

PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR.

1861.

PREFACE.

My sole purpose in publishing the following Narrative is to save from

oblivion the facts connected with one of the most important movements

of this age, with reference to the overthrow of American slavery. My

own personal experience in it, under the orders of Capt. Brown, on

the 16th and 17th of October, 1859, as the only man alive who was at

Harper’s Ferry during the entire time--the unsuccessful groping after

these facts, by individuals, impossible to be obtained, except from

an actor in the scene--and the conviction that the cause of impartial

liberty requires this duty at my hands--alone have been the motives for

writing and circulating the little book herewith presented.

I will not, under such circumstances, insult nor burden the intelligent

with excuses for defects in composition, nor for the attempt to give

the facts. A plain, unadorned, truthful story is wanted, and that by

one who knows what he says, who is known to have been at the great

encounter, and to have labored in shaping the same. My identity as a

member of Capt. Brown’s company cannot be questioned, successfully, by

any who are bent upon suppressing the truth; neither will it be by any

in Canada or the United States familiar with John Brown and his plans,

as those know his men personally, or by reputation, who enjoyed his

confidence sufficiently to know thoroughly his plans.

The readers of this narrative will therefore keep steadily in view

the main point--that they are perusing a story of events which have

happened under the eye of the great Captain, or are incidental thereto,

and _not_ a compendium of the “plans” of Capt. Brown; for as his

plans were not consummated, and as their fulfilment is committed to

the future, no one to whom they are known will recklessly expose all

of them to the public gaze. Much has been given as true that never

happened; much has been omitted that should have been made known; many

things have been left unsaid, because, up to within a short time, but

two could say them; one of them has been offered up, a sacrifice to

the Moloch, Slavery; being that other one, I propose to perform the

duty, trusting to that portion of the public who love the right for an

appreciation of my endeavor.

O. P. A.

A VOICE FROM HARPER’S FERRY.

CHAPTER I.

THE IDEA AND ITS EXPONENTS--JOHN BROWN ANOTHER MOSES.

The idea underlying the outbreak at Harper’s Ferry is not peculiar to

that movement, but dates back to a period very far beyond the memory of

the “oldest inhabitant,” and emanated from a source much superior to

the Wises and Hunters, the Buchanans and Masons of to-day. It was the

appointed work for life of an ancient patriarch spoken of in Exodus,

chap, ii., and who, true to his great commission, failed not to trouble

the conscience and to disturb the repose of the Pharaohs of Egypt with

that inexorable, “Thus saith the Lord: Let my people go!” until even

they were urgent upon the people in its behalf. Coming down through the

nations, and regardless of national boundaries or peculiarities, it has

been proclaimed and enforced by the patriarch and the warrior of the

Old World, by the enfranchised freeman and the humble slave of the New.

Its nationality is universal; its language every where understood by

the haters of tyranny; and those that accept its mission, every where

understand each other. There is an unbroken chain of sentiment and

purpose from Moses of the Jews to John Brown of America; from Kossuth,

and the liberators of France and Italy, to the untutored Gabriel, and

the Denmark Veseys, Nat Turners and Madison Washingtons of the Southern

American States. The shaping and expressing of a thought for freedom

takes the same consistence with the colored American--whether he be

an independent citizen of the Haytian nation, a proscribed but humble

nominally free colored man, a patient, toiling, but hopeful slave--as

with the proudest or noblest representative of European or American

civilization and Christianity. Lafayette, the exponent of French honor

and political integrity, and John Brown, foremost among the men of

the New World in high moral and religious principle and magnanimous

bravery, embrace as brothers of the same mother, in harmony upon the

grand mission of liberty; but, while the Frenchman entered the lists in

obedience to a desire to aid, and by invitation from the Adamses and

Hamiltons, and thus pushed on the political fortunes of those able to

help themselves, John Brown, the liberator of Kansas, the projector and

commander of the Harper’s Ferry expedition, saw in the most degraded

slave a man and a brother, whose appeal for his God-ordained rights

no one should disregard; in the toddling slave child, a captive whose

release is as imperative, and whose prerogative is as weighty, as

the most famous in the land. When the Egyptian pressed hard upon the

Hebrew, Moses slew him; and when the spirit of slavery invaded the fair

Territory of Kansas, causing the Free-State settlers to cry out because

of persecution, old John Brown, famous among the men of God for ever,

though then but little known to his fellow-men, called together his

sons and went over, as did Abraham, to the unequal contest, but on the

side of the oppressed white men of Kansas that were, and the black men

that were to be. To-day, Kansas is free, and the verdict of impartial

men is, that to John Brown, more than any other man, Kansas owes her

present position.

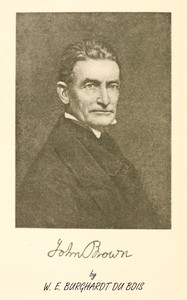

I am not the biographer of John Brown, but I can be indulged in giving

here the opinion common among my people of one so eminently worthy of

the highest veneration. Close observation of him, during many weeks,

and under his orders at his Kennedy-Farm fireside, also, satisfies me

that in comparing the noble old man to Moses, and other men of piety

and renown, who were chosen by God to his great work, none have been

more faithful, none have given a brighter record.

CHAPTER II.

PRELIMINARIES TO INSURRECTION--WHAT MAY BE TOLD AND WHAT NOT--JOHN

BROWN’S FIRST VISIT TO CHATHAM--SOME OF THE SECRETS FROM THE

“CARPET-BAG.”

To go into particulars, and to detail reports current more than a year

before the outbreak, among the many in the United States and Canada

who had an inkling of some “practical work” to be done by “Osawattomie

Brown,” when there should be nothing to do in Kansas,--to give facts

in that connection, would only forestall future action, without

really benefitting the slave, or winning over to that sort of work

the anti-slavery men who do not favor physical resistance to slavery.

Slaveholders alone might reap benefits; and for one, I shall throw none

in their way, by any indiscreet avowals; they already enjoy more than

their share; but to a clear understanding of all the facts to be here

published, it may be well to say, that preliminary arrangements were

made in a number of places,--plans proposed, discussed and decided

upon, numbers invited to participate in the movement, and the list of

adherents increased. Nine insurrections is the number given by some

as the true list of outbreaks since slavery was planted in America;

whether correct or not, it is certain that preliminaries to each

are unquestionable. Gabriel, Vesey, Nat Turner, all had conference

meetings; all had their plans; but they differ from the Harper’s

Ferry insurrection in the fact that neither leader nor men, in the

latter, divulged ours, when in the most trying of situations. Hark

and another met Nat Turner in secret places, after the fatigues of a

toilsome day were ended; Gabriel promulged his treason in the silence

of the dense forest; but John Brown reasoned of liberty and equality in

broad daylight, in a modernized building, in conventions with closed

doors, in meetings governed by the elaborate regulations laid down by

Jefferson, and used as their guides by Congresses and Legislatures; or

he made known the weighty theme, and his comprehensive plans resulting

from it, by the cosy fireside, at familiar social gatherings of chosen

ones, or better, in the carefully arranged junto of earnest, practical

men. Vague hints, careful blinds, are Nat Turner’s entire make-up

to save detection; the telegraph, the post-office, the railway, all

were made to aid the new outbreak. By this, it will be seen that

Insurrection has its progressive side, and has been elevated by John

Brown from the skulking, fearing cabal, when in the hands of a brave

but despairing few, to the highly organized, formidable, and to very

many, indispensable institution for the security of freedom, when

guided by intelligence.

So much as relates to prior movements may safely be said above; but who

met--when they met--where they met--how many yet await the propitious

moment--upon whom the mantle of John Brown has fallen to lead on the

future army--the certain, terribly certain, many who must follow up the

work, forgetting not to gather up the blood of the hero and his slain,

to the humble bondman there offered--these may not, must not be told!

