*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 44166 ***

“If this country cannot be saved without giving up the principle of

Liberty, I was about to say I would rather be assassinated on this

spot than surrender it.”

_From Mr. Lincoln’s Speech at Independence Hall, Philadelphia,

February 21, 1861._

“I believe this Government cannot endure permanently half slave and

half free.”

_Springfield, Illinois, June, 1858._

“I am exceedingly anxious that this Union, the Constitution, and

the liberties of the people shall be perpetuated in accordance with

the original idea for which the Revolution was made.”

_Trenton, New Jersey, February 21, 1861._

“Having thus chosen our course, without guile and with pure

purpose, let us renew our trust in God, and go forward without fear

and with manly hearts.”

_Message, July 5, 1861._

“In giving freedom to the slaves, we assure freedom to the free;

honorable alike in what we give and what we preserve.”

_Message, December 1, 1862._

“I hope peace will come soon, and come to stay; and so come as to

be worth the keeping in all future time.”

_Springfield Letter, August 26, 1863._

“The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here;

but it can never forget what the brave men, living and dead, did

here.”

_Speech at Gettysburg, November 19, 1863._

“I shall not attempt to retract or modify the Emancipation

Proclamation, nor shall I return to slavery any person who is

free by the terms of that proclamation, or by any of the Acts of

Congress.”

_Amnesty Proclamation, December 8, 1863._

“I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that

events have controlled me.”

_Letter to A. G. Hodges, April 4, 1864._

“With malice towards none, with charity for all, with firmness in

the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to

finish the work we are in.”

_Last Inaugural, March 4, 1865._

[Illustration]

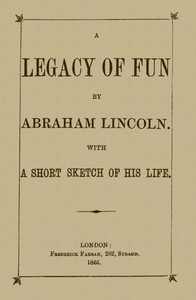

LIFE OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN,

SIXTEENTH PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES.

CONTAINING

HIS EARLY HISTORY AND POLITICAL CAREER; TOGETHER

WITH THE SPEECHES, MESSAGES, PROCLAMATIONS AND

OTHER OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS ILLUSTRATIVE OF

HIS EVENTFUL ADMINISTRATION.

BY FRANK CROSBY,

MEMBER OF THE PHILADELPHIA BAR.

“LET ALL THE ENDS THOU AIM’ST AT BE THY COUNTRY’S,

THY GOD’S AND TRUTH’S; THEN IF THOU FALL’ST

THOU FALL’ST A BLESSED MARTYR.”

NEW YORK

INTERNATIONAL BOOK COMPANY

310-318 SIXTH AVENUE

DEDICATED

TO THE GOOD AND TRUE

OF THE NATION

REDEEMED--REGENERATED--DISENTHRALLED.

PREFACE.

An attempt has been made in the following pages to portray Abraham

Lincoln, mainly in his relations to the country at large during his

eventful administration.

With this view, it has not been deemed necessary to cumber the work

with the minute details of his life prior to that time. This period

has, therefore, been but glanced at, with a care to present enough to

make a connected whole. His Congressional career and his campaign with

Senator Douglas are presented in outline, yet so, it is believed, that

a clear idea of these incidents in his life can be obtained.

After the time of his election as President, however, a different

course of treatment has been pursued. Thenceforward, to the close of

his life, especial pains have been taken to present everything which

should show him as he was--the Statesman persistent, resolute, free

from boasting or ostentation, destitute of hate, never exultant,

guarded in his prophecies, threatening none at home or abroad,

indulging in no utopian dreams of a blissful future, moving quietly,

calmly, conscientiously, irresistibly on to the end he saw with

clearest vision.

Yet, even in what is presented as a complete record of his

administration, too much must not be expected. It is impossible, for

example, to thoroughly dissect the events of the great Rebellion in

a work like the present. Nothing of the kind has been attempted. The

prominent features only have been sketched; and that solely for the

purpose of bringing into the distinct foreground him whose life is

under consideration.

Various Speeches, Proclamations, and Letters, not vitally essential

to the unity of the main body of the work, yet valuable as affording

illustrations of the man--have been collected in the Appendix.

Imperfect as this portraiture must necessarily be, there is one

conciliatory thought. The subject needs no embellishment. It furnishes

its own setting. The acts of the man speak for themselves. Only such an

arrangement is needed as shall show the bearing of each upon the other,

the development of each, the processes of growth.

Those words of the lamented dead which nestle in our hearts so

tenderly--they call for no explanation. Potent, searching, taking hold

of our consciences, they will remain with us while reason lasts.