Of the many meetings in various places, before the work commenced, I

shall speak just here of the one, the minutes of which were dragged

forth by marauding Virginians from the “archives” at Kennedy Farm; not

forgetting, however, for their comfort, that the Convention was one

of a series at Chatham, some of which were of equally great, if not

greater, importance.

The first visit of John Brown to Chatham was in April, 1858. Wherever

he went around, although an entire stranger, he made a profound

impression upon those who saw or became acquainted with him. Some

supposed him to be a staid but modernized Quaker; others, a solid

business man, from “somewhere,” and without question a philanthropist.

His long white beard, thoughtful and reverent brow and physiognomy, his

sturdy, measured tread, as he circulated about with hands, as portrayed

in the best lithograph, under the pendant coat-skirt of plain brown

Tweed, with other garments to match, revived to those honored with his

acquaintance and knowing to his history, the memory of a Puritan of the

most exalted type.

After some important business, preparatory to the Convention, was

finished, Mr. Brown went West, and returned with his men, who had been

spending the winter in Iowa. The party, including the old gentleman,

numbered twelve,--as brave, intelligent and earnest a company as could

have been associated in one party. There were John H. Kagi, Aaron D.

Stevens, Owen Brown, Richard Realf, George B. Gill, C. W. Moffitt, Wm.

H. Leeman, John E. Cook, Stewart Taylor, Richard Richardson, Charles

P. Tidd and J. S. Parsons--all white except Richard Richardson, who

was a slave in Missouri until helped to his liberty by Captain Brown.

At a meeting held to prepare for the Convention and to examine the

Constitution, Dr. M. R. Delany was Chairman, and John H. Kagi and

myself were the Secretaries.

When the Convention assembled, the minutes of which were seized by

the slaveholding “cravens” at the Farm, and which, as they have been

identified, I shall append to this chapter, Mr. Brown unfolded his

plans and purpose. He regarded slavery as a state of perpetual war

against the slave, and was fully impressed with the idea that himself

and his friends had the right to take liberty, and to use arms in

defending the same. Being a devout Bible Christian, he sustained

his views and shaped his plans in conformity to the Bible; and when

setting them forth, he quoted freely from the Scripture to sustain his

position. He realized and enforced the doctrine of destroying the tree

that bringeth forth corrupt fruit. Slavery was to him the corrupt tree,

and the duty of every Christian man was to strike down slavery, and to

commit its fragments to the flames. He was listened to with profound

attention, his views were adopted, and the men whose names form a part

of the minutes of that in many respects extraordinary meeting, aided

yet further in completing the work.

MINUTES OF THE CONVENTION.

CHATHAM, (Canada West,) }

Saturday, May 8, 1858--10, A. M. }

Convention met in pursuance to a call of John Brown and others, and

was called to order by Mr. Jackson, on whose motion, Mr. William C.

Munroe was chosen President; when, on motion of Mr. Brown, Mr. J. H.

Kagi was elected Secretary.

On motion of Mr. Delany, Mr. Brown then proceeded to state the object

of the Convention at length, and then to explain the general features

of the plan of action in the execution of the project in view by the

Convention. Mr. Delany and others spoke in favor of the project and

the plan, and both were agreed to by general consent.

Mr. Brown then presented a plan of organization, entitled “Provisional

Constitution and Ordinances for the People of the United States,” and

moved the reading of the same.

Mr. Kinnard objected to the reading until an oath of secrecy was

taken by each member of the Convention; whereupon Mr. Delany moved

that the following parole of honor be taken by all the members of the

Convention--“I solemnly affirm that I will not in any way divulge any

of the secrets of this Convention, except to persons entitled to know

the same, on the pain of forfeiting the respect and protection of this

organization;” which motion was carried.

The President then proceeded to administer the obligation, after

which the question was taken on the reading of the plan proposed by

Mr. Brown, and the same carried.

The plan was then read by the Secretary, after which, on motion of

Mr. Whipple, it was ordered that it be now read by articles for

consideration.

The articles from one to forty-five, inclusive, were then read and

adopted. On the reading of the forty-sixth, Mr. Reynolds moved to

strike out the same. Reynolds spoke in favor, and Brown, Munroe, Owen

Brown, Delany, Realf, Kinnard and Kagi against. The question was then

taken and lost, there being but one vote in the affirmative. The

article was then adopted.

The forty-seventh and forty-eighth articles, with the schedule, were

then adopted in the same manner. It was then moved by Mr. Delany that

the title and preamble stand as read. Carried.

On motion of Mr. Kagi, the Constitution, as a whole, was then

unanimously adopted.

The Convention then, at half-past one o’clock, P. M., adjourned, on

motion of Mr. Jackson, till three o’clock.

* * * * *

THREE O’CLOCK, P. M. Journal read and approved.

On motion of Mr. Delany, it was then ordered that those approving of

the Constitution as adopted sign the same; whereupon the names of all

the members were appended.

After congratulatory remarks by Messrs. Kinnard and Delany, the

Convention, on motion of Mr. Whipple, adjourned at three and

three-quarters o’clock.

J. H. KAGI, _Secretary of the Convention_.

The above is a journal of the Provisional Constitutional Convention

held at Chatham, Canada West, May 8, 1858, as herein stated.

* * * * *

CHATHAM, (Canada West,) Saturday, May 8, 1858.

SIX, P. M. In accordance with, and obedience to, the provisions of the

schedule to the Constitution for the proscribed and oppressed people

“of the United States of America,” to-day adopted at this place, a

Convention was called by the President of the Convention framing

that instrument, and met at the above-named hour, for the purpose of

electing officers to fill the offices specially established and named

by said Constitution.

The Convention was called to order by Mr. M. R. Delany, upon whose

nomination, Mr. Wm. C. Munroe was chosen President, and Mr. J. H.

Kagi, Secretary.

A Committee, consisting of Messrs. Whipple, Kagi, Bell, Cook and

Munroe, was then chosen to select candidates for the various offices

to be filled, for the consideration of the Convention.

On reporting progress, and asking leave to sit again, the request was

refused, and Committee discharged.

On motion of Mr. Bell, the Convention then went into the election of

officers, in the following manner and order:--

Mr. Whipple nominated John Brown for Commander-in-Chief, who, on the

seconding of Mr. Delany, was elected by acclamation.

Mr. Realf nominated J. H. Kagi for Secretary of War, who was elected

in the same manner.

On motion of Mr. Brown, the Convention then adjourned to 9, A. M., on

Monday, the 10th.

* * * * *

MONDAY, May 10, 1858--9, A. M. The proceedings of the Convention on

Saturday were read and approved.

The President announced that the business before the Convention was

the further election of officers.

Mr. Whipple nominated Thomas M. Kinnard for President. In a speech of

some length, Mr. Kinnard declined.

Mr. Anderson nominated J. W. Loguen for the same office. The

nomination was afterwards withdrawn, Mr. Loguen not being present, and

it being announced that he would not serve if elected.

Mr. Brown then moved to postpone the election of President for the

present. Carried.

The Convention then went into the election of members of Congress.

Messrs. A. M. Ellsworth and Osborn Anderson were elected.

After which, the Convention went into the election of Secretary of

State, to which office Richard Realf was chosen.

Whereupon the Convention adjourned to half-past two, P. M.

2 1-2, P. M. Convention again assembled, and went into a balloting for

the election of Treasurer and Secretary of the Treasury. Owen Brown

was elected as the former, and George B. Gill as the latter.

The following resolution was then introduced by Mr. Brown, and

unanimously passed:--

_Resolved_, That John Brown, J. H. Kagi, Richard Realf, L. F. Parsons,

C. P. Todd, C. Whipple, C. W. Moffit, John E. Cook, Owen Brown,

Stewart Taylor, Osborn Anderson, A. M. Ellsworth, Richard Richardson,

W. H. Leeman and John Lawrence be and are hereby appointed a Committee

to whom is delegated the power of the Convention to fill by election

all the offices specially named in the Provisional Constitution which

may be vacant after the adjournment of this Convention.

The Convention then adjourned, _sine die_.

J. H. KAGI, _Secretary of the Convention_.

NAMES OF MEMBERS OF THE CONVENTION, WRITTEN BY EACH PERSON.

William Charles Munroe, President of the Convention; G. J. Reynolds,

J. C. Grant, A. J. Smith, James M. Jones, George B. Gill, M. F.

Bailey, William Lambert, S. Hunton, C. W. Moffit, John J. Jackson,

J. Anderson, Alfred Whipple, James M. Buel, W. H. Leeman, Alfred M.

Ellsworth, John E. Cook, Stewart Taylor, James W. Purnell, George

Aiken, Stephen Dettin, Thomas Hickerson, John Caunel, Robinson

Alexander, Richard Realf, Thomas F. Cary, Richard Richardson, L. F.

Parsons, Thomas M. Kinnard, M. H. Delany, Robert Vanvanken, Thomas M,

Stringer, Charles P. Tidd, John A. Thomas, C. Whipple, I. D. Shadd,

Robert Newman, Owen Brown, John Brown, J. H. Harris, Charles Smith,

Simon Fislin, Isaac Holler, James Smith, J. H. Kagi, Secretary of the

Convention.

CHAPTER III.

THE WORK GOING BRAVELY ON--THOSE COMMISSIONS--JOHN H. KAGI--A LITTLE

CLOUD--“JUDAS” FORBES--ETC.

Many affect to despise the Chatham Convention, and the persons who

there abetted the “treason.” Governor Wise would like nothing better

than to engage the Canadas, with but ten men under his command. By that

it is clear that the men acquainted with Brown’s plans would not be a

“breakfast-spell” for the chivalrous Virginian. In one respect, they

were not formidable, and their Constitution would seem to be a harmless

paper. Some of them were outlaws against Buchanan Democratic rule

in the Territories; some were colored men who had felt severely the

proscriptive spirit of American caste; others were escaped slaves, who

had left dear kindred behind, writhing in the bloody grasp of the vile

man-stealer, never, never to be released, until some practical, daring,

determined step should be taken by their friends or their escaped

brethren. What use could such men make of a Constitution? Destitute

of political or social power, as respects the American States and

people, what ghost of an echo could they invoke, by declamation or

action, against the peculiar institution? In the light of slaveholding

logic and its conclusions, they were but renegade whites and insolent

blacks; but, aggregating their grievances, summing up their deep-seated

hostility to a system to which every precept of morality, every tie of

relationship, is a perpetual protest, the men in Convention, and the

many who could not conveniently attend at the time, were not a handful

to be despised. The braggadocio of the Virginia Governor might be eager

to engage them with ten slaveholders, but John Brown was satisfied with

them, and that is honor enough for a generation.

After the Convention adjourned, other business was despatched with

utmost speed, and every one seemed in good spirits. The “boys” of

the party of “Surveyors,” as they were called, were the admired of

those who knew them, and the subject of curious remark and inquiry

by strangers. So many intellectual looking men are seldom seen in

one party, and at the same time, such utter disregard of prevailing

custom, or style, in dress and other little conventionalities. Hour

after hour they would sit in council, thoughtful, ready; some of them

eloquent, all fearless, patient of the fatigues of business; anon, here

and there over the “track,” and again in the assembly; when the time

for relaxation came, sallying forth arm in arm, unshaven, unshorn, and

altogether indifferent about it; or one, it may be, impressed with the

coming responsibility, sauntering alone, in earnest thought, apparently

indifferent to all outward objects, but ready at a word or sign from

the chief to undertake any task.

During the sojourn at Chatham, the commissions to the men were

discussed, &c. It has been a matter of inquiry, even among friends, why

colored men were not commissioned by John Brown to act as captains,

lieutenants, &c. I reply, with the knowledge that men in the movement

now living will confirm it, that John Brown did offer the captaincy,

and other military positions, to colored men equally with others, but a

want of acquaintance with military tactics was the invariable excuse.

Holding a civil position, as we termed it, I declined a captain’s

commission tendered by the brave old man, as better suited to those

more experienced; and as I was willing to give my life to the cause,

trusting to experience and fidelity to make me more worthy, my excuse

was accepted. The same must be said of other colored men to be spoken

of hereafter, and who proved their worthiness by their able defence of

freedom at the Ferry.

JOHN H. KAGI.

Of the constellation of noble men who came to Chatham with Capt. Brown,

no one was greater in the essentials of true nobility of character and

executive skill than John H. Kagi, the confidential friend and adviser

of the old man, and second in position in the expedition; no one was

held in more deserved respect. Kagi was, singularly enough, a Virginian

by birth, and had relatives in the region of the Ferry. He left home

when a youth, an enemy to slavery, and brought as his gift offering to

freedom three slaves, whom he piloted to the North. His innate hatred

of the institution made him a willing exile from the State of his

birth, and his great abilities, natural and acquired, entitled him to

the position he held in Capt. Brown’s confidence.

Kagi was indifferent to personal appearance; he often went about

with slouched hat, one leg of his pantaloons properly adjusted, and

the other partly tucked into his high boot-top; unbrushed, unshaven,

and in utter disregard of “the latest style”; but to his companions

and acquaintances, a verification of Burns’ man in the clothes; for

John Henry Kagi had improved his time; he discoursed elegantly and

fluently, wrote ably, and could occupy the platform with greater

ability than many a man known to the American people as famous in these

respects. John Brown appreciated him, and to his men, his estimate of

John Henry was a familiar theme.

Kagi’s bravery, his devotion to the cause, his deference to the

commands of his leader, were most nobly illustrated in his conduct at

Harper’s Ferry.

* * * * *

Scarcely had the Convention and other meetings and business at Chatham

been concluded, and most necessary work been done, both at St.

Catherines and at this point, when the startling intelligence that the

plans were exposed came to hand, and that “Judas” Forbes, after having

disclosed some of our important arrangements in the Middle States,

was on his way to Washington on a similar errand. This news caused an

entire change in the programme for a time. The old gentleman went one

way, the young men another, but ultimately to meet in Kansas, in part,

where the summer was spent. In the winter of that year, Capt. Brown, J.

H. Kagi, A. D. Stevens, C. P. Tidd and Owen Brown, went into Missouri,

and released a company of slaves, whom they eventually escorted to

Canada, where they are now living and taking care of themselves. An

incident of that slave rescue may serve to illustrate more fully the

spirit pervading the old man and his “boys.” After leaving Missouri

with the fugitives, and while yet pursuing the perilous hegira, birth

was given to a male child by one of the slave mothers. Dr. Doy, of

Kansas, aided in the accouchement, and walked five miles afterwards to

get new milk for the boy, while the old Captain named him John Brown,

after himself, which name he now bears. At that time, a reward from the

United States government was upon the head of Brown; United States

Marshals were whisking about, pretendedly eager to arrest them; the

weather was very cold, and dangers were upon every hand; but not one

jot of comfort or attention for the tender babe and its invalid mother

was abated. No thought for their valuable selves, but only how best

might the poor and despised charge in their keeping be prudently but

really nursed and guarded in their trial journey for liberty. Noble

leader of a noble company of men! Yes, reader, whether at Harper’s

Ferry, or paving the way thither with such deeds as the one here told,

and well known West, the old hero and that company were philanthropists

to the core. I do not know if the wicked scheme of Forbes may not be

excused a little, solely because it afforded the occasion for the

great enterprise, growing out of this last visit to Kansas; but Forbes

himself must nevertheless be held guilty for its inception, as only

ambition to usurp power, and his great love of pelf, (peculiar to

him, of all connected with Capt. Brown,) made him dissatisfied, and

determined to add falsehood to his other sins against John Brown.

“JUDAS” FORBES.