Nor will the people’s interest be but for the moment. The baptism of

blood to which the Nation has been called, cannot be forgotten for

generations. And while memories of him abide, there will inevitably be

associated with them the placid, quiet face, not devoid of mirth--its

patient, anxious, yet withal hopeful expression--the sure, elastic

step--the clearly cut, sharply defined speech of him, who, under

Providence, was to lead us through the trial and anguish of those

bitter days to the rest and refreshing of a peace, whose dawn only,

alas! he was to see.

Though this work may not rise to the height required, it is hoped that

it is not utterly unworthy of the subject. Such as it is--a labor of

love--it is offered to those who loved and labored with the patriot

and hero, with the earnest desire that it may not be regarded an

unwarrantable intrusion upon ground on which any might hesitate to

venture.

F. C.

_Philadelphia, June, 1865._

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I.

BOYHOOD AND EARLY MANHOOD.

Preliminary--Birth of Abraham Lincoln--Removal from Kentucky--At

Work--Self Education--Personal Characteristics--Another Removal

--Trip to New Orleans--Becomes Clerk--Black Hawk War--Engages in

Politics--Successive Elections to the Legislature--Anti-Slavery

Protest--Commences Practice as a Lawyer--Traits of Character--

Marriage--Return to Politics--Election to Congress 13

CHAPTER II.

IN CONGRESS AND ON THE STUMP.

The Mexican War--Internal Improvements--Slavery in the

District of Columbia--Public Lands--Retires to Private Life--

Kansas-Nebraska Bill--Withdraws in Favor of Senator Trumbull--

Formation of Republican Party--Nominated for U. S. Senator--

Opening Speech of Mr. Lincoln--Douglas Campaign--The Canvass--

Tribute to the Declaration of Independence--Result of the Contest 19

CHAPTER III.

BEFORE THE NATION.

Speeches in Ohio--Extract from the Cincinnati Speech--Visits

the East--Celebrated Speech at the Cooper Institute, New

York--Interesting Incident 34

CHAPTER IV.

NOMINATED AND ELECTED PRESIDENT.

The Republican National Convention--Democratic Convention--

Constitutional Union Convention--Ballotings at Chicago--

The Result--Enthusiastic Reception--Visit to Springfield--

Address and Letter of Acceptance--The Campaign--Result

of the Election--South Carolina’s Movements--Buchanan’s

Pusillanimity--Secession of States--Confederate Constitution--

Peace Convention--Constitutional Amendments--Terms of the Rebels 60

CHAPTER V.

TO WASHINGTON.

The Departure--Farewell Remarks--Speech at Toledo--At

Indianapolis--At Cincinnati--At Columbus--At Steubenville--

At Pittsburgh--At Cleveland--At Buffalo--At Albany--At

Poughkeepsie--At New York--At Trenton--At Philadelphia--At

“Independence Hall”--Flag Raising--Speech at Harrisburg--

Secret Departure for Washington--Comments 67

CHAPTER VI.

THE NEW ADMINISTRATION.

Speeches at Washington--The Inaugural Address--Its Effect--

The Cabinet--Commissioners from Montgomery--Extracts from A.

H. Stephens’ Speech--Virginia Commissioners--Fall of Fort

Sumter 90

CHAPTER VII.

PREPARING FOR WAR.

Effects of Sumter’s Fall--President’s Call for Troops--

Response in the Loyal States--In the Border States--Baltimore

Riots--Maryland’s Position--President’s Letter to Maryland

Authorities--Blockade Proclamation--Additional Proclamation--

Comments Abroad--Second Call for Troops--Special Order for

Florida--Military Movements 108

CHAPTER VIII.

THE FIRST SESSION OF CONGRESS.

Opening of Congress--President’s First Message--Its Nature--

Action of Congress--Resolution Declaring the Object of the

War--Bull Run--Its Effect 117

CHAPTER IX.

CLOSE OF 1861.

Election of the Rebels--Davis’ Boast--McClellan appointed

Commander of Potomac Army--Proclamation of a National Fast--

Intercourse with Rebels Forbidden--Fugitive Slaves--Gen.

Butler’s Views--Gen. McClellan’s Letter from Secretary

Cameron--Act of August 6th, 1861--Gen. Fremont’s Order--

Letter of the President Modifying the Same--Instructions to

Gen. Sherman--Ball’s Bluff--Gen. Scott’s Retirement--Army of

the Potomac 137

CHAPTER X.

THE CONGRESS OF 1861-62.

The Military Situation--Seizure of Mason and Slidell--

Opposition to the Administration--President’s Message--

Financial Legislation--Committee on the Conduct of the War--

Confiscation Bill 148

CHAPTER XI.

THE SLAVERY QUESTION.