This Forbes, who, though pretending to disclose some dangerous

hornet’s nest, was careful enough of his worthless self to tell next

to nothing, but to resort to lies, rather from a clear understanding

of the consequences, if caught, is an Englishman. When information

came, it was not known how much he had told or how little; therefore

Brown’s precaution to proceed West. From the spring of ’58 to the

autumn of ’59, getting no intelligence of him, it was said he had left

America; but instead of that, he lurked around in disguise, feeling, no

doubt, that he deserved the punishment of death. Before his defection,

he entered into agreement with Capt. Brown to work in the cause of

emancipation upon the same terms as did the others, as I repeatedly

learned from Brown and his associates, who were acquainted with the

matter, and whose veracity stands infinitely above Forbes’ word. From

Brown, Kagi and Stevens, I learned that the position of second in the

organization under the Captain was to be held by “Judas,” because of

his acquaintance with military science. He was to be drill-master

of the company, but not to receive one particle of salary more than

the youngest man in the company. But having once gained a secure

foothold, he sought to carry out his evil design to make money out of

philanthropy, or destroy the movement for ever, could he not be well

paid to remain quiet. Money was his object from the first, though

disguised; and when he failed to secure that, he raised the question of

leadership with Capt. Brown, and that was his excuse for withdrawing

from the movement. His heart was clearly never right; but he only

delayed, he did not stop the work. When the outbreak occurred, he

figured for a little while, though very cautiously, and finally fled to

Europe, another Cain, whose mark is unmistakable, and who had better

never been born than attempt to stand up among the men he so greatly

wronged.

CHAPTER IV.

THE WAY CLEAR--ACTIVE PREPARATIONS--KENNEDY FARM--EMIGRANTS FOR THE

SOUTH--CORRESPONDENCE--THE AGENT.

Throughout the summer of 1859, when every thing wore the appearance of

perfect quiet, when suspicions were all lulled, when those not fully

initiated thought the whole scheme was abandoned, arrangements were in

active preparation for the work. Mr. Brown, Kagi, and a part of the

Harper’s Ferry company, who had previously spent some time in Ohio,

went into Pennsylvania in the month of June, and up to the early

part of July, having made necessary observations, they penetrated the

Keystone yet further, and laid plans to receive freight and men as they

should arrive. Under the assumed name of Smith, Captain Brown pushed

his explorations further south, and selected

KENNEDY FARM.

Kennedy Farm, in every respect an excellent location for _business_ as

“head-quarters,” was rented at a cheap rate, and men and freight were

sent thither. Capt. Brown returned to ----, and sent freight, while

Kagi was stationed at ----, to correspond with persons elsewhere, and

to receive and despatch freight as it came. Owen, Watson, and Oliver

Brown, took their position at head-quarters, to receive whatever

was sent. These completed the arrangements. The Captain labored and

travelled night and day, sometimes on old Dolly, his brown mule, and

sometimes in the wagon. He would start directly after night, and travel

the fifty miles between the Farm and Chambersburg by daylight next

morning; and he otherwise kept open communication between head-quarters

and the latter place, in order that matters might be arranged in due

season.

John H. Kagi wrote for freight, and the following letter, before

published in relation to it, was written by a co-laborer:

WEST ANDOVER, Ohio, July 30th, 1859.

JOHN HENRIE, Esq.:

DEAR SIR,--I yesterday received yours of the 25th inst., together with

letter of instructions from our mutual friend Isaac, enclosing draft

for $100. Have written you as many as three letters, I think, before

this, and have received all you have sent, probably.

The heavy freight of fifteen boxes I sent off some days ago. The

household stuff, consisting of six boxes and one chest, I have put in

good shape, and shall, I think, be able to get them on their way on

Monday next, and shall myself be on my way northward within a day or

two after.

Enclosed please find list of contents of boxes, which it may be well

to preserve.

The freight having arrived in good condition, John Henrie replies.

As the Kennedy Farm is a part of history, a slight allusion to its

location may not be out of place, although it has been so frequently

spoken of as to be almost universally known. The Farm is located in

Washington County, Maryland, in a mountainous region, on the road from

Chambersburg; it is in a comparatively non-slaveholding population,

four miles from Harper’s Ferry. Yet, among the few traders in the

souls of men located around, several circumstances peculiar to the

institution happened while the party sojourned there, which serve to

show up its hideous character. During three weeks of my residence

at the Farm, no less than four deaths took place among the slaves;

one, Jerry, living three miles away, hung himself in the late Dr.

Kennedy’s orchard, because he was to be sold South, his master having

become insolvent. The other three cases were homicides; they were

punished so that death ensued immediately, or in a short time. It was

the knowledge of these atrocities, and the melancholy suicide named,

that caused Oliver Brown, when writing to his young wife, to refer

directly to the deplorable aspect of slavery in that neighborhood. Once

fairly established, and freight having arrived safely, the published

correspondence becomes significant to an actor in the scene. Emigrants

began to drop down, from this quarter and the other. Smith writes to

Kagi:--

WEST ANDOVER, Ashtabula Co., O., Wednesday, 1859.

FRIEND HENRIE,--Yours of the 14th inst. I received last night--glad to

learn that the “Wire” has arrived in good condition, and that our “R”

friend was pleased with a view of those “pre-eventful shadows.”

Shall write Leary at once, also our other friends at the North and

East. Am highly pleased with the prospect I have of doing something

to the purpose now, right away, here and in contiguous sections,

in the way of getting stock taken. I am devoting my whole time to

our work. Write often, and keep me posted up close. [Here follow

some phonographic characters, which may be read: “I have learned

phonography, but not enough to correspond to any advantage. Can

probably read any thing you may write, if written in the corresponding

style.”]

Faithfully yours,

JOHN SMITH.

Please say to father to address [phonographic characters which might

read “John Luther”] when he writes me. I wish you to see what I have

written him.

J. S.

THE AGENT.

In the month of August, 1859, John Brown’s Agent spent some time in

Canada. He visited Chatham, Buxton, and other places, and formed

Liberty Leagues, and arranged matters so that operations could be

carried on with excellent success, through the efficiency of Messrs.

C., S., B., and L., the Chairman, Corresponding Secretary, Secretary

O., and Treasurer of the Society. He then proceeded to Detroit, where

another Society is established. So well satisfied was Captain Brown

with the work done, that he wrote in different directions: “The fields

whiten unto harvest;” and again, “Your friends at head-quarters want

you at their elbow.” This was an invitation by the good old man to

as brave and efficient a laborer in the cause of human rights as the

friends of freedom have ever known; and to one who must yet bear the

beacon-light of liberty before the self-emancipated bondmen of the

South.

CHAPTER V.

MORE CORRESPONDENCE--MY JOURNEY TO THE FERRY--A GLANCE AT THE FAMILY.

Preparations had so far progressed, up to the time when incidents

mentioned in the preceding chapter had taken place, that Kagi wrote to

Chatham and other places, urging parties favorable to come on without

loss of time. In reply to the letter written to Chatham, soliciting

volunteers, the appended, from an office-bearer, referred to my own

journey to the South:--

DEAR SIR,--Yours came to hand last night. One hand (Anderson) left

here last night, and will be found an efficient hand. Richardson is

anxious to be at work as a missionary to bring sinners to repentance.

He will start in a few days. Another will follow immediately after, if

not with him. More laborers may be looked for shortly. “Slow but sure.”

Alexander has received yours, so you see all communications have come

to hand, so far. Alexander is not coming up to the work as he agreed.

I fear he will be found unreliable in the end.

Dull times affect missionary matters here more than any thing else;

however, a few active laborers may be looked for as certain.

I would like to hear of your congregation numbering more than “15 and

2” to commence a good revival; still, our few will be adding strength

to the good work.

Yours, &c.,

J. M. B.

To J. B., Jr.

As set forth in this letter, I left Canada September 13th, and reached

----, in Pennsylvania, three days after. On my arrival, I was surprised

to learn that the freight was all moved to head-quarters, but a few

boxes, the arrival of which, the evening of the same day, called forth

from Kagi the following brief note:--

CHAMBERSBURG, ----, ----

J. SMITH & SONS,--A quantity of freight has to-day arrived for you

in care of Oaks & Caufman. The amount is somewhere between 2,600 and

3,000 lbs. Charges in full, $25.98. The character is, according to

manifest, 33 bundles and 4 boxes.

I yesterday received a letter from John Smith, containing nothing of

any particular importance, however, so I will keep it until you come

up.

Respectfully,

J. HENRIE.

CHAMBERSBURG, Pa., Friday, Sept. 16, 1859, }

11 o’clock, A. M. }

J. SMITH AND SONS,--I have just time to say that Mr. Anderson arrived

in the train five minutes ago.

Respectfully,

J. HENRIE.

P. S. I have not had time to talk with him.

J. H.

A little while prior to this, * * went down to ----, to accompany

Shields Green, whereupon a meeting of Capt. Brown, Kagi, and other

distinguished persons, convened for consultation.

On the 20th, four days after I reached this outpost, Capt. Brown,

Watson Brown, Kagi, myself, and several friends, held another meeting,

after which, on the 24th, I left Chambersburg for Kennedy Farm. I

walked alone as far as Middletown, a town on the line between Maryland

and Pennsylvania, and it being then dark, I found Captain Brown

awaiting with his wagon. We set out directly, and drove until nearly

day-break the next morning, when we reached the Farm in safety. As a

very necessary precaution against surprise, all the colored men at the

Ferry who went from the North, made the journey from the Pennsylvania

line in the night. I found all the men concerned in the undertaking

on hand when I arrived, excepting Copeland, Leary, and Merriam; and

when all had collected, a more earnest, fearless, determined company

of men it would be difficult to get together. There, as at Chatham, I

saw the same evidence of strong and commanding intellect, high-toned

morality, and inflexibility of purpose in the men, and a profound and

holy reverence for God, united to the most comprehensive, practical,

systematic philanthropy, and undoubted bravery in the patriarch

leader, brought out to view in lofty grandeur by the associations

and surroundings of the place and the occasion. There was no milk

and water sentimentality--no offensive contempt for the negro, while

working in his cause; the pulsations of each and every heart beat in

harmony for the suffering and pleading slave. I thank God that I have

been permitted to realize to its furthest, fullest extent, the moral,

mental, physical, social harmony of an Anti-Slavery family, carrying

out to the letter the principles of its antetype, the Anti-Slavery

cause. In John Brown’s house, and in John Brown’s presence, men

from widely different parts of the continent met and united into one

company, wherein no hateful prejudice dared intrude its ugly self--no

ghost of a distinction found space to enter.

CHAPTER VI.

LIFE AT KENNEDY FARM.

To a passer-by, the house and its surroundings presented but

indifferent attractions. Any log tenement of equal dimensions would

be as likely to arrest a stray glance. Rough, unsightly, and aged, it

was only those privileged to enter and tarry for a long time, and to

penetrate the mysteries of the two rooms it contained--kitchen, parlor,

dining-room below, and the spacious chamber, attic, store-room, prison,

drilling room, comprised in the loft above--who could tell how we lived

at Kennedy Farm.

Every morning, when the noble old man was at home, he called the

family around, read from his Bible, and offered to God most fervent

and touching supplications for all flesh; and especially pathetic were

his petitions in behalf of the oppressed. I never heard John Brown

pray, that he did not make strong appeals to God for the deliverance of

the slave. This duty over, the men went to the loft, there to remain

all the day long; few only could be seen about, as the neighbors were

watchful and suspicious. It was also important to talk but little

among ourselves, as visitors to the house might be curious. Besides

the daughter and daughter-in-law, who superintended the work, some one

or other of the men was regularly detailed to assist in the cooking,

washing, and other domestic work. After the ladies left, we did all the

work, no one being exempt, because of age or official grade in the

organization.

The principal employment of the prisoners, as we severally were when

compelled to stay in the loft, was to study Forbes’ Manual, and to

go through a quiet, though rigid drill, under the training of Capt.

Stevens, at some times. At others, we applied a preparation for

bronzing our gun barrels--discussed subjects of reform--related our

personal history; but when our resources became pretty well exhausted,

the _ennui_ from confinement, imposed silence, etc., would make the men

almost desperate. At such times, neither slavery nor slaveholders were

discussed mincingly. We were, while the ladies remained, often relieved

of much of the dullness growing out of restraint by their kindness.

As we could not circulate freely, they would bring in wild fruit and

flowers from the woods and fields. We were well supplied with grapes,

paw-paws, chestnuts, and other small fruit, besides bouquets of fall

flowers, through their thoughtful consideration.

During the several weeks I remained at the encampment, we were under

the restraint I write of through the day; but at night, we sallied

out for a ramble, or to breathe the fresh air and enjoy the beautiful

solitude of the mountain scenery around, by moonlight.

Captain Brown loved the fullest expression of opinion from his men,

and not seldom, when a subject was being severely scrutinized by Kagi,

Oliver, or others of the party, the old gentleman would be one of the

most interested and earnest hearers. Frequently his views were severely

criticised, when no one would be in better spirits than himself.

He often remarked that it was gratifying to see young men grapple

with moral and other important questions, and express themselves

independently; it was evidence of self-sustaining power.

CHAPTER VII.

CAPTAIN BROWN AND J. H. KAGI GO TO PHILADELPHIA--F. J. MERRIAM, J.

COPELAND AND S. LEARY ARRIVE--MATTERS PRECIPITATED BY INDISCRETION.

Being obliged, from the space I propose to give to this narrative, to

omit many incidents of my sojourn at the Farm, which from association

are among my most pleasant recollections, the events now to be recorded

are to me invested with the most intense interest. About ten days

before the capture of the Ferry, Captain John Brown and Kagi went to

Philadelphia, on business of great importance. How important, men

there and elsewhere _now_ know. How affected by, and affecting the

main features of the enterprise, we at the Farm knew full well after

their return, as the old Captain, in the fullness of his overflowing,

saddened heart, detailed point after point of interest. God bless the

old veteran, who could and did chase a thousand in life, and defied

more than ten thousand by the moral sublimity of his death!

On their way home, at Chambersburg, they met young F. J. Merriam, of

Boston. Several days were spent at C., when Merriam left for Baltimore,

to purchase some necessary articles for the undertaking. John Copeland

and Sherrard Lewis Leary reached Chambersburg on the 12th of October,

and on Saturday, the 15th, at daylight, they arrived, in company with

Kagi and Watson Brown. In the evening of the same day, F. J. Merriam

came to the Farm.

Saturday, the 15th, was a busy day for all hands. The chief and every

man worked busily, packing up, and getting ready to remove the means of

defence to the school-house, and for further security, as the people

living around were in a state of excitement, from having seen a number

of men about the premises a few days previously. Not being fully

satisfied as to the real business of “J. Smith & Sons” after that,

and learning that several thousand stand of arms were to be removed

by the Government from the Armory to some other point, threats to

search the premises were made against the encampment. A tried friend

having given information of the state of public feeling without, and

of the intended process, Captain Brown and party concluded to strike

the blow immediately, and not, as at first intended, to await certain

reinforcements from the North and East, which would have been in

Maryland within one and three weeks. Could other parties, waiting for

the word, have reached head-quarters in time for the outbreak when it

took place, the taking of the armory, engine house, and rifle factory,

would have been quite different. But the men at the Farm had been so

closely confined, that they went out about the house and farm in the

day-time during that week, and so indiscreetly exposed their numbers

to the prying neighbors, who thereupon took steps to have a search

instituted in the early part of the coming week. Capt. Brown was not

seconded in another quarter as he expected at the time of the action,

but could the fears of the neighbors have been allayed for a few days,

the disappointment in the former respect would not have had much weight.