Situation of the President--His Policy--Gradual Emancipation--

Message--Abolition of Slavery in the District of Columbia--

Repudiation of Gen. Hunter’s Emancipation Order--Conference with

Congressmen from the Border Slave States--Address to the Same--

Military Order--Proclamation under the Conscription Act 171

CHAPTER XII.

THE PENINSULAR CAMPAIGN.

President’s War Order--Reason for the Same--Results in West

and South-west--Army of the Potomac--Presidential Orders--

Letter to McClellan--Order for Army Corps--The Issue of the

Campaign--Unfortunate Circumstances--President’s Speech

at Union Meeting--Comments--Operations in Virginia and

Maryland--In the West and South-west 181

CHAPTER XIII.

FREEDOM TO MILLIONS.

Tribune Editorial--Letter to Mr. Greeley--Announcement of the

Emancipation Proclamation--Suspension of the _Habeas Corpus_

in certain Cases--Order for Observance of the Sabbath--The

Emancipation Proclamation 190

CHAPTER XIV.

LAST SESSION OF THE THIRTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS.

Situation of the Country--Opposition to the Administration--

President’s Message 199

CHAPTER XV.

THE TIDE TURNED.

Military Successes--Favorable Elections--Emancipation Policy--

Letter to Manchester (Eng.) Workingmen--Proclamation for a

National Fast--Letter to Erastus Corning--Letter to a Committee

on Recalling Vallandigham 226

CHAPTER XVI.

LETTERS AND SPEECHES.

Speech at Washington--Letter to Gen. Grant--Thanksgiving

Proclamation--Letter Concerning the Emancipation Proclamation--

Proclamation for Annual Thanksgiving--Dedicatory Speech at

Gettysburg 242

CHAPTER XVII.

THE THIRTY-EIGHTH CONGRESS.

Organization of the House--Different Opinions as to

Reconstruction--Provisions for Pardon of Rebels--President’s

Proclamation of Pardon--Annual Message--Explanatory

Proclamation 263

CHAPTER XVIII.

PROGRESS.

President’s Speech at Washington--Speech to a New York

Committee--Speech in Baltimore--Letter to a Kentuckian--

Employment of Colored Troops--Davis’ Threat--General Order--

President’s Order on the Subject 275

CHAPTER XIX.

RENOMINATED.

Lieut. Gen. Grant--His Military Record--Continued Movements--

Correspondence with the President--Across the Rapidan--

Richmond Invested--President’s Letter to a Grant Meeting--

Meeting of Republican National Convention--The Platform--

The Nomination--Mr. Lincoln’s Reply to the Committee of

Notification--Remarks to Union League Committee--Speech at a

Serenade--Speech to Ohio Troops 285

CHAPTER XX.

RECONSTRUCTION.

President’s Speech at Philadelphia--Philadelphia Fair--

Correspondence with Committee of National Convention--

Proclamation of Martial Law in Kentucky--Question of

Reconstruction--President’s Proclamation on the Subject--

Congressional Plan 298

CHAPTER XXI.

PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN OF 1864.

Proclamation for a Fast--Speech to Soldiers--Another Speech--

“To Whom it may Concern”--Chicago Convention--Opposition

Embarrassed--Resolution No. 2--McClellan’s Acceptance--

Capture of the Mobile Forts and Atlanta--Proclamation for

Thanksgiving--Remarks on Employment of Negro Soldiers--

Address to Loyal Marylanders 314

CHAPTER XXII.

RE-ELECTED

Presidential Campaign of 1864--Fremont’s Withdrawal--Wade

and Davis--Peace and War Democrats--Rebel Sympathizers--

October Election--Result of Presidential Election--Speech to

Pennsylvanians--Speech at a Serenade--Letter to a Soldier’s

Mother--Opening of Congress--Last Annual Message 325

CHAPTER XXIII.

TIGHTENING THE LINES.

Speech at a Serenade--Reply to a Presentation Address--Peace

Rumors--Rebel Commissioners--Instructions to Secretary

Seward--The Conference in Hampton Roads--Result--Extra

Session of the Senate--Military Situation--Sherman--

Charleston--Columbia--Wilmington--Fort Fisher--Sheridan--

Grant--Rebel Congress--Second Inauguration--Inaugural--

English Comment--Proclamation to Deserters 350

CHAPTER XXIV.

IN RICHMOND.

President Visits City Point--Lee’s Failure--Grant’s Movement--

Abraham Lincoln in Richmond--Lee’s Surrender--President’s

Impromptu Speech--Speech on Reconstruction--Proclamation Closing

Certain Ports--Proclamation Relative to Maritime Rights--

Supplementary Proclamation--Orders from the War Department--

The Traitor President 362

CHAPTER XXV.

THE LAST ACT.