The indiscretion alluded to has been greatly lamented by all of us,

as Maryland, Virginia, and other slave States, had, as they now have,

a direct interest in the successful issue of the first step. Few

ultimately successful movements were predicated on the issue of the

first bold stroke, and so it is with the institution of slavery. It

will yet come down by the run, but it will not be because huzzas of

victory were shouted over the first attempt, any more than at Bunker

Hill or Hastings.

CHAPTER VIII.

COUNCIL MEETINGS--ORDERS GIVEN--THE CHARGE--ETC.

On Sunday morning, October 16th, Captain Brown arose earlier than

usual, and called his men down to worship. He read a chapter from the

Bible, applicable to the condition of the slaves, and our duty as their

brethren, and then offered up a fervent prayer to God to assist in

the liberation of the bondmen in that slaveholding land. The services

were impressive beyond expression. Every man there assembled seemed to

respond from the depths of his soul, and throughout the entire day, a

deep solemnity pervaded the place. The old man’s usually weighty words

were invested with more than ordinary importance, and the countenance

of every man reflected the momentous thought that absorbed his

attention within.

After breakfast had been despatched, and the roll called by the

Captain, a sentinel was posted outside the door, to warn by signal

if any one should approach, and we listened to preparatory remarks

to a council meeting to be held that day. At 10 o’clock, the council

was assembled. I was appointed to the Chair, when matters of

importance were considered at length. After the council adjourned, the

Constitution was read for the benefit of the few who had not before

heard it, and the necessary oaths taken. Men who were to hold military

positions in the organization, and who had not received commissions

before then, had their commissions filled out by J. H. Kagi, and gave

the required obligations.

In the afternoon, the eleven orders presented in the next chapter

were given by the Captain, and were afterwards carried out in every

particular by the officers and men.

In the evening, before setting out to the Ferry, he gave his final

charge, in which he said, among other things:--“_And now, gentlemen,

let me impress this one thing upon your minds. You all know how dear

life is to you, and how dear your life is to your friends. And in

remembering that, consider that the lives of others are as dear to them

as yours are to you. Do not, therefore, take the life of any one, if

you can possibly avoid it; but if it is necessary to take life in order

to save your own, then make sure work of it._”

CHAPTER IX.

THE ELEVEN ORDERS GIVEN BY CAPTAIN BROWN TO HIS MEN BEFORE SETTING OUT

FOR THE FERRY.

The orders given by Captain Brown, before departing from the Farm for

the Ferry, were:--

1. Captain Owen Brown, F. J. Merriam, and Barclay Coppic to remain at

the old house as sentinels, to guard the arms and effects till morning,

when they would be joined by some of the men from the Ferry with teams

to move all arms and other things to the old school-house before

referred to, located about three-quarters of a mile from Harper’s

Ferry--a place selected a day or two beforehand by the Captain.

2. All hands to make as little noise as possible going to the Ferry,

so as not to attract attention till we could get to the bridge; and to

keep all arms secreted, so as not to be detected if met by any one.

3. The men were to walk in couples, at some distance apart; and should

any one overtake us, stop him and detain him until the rest of our

comrades were out of the road. The same course to be pursued if we were

met by any one.

4. That Captains Charles P. Tidd and John E. Cook walk ahead of the

wagon in which Captain Brown rode to the Ferry, to tear down the

telegraph wires on the Maryland side along the railroad; and to do the

same on the Virginia side, after the town should be captured.

5. Captains John H. Kagi and A. D. Stevens were to take the watchman

at the Ferry bridge prisoner when the party got there, and to detain

him there until the engine house upon the Government grounds should be

taken.

6. Captain Watson Brown and Stewart Taylor were to take positions at

the Potomac bridge, and hold it till morning. They were to stand on

opposite sides, a rod apart, and if any one entered the bridge, they

were to let him get in between them. In that case, pikes were to be

used, not Sharp’s rifles, unless they offered much resistance, and

refused to surrender.

7. Captains Oliver Brown and William Thompson were to execute a similar

order at the Shenandoah bridge, until morning.

8. Lieutenant Jeremiah Anderson and Adolphus Thompson were to occupy

the engine house at first, with the prisoner watchman from the bridge

and the watchman belonging to the engine-house yard, until the one on

the opposite side of the street and the rifle factory were taken, after

which they would be reinforced, to hold that place with the prisoners.

9. Lieutenant Albert Hazlett and Private Edwin Coppic were to hold the

Armory opposite the engine house after it had been taken, through the

night and until morning, when arrangements would be different.

10. That John H. Kagi, Adjutant General, and John A. Copeland,

(colored,) take positions at the rifle factory through the night, and

hold it until further orders.

11. That Colonel A. D. Stevens (the same Captain Stevens who held

military position next to Captain Brown) proceed to the country with

his men, and after taking certain parties prisoners bring them to the

Ferry. In the case of Colonel Lewis Washington, who had arms in his

hands, he must, before being secured as a prisoner, deliver them into

the hands of Osborne P. Anderson. Anderson being a colored man, and

colored men being only _things_ in the South, it is proper that the

South be taught a lesson upon this point.

John H. Kagi being Adjutant General, was the near adviser of Captain

John Brown, and second in position; and had the old gentleman been

slain at the Ferry, and Kagi been spared, the command would have

devolved upon the latter. But Col. Stevens holding the active military

position in the organization second to Captain Brown, when order eleven

was given him, had the privilege of choosing his own men to execute it.

The selection was made after the capture of the Ferry, and then my duty

to receive Colonel Washington’s famous arms was assigned me by Captain

Brown. The men selected by Col. Stevens to act under his orders during

the night were Charles P. Tidd, Osborne P. Anderson, Shields Green,

John E. Cook, and Sherrard Lewis Leary. We were to take prisoners, and

any slaves who would come, and bring them to the Ferry.

A few days before, Capt. Cook had travelled along the Charlestown

turnpike, and collected statistics of the population of slaves and the

masters’ names. Among the masters whose acquaintance Cook had made,

Colonel Washington had received him politely, and had shown him a

sword formerly owned by Frederic the Great of Prussia, and presented

by him to Genl. Washington, and a pair of horse pistols, formerly

owned by General Lafayette, and bequeathed by the old General to Lewis

Washington. These were the arms specially referred to in the charge.

At eight o’clock on Sunday evening, Captain Brown said: “Men, get on

your arms; we will proceed to the Ferry.” His horse and wagon were

brought out before the door, and some pikes, a sledge-hammer and

crowbar were placed in it. The Captain then put on his old Kansas

cap, and said: “Come, boys!” when we marched out of the camp behind

him, into the lane leading down the hill to the main road. As we

formed the procession line, Owen Brown, Barclay Coppic, and Francis J.

Merriam, sentinels left behind to protect the place as before stated,

came forward and took leave of us; after which, agreeably to previous

orders, and as they were better acquainted with the topography of the

Ferry, and to effect the tearing down of the telegraph wires, C. P.

Tidd and John E. Cook led the procession. While going to the Ferry, the

company marched along as solemnly as a funeral procession, till we got

to the bridge. When we entered, we halted, and carried out an order to

fasten our cartridge boxes outside of our clothes, when every thing was

ready for taking the town.

CHAPTER X.

THE CAPTURE OF HARPER’S FERRY--COL. A. D. STEVENS AND PARTY SALLY OUT

TO THE PLANTATIONS--WHAT WE SAW, HEARD, DID, ETC.

As John H. Kagi and A. D. Stevens entered the bridge, as ordered in the

fifth charge, the watchman, being at the other end, came toward them

with a lantern in his hand. When up to them, they told him he was their

prisoner, and detained him a few minutes, when he asked them to spare

his life. They replied, they did not intend to harm him; the object was

to free the slaves, and he would have to submit to them for a time, in

order that the purpose might be carried out.

Captain Brown now entered the bridge in his wagon, followed by the rest

of us, until we reached that part where Kagi and Stevens held their

prisoner, when he ordered Watson Brown and Stewart Taylor to take the

positions assigned them in order sixth, and the rest of us to proceed

to the engine house. We started for the engine house, taking the

prisoner along with us. When we neared the gates of the engine-house

yard, we found them locked, and the watchman on the inside. He was told

to open the gates, but refused, and commenced to cry. The men were

then ordered by Captain Brown to open the gates forcibly, which was

done, and the watchman taken prisoner. The two prisoners were left in

the custody of Jerry Anderson and Adolphus Thompson, and A. D. Stevens

arranged the men to take possession of the Armory and rifle factory.

About this time, there was apparently much excitement. People were

passing back and forth in the town, and before we could do much, we had

to take several prisoners. After the prisoners were secured, we passed

to the opposite side of the street and took the Armory, and Albert

Hazlett and Edwin Coppic were ordered to hold it for the time being.

The capture of the rifle factory was the next work to be done. When we

went there, we told the watchman who was outside of the building our

business, and asked him to go along with us, as we had come to take

possession of the town, and make use of the Armory in carrying out our

object. He obeyed the command without hesitation. John H. Kagi and John

Copeland were placed in the Armory, and the prisoners taken to the

engine house. Following the capture of the Armory, Oliver Brown and

William Thompson were ordered to take possession of the bridge leading

out of town, across the Shenandoah river, which they immediately did.

These places were all taken, and the prisoners secured, without the

snap of a gun, or any violence whatever.

The town being taken, Brown, Stevens, and the men who had no post in

charge, returned to the engine house, where council was held, after

which Captain Stevens, Tidd, Cook, Shields Green, Leary and myself

went to the country. On the road, we met some colored men, to whom we

made known our purpose, when they immediately agreed to join us. They

said they had been long waiting for an opportunity of the kind. Stevens

then asked them to go around among the colored people and circulate

the news, when each started off in a different direction. The result

was that many colored men gathered to the scene of action. The first

prisoner taken by us was Colonel Lewis Washington. When we neared

his house, Capt. Stevens placed Leary and Shields Green to guard the

approaches to the house, the one at the side, the other in front. We

then knocked, but no one answering, although females were looking from

upper windows, we entered the building and commenced a search for the

proprietor. Col. Washington opened his room door, and begged us not to

kill him. Capt. Stevens replied, “You are our prisoner,” when he stood

as if speechless or petrified. Stevens further told him to get ready to

go to the Ferry; that he had come to abolish slavery, not to take life

but in self-defence, but that he _must_ go along. The Colonel replied:

“You can have my slaves, if you will let me remain.” “No,” said the

Captain, “you must go along too; so get ready.” After saying this,

Stevens left the house for a time, and with Green, Leary and Tidd,

proceeded to the “Quarters,” giving the prisoner in charge of Cook and

myself. The male slaves were gathered together in a short time, when

horses were tackled to the Colonel’s two-horse carriage and four-horse

wagon, and both vehicles brought to the front of the house.

During this time, Washington was walking the floor, apparently much

excited. When the Captain came in, he went to the sideboard, took

out his whiskey, and offered us something to drink, but he was

refused. His fire-arms were next demanded, when he brought forth one

double-barrelled gun, one small rifle, two horse-pistols and a sword.

Nothing else was asked of him. The Colonel cried heartily when he

found he must submit, and appeared taken aback when, on delivering up

the famous sword formerly presented by Frederic to his illustrious

kinsman, George Washington, Capt. Stevens told me to step forward and

take it. Washington was secured and placed in his wagon, the women of

the family making great outcries, when the party drove forward to Mr.

John Allstadt’s. After making known our business to him, he went into

as great a fever of excitement as Washington had done. We could have

his slaves, also, if we would only leave him. This, of course, was

contrary to our plans and instructions. He hesitated, puttered around,

fumbled and meditated for a long time. At last, seeing no alternative,

he got ready, when the slaves were gathered up from about the quarters

by their own consent, and all placed in Washington’s big wagon and

returned to the Ferry.

One old colored lady, at whose house we stopped, a little way from the

town, had a good time over the message we took her. This liberating the

slaves was the very thing she had longed for, prayed for, and dreamed

about, time and again; and her heart was full of rejoicing over the

fulfilment of a prophecy which had been her faith for long years. While

we were absent from the Ferry, the train of cars for Baltimore arrived,

and was detained. A colored man named Haywood, employed upon it, went

from the Wager House up to the entrance to the bridge, where the train

stood, to assist with the baggage. He was ordered to stop by the

sentinels stationed at the bridge, which he refused to do, but turned

to go in an opposite direction, when he was fired upon, and received a

mortal wound. Had he stood when ordered, he would not have been harmed.

No one knew at the time whether he was white or colored, but his

movements were such as to justify the sentinels in shooting him, as he

would not stop when commanded. The first firing happened at that time,

and the only firing, until after daylight on Monday morning.

CHAPTER XI.

THE EVENTS OF MONDAY, OCT. 17--ARMING THE SLAVES--TERROR IN THE

SLAVEHOLDING CAMP--IMPORTANT LOSSES TO OUR PARTY--THE FATE OF

KAGI--PRISONERS ACCUMULATE--WORKMEN AT THE KENNEDY FARM--ETC.

Monday, the 17th of October, was a time of stirring and exciting

events. In consequence of the movements of the night before, we were

prepared for commotion and tumult, but certainly not for more than we

beheld around us. Gray dawn and yet brighter daylight revealed great

confusion, and as the sun arose, the panic spread like wild-fire.

Men, women and children could be seen leaving their homes in every

direction; some seeking refuge among residents, and in quarters further

away, others climbing up the hill-sides, and hurrying off in various

directions, evidently impelled by a sudden fear, which was plainly

visible in their countenances or in their movements.

Capt. Brown was all activity, though I could not help thinking that at

times he appeared somewhat puzzled. He ordered Sherrard Lewis Leary,

and four slaves, and a free man belonging in the neighborhood, to join

John Henry Kagi and John Copeland at the rifle factory, which they

immediately did. Kagi, and all except Copeland, were subsequently

killed, but not before having communicated with Capt. Brown, as will be

set forth further along.

As fast as the workmen came to the building, or persons appeared in the

street near the engine house, they were taken prisoners, and directly

after sunrise, the detained train was permitted to start for the

eastward. After the departure of the train, quietness prevailed for a

short time; a number of prisoners were already in the engine house, and

of the many colored men living in the neighborhood, who had assembled

in the town, a number were armed for the work.

Capt. Brown ordered Capts. Charles P. Tidd, Wm. H. Leeman, John E.

Cook, and some fourteen slaves, to take Washington’s four-horse

wagon, and to join the company under Capt. Owen Brown, consisting of

F. J. Merriam and Barclay Coppic, who had been left at the Farm the

night previous, to guard the place and the arms. The company, thus

reinforced, proceeded, under Owen Brown, to move the arms and goods

from the Farm down to the school-house in the mountains, three-fourths

of a mile from the Ferry.

Capt. Brown next ordered me to take the pikes out of the wagon in which

he rode to the Ferry, and to place them in the hands of the colored

men who had come with us from the plantations, and others who had come

forward without having had communication with any of our party. It was

out of the circumstances connected with the fulfilment of this order,

that the false charge against “Anderson” as leader, or “ringleader,” of

the negroes, grew.

The spectators, about this time, became apparently wild with fright

and excitement. The number of prisoners was magnified to hundreds,

and the judgment-day could not have presented more terrors, in its

awful and certain prospective punishment to the justly condemned for

the wicked deeds of a life-time, the chief of which would no doubt be

slaveholding, than did Capt. Brown’s operations.

The prisoners were also terror-stricken. Some wanted to go home to see

their families, as if for the last time. The privilege was granted

them, under escort, and they were brought back again. Edwin Coppic,

one of the sentinels at the Armory gate, was fired at by one of the

citizens, but the ball did not reach him, when one of the insurgents

close by put up his rifle, and made the enemy bite the dust.

Among the arms taken from Col. Washington was one double-barrel gun.

This weapon was loaded by Leeman with buckshot, and placed in the hands

of an elderly slave man, early in the morning. After the cowardly

charge upon Coppic, this old man was ordered by Capt. Stevens to arrest

a citizen. The old man ordered him to halt, which he refused to do,

when instantly the terrible load was discharged into him, and he fell,

and expired without a struggle.

After these incidents, time passed away till the arrival of the United

States troops, without any further attack upon us. The cowardly

Virginians submitted like sheep, without resistance, from that

time until the marines came down. Meanwhile, Capt. Brown, who was

considering a proposition for release from his prisoners, passed back

and forth from the Armory to the bridge, speaking words of comfort and

encouragement to his men. “Hold on a little longer, boys,” said he,

“until I get matters arranged with the prisoners.” This tardiness on

the part of our brave leader was sensibly felt to be an omen of evil by

some us, and was eventually the cause of our defeat. It was no part of

the original plan to hold on to the Ferry, or to parley with prisoners;

but by so doing, time was afforded to carry the news of its capture to

several points, and forces were thrown into the place, which surrounded

us.

At eleven o’clock, Capt. Brown despatched William Thompson from the

Ferry up to Kennedy Farm, with the news that we had peaceful possession

of the town, and with directions to the men to continue on moving the

things. He went; but before he could get back, troops had begun to pour

in, and the general encounter commenced.

CHAPTER XII.

RECEPTION TO THE TROOPS--THEY RETREAT TO THE BRIDGE--A PRISONER--DEATH

OF DANGERFIELD NEWBY--WILLIAM THOMPSON--THE MOUNTAINS ALIVE--FLAG OF

TRUCE--THE ENGINE HOUSE TAKEN.

It was about twelve o’clock in the day when we were first attacked by

the troops. Prior to that, Capt. Brown, in anticipation of further

trouble, had girded to his side the famous sword taken from Col.

Lewis Washington the night before, and with that memorable weapon, he

commanded his men against General Washington’s own State.

When the Captain received the news that the troops had entered the

bridge from the Maryland side, he, with some of his men, went into the

street, and sent a message to the Arsenal for us to come forth also.

We hastened to the street as ordered, when he said--“The troops are on

the bridge, coming into town; we will give them a warm reception.” He

then walked around amongst us, giving us words of encouragement, in

this wise:--“Men! be cool! Don’t waste your powder and shot! Take aim,

and make every shot count!” “The troops will look for us to retreat on

their first appearance; be careful to shoot first.” Our men were well

supplied with fire-arms, but Capt. Brown had no rifle at that time; his

only weapon was the sword before mentioned.

The troops soon came out of the bridge, and up the street facing us, we

occupying an irregular position. When they got within sixty or seventy

yards, Capt. Brown said, “Let go upon them!” which we did, when several

of them fell. Again and again the dose was repeated.

There was now consternation among the troops. From marching in solid

martial columns, they became scattered. Some hastened to seize upon

and bear up the wounded and dying,--several lay dead upon the ground.

They seemed not to realize, at first, that we would fire upon them, but

evidently expected we would be driven out by them without firing. Capt.

Brown seemed fully to understand the matter, and hence, very properly

and in our defence, undertook to forestall their movements. The

consequence of their unexpected reception was, after leaving several of

their dead on the field, they beat a confused retreat into the bridge,

and there stayed under cover until reinforcements came to the Ferry.

On the retreat of the troops, we were ordered back to our former post.

While going, Dangerfield Newby, one of our colored men, was shot

through the head by a person who took aim at him from a brick store

window, on the opposite side of the street, and who was there for the

purpose of firing upon us. Newby was a brave fellow. He was one of my

comrades at the Arsenal. He fell at my side, and his death was promptly

avenged by Shields Green, the Zouave of the band, who afterwards met

his fate calmly on the gallows, with John Copeland. Newby was shot

twice; at the first fire, he fell on his side and returned it; as he

lay, a second shot was fired, and the ball entered his head. Green

raised his rifle in an instant, and brought down the cowardly murderer,

before the latter could get his gun back through the sash.

There was comparative quiet for a time, except that the citizens seemed

to be wild with terror. Men, women and children forsook the place in

great haste, climbing up hill-sides and scaling the mountains. The

latter seemed to be alive with white fugitives, fleeing from their

doomed city. During this time, Wm. Thompson, who was returning from

his errand to the Kennedy Farm, was surrounded on the bridge by the

railroad men, who next came up, taken a prisoner to the Wager House,

tied hand and foot, and, at a late hour of the afternoon, cruelly

murdered by being riddled with balls, and thrown headlong on the rocks.

Late in the morning, some of his prisoners told Capt. Brown that they

would like to have breakfast, when he sent word forthwith to the

Wager House to that effect, and they were supplied. He did not order

breakfast for himself and men, as was currently but falsely stated at

the time, as he suspected foul play; on the contrary, when solicited to

have breakfast so provided for him, he refused.

Between two and three o’clock in the afternoon, armed men could

be seen coming from every direction; soldiers were marching and

counter-marching; and on the mountains, a host of blood-thirsty

ruffians swarmed, waiting for their opportunity to pounce upon the

little band. The fighting commenced in earnest after the arrival of

fresh troops. Volley upon volley was discharged, and the echoes from

the hills, the shrieks of the townspeople, and the groans of their

wounded and dying, all of which filled the air, were truly frightful.

The Virginians may well conceal their losses, and Southern chivalry may

hide its brazen head, for their boasted bravery was well tested that

day, and in no way to their advantage. It is remarkable, that except

that one foolhardy colored man was reported buried, no other funeral

is mentioned, although the Mayor and other citizens are known to have

fallen. Had they reported the true number, their disgrace would have

been more apparent; so they wisely (?) concluded to be silent.

The fight at Harper’s Ferry also disproved the current idea that

slaveholders will lay down their lives for their property. Col.

Washington, the representative of the old hero, stood “blubbering” like

a great calf at supposed danger; while the laboring white classes and

non-slaveholders, with the marines, (mostly gentlemen from “furrin”

parts,) were the men who faced the bullets of John Brown and his men.

Hardly the skin of a slaveholder could be scratched in open fight; the

cowards kept out of the way until danger was passed, sending the poor

whites into the pitfalls, while they were reserved for the bragging,

and to do the safe but cowardly judicial murdering afterwards.

As strangers poured in, the enemy took positions round about, so as to

prevent any escape, within shooting distance of the engine house and

Arsenal. Capt. Brown, seeing their manœuvres, said: “We will hold on to

our three positions, if they are unwilling to come to terms, and die

like men.”

All this time, the fight was progressing; no powder and ball were

wasted. We shot from under cover, and took deadly aim. For an hour

before the flag of truce was sent out, the firing was uninterrupted,

and one and another of the enemy were constantly dropping to the earth.

One of the Captain’s plans was to keep up communication between his

three points. In carrying out this idea, Jerry Anderson went to the

rifle factory, to see Kagi and his men. Kagi, fearing that we would be

overpowered by numbers if the Captain delayed leaving, sent word by

Anderson to advise him to leave the town at once. This word Anderson

communicated to the Captain, and told us also at the Arsenal. The

message sent back to Kagi was, to hold out for a few minutes longer,

when we would all evacuate the place. Those few minutes proved

disastrous, for then it was that the troops before spoken of came

pouring in, increased by crowds of men from the surrounding country.

After an hour’s hard fighting, and when the enemy were blocking up the

avenues of escape, Capt. Brown sent out his son Watson with a flag of

truce, but no respect was paid to it; he was fired upon, and wounded

severely. He returned to the engine house, and fought bravely after

that for fully an hour and a half, when he received a mortal wound,

which he struggled under until the next day. The contemptible and

savage manner in which the flag of truce had been received, induced

severe measures in our defence, in the hour and a half before the next

one was sent out. The effect of our work was, that the troops ceased to