Interview with Mr. Colfax--Cabinet Meeting--Incident--

Evening Conversation--Possibility of Assassination--Leaves

for the Theatre--In the Theatre--Precautions for the

Murder--The Pistol Shot--Escape of the Assassin--Death of

the President--Pledges Redeemed--Situation of the Country--

Effect of the Murder--Obsequies at Washington--Borne Home--

Grief of the People--At Rest 374

CHAPTER XXVI.

THE MAN.

Reasons for His Re-election--What was Accomplished--Leaning on

the People--State Papers--His Tenacity of Purpose--Washington

and Lincoln--As a Man--Favorite Poem--Autobiography--His Modesty

--A Christian--Conclusion 382

APPENDIX.

Mr. Lincoln’s Speeches in Congress and Elsewhere, Proclamations,

Letters, etc., not included in the Body of the Work.

Speech on the Mexican War, (In Congress, Jan. 12, 1848) 391

Speech on Internal Improvements, (In Congress, June 20, 1848)

403

Speech on the Presidency and General Politics, (In Congress,

July 27, 1848) 417

Speech in Reply to Mr. Douglas, on Kansas, the Dred Scott

Decision, and the Utah Question, (At Springfield, June 26,

1857) 431

Speech in Reply to Senator Douglas, (At Chicago, July 10, 1858) 442

Opening Passages of his Speech at Freeport 459

Letter to Gen. McClellan 464

Letter to Gen. Schofield Relative to the Removal of Gen. Curtis 466

Three Hundred Thousand Men Called For 466

Rev. Dr. McPheeters--President’s Reply to an Appeal for

Interference 468

An Election Ordered in the State of Arkansas 470

Letter to William Fishback on the Election in Arkansas 471

Call for Five Hundred Thousand Men 471

Letter to Mrs. Gurney 473

The Tennessee Test Oath 474

LIFE OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

CHAPTER I.

BOYHOOD AND EARLY MANHOOD.

Preliminary--Birth of Abraham Lincoln--Removal from Kentucky--

At Work--Self Education--Personal Characteristics--Another

Removal--Trip to New Orleans--Becomes Clerk--Black Hawk War--

Engages in Politics--Successive Elections to the Legislature--

Anti-Slavery Protest--Commences Practice as a Lawyer--Traits of

Character--Marriage--Return to Politics--Election to Congress.

The leading incidents in the early life of the men who have most

decidedly influenced the destinies of our republic, present a striking

similarity. The details, indeed, differ; but the story, in outline, is

the same--“the short and simple annals of the poor.”

Of obscure parentage--accustomed to toil from their tender years--with

few facilities for the education of the school--the most struggled

on, independent, self-reliant, till by their own right hands they had

hewed their way to the positions for which their individual talents

and peculiarities stamped them as best fitted. Children of nature,

rather than of art, they have ever in their later years--amid scenes

and associations entirely dissimilar to those with which in youth and

early manhood, they were familiar--retained somewhat indicative of

their origin and training. In speech or in action--often in both--they

have smacked of their native soil. If they have lacked the grace of

the courtier, ample compensation has been afforded in the honesty of

the man. If their address was at times abrupt, it was at least frank

and unmistakable. Both friend and foe knew exactly where to find them.

Unskilled in the doublings of the mere politician or the trimmer, they

have borne themselves straight forward to the points whither their

judgment and conscience directed. Such men may have been deemed fit

subjects for the jests and sneers of more cultivated Europeans, but

they are none the less dear to us as Americans--will none the less take

their place among those whose names the good, throughout the world,

will not willingly let die.

Of this class, pre-eminently, was the statesman whose life and public

services the following pages are to exhibit.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN, Sixteenth President of the United States, son

of Thomas and Nancy Lincoln--the former a Kentuckian, the latter

a Virginian--was born February 12th, 1809, near Hodgenville, the

county-seat of what is now known as La Rue county, Kentucky. He had one

sister, two years his senior, who died, married, in early womanhood;

and his only brother, his junior by two years, died in childhood.

When nine years of age, he lost his mother, the family having, two

years previously, removed to what was then the territory of Indiana,

and settled in the southern part, near the Ohio river, about midway

between Louisville and Evansville. The thirteen years which the lad

spent here inured him to all the exposures and hardships of frontier

life. An active assistant in farm duties, he neglected no opportunity

of strengthening his mind, reading with avidity such instructive works

as he could procure--on winter evenings, oftentimes, by the light of

the blazing fire-place. As satisfaction for damage accidentally done to

a borrowed copy of Weems’ Life of Washington--the only one known to be

in the neighborhood--he pulled fodder for two days for the owner.

At twenty years of age, he had reached the height of nearly six feet

and four inches, with a comparatively slender yet uncommonly strong

muscular frame--a youthful giant among a race of giants. Morally, he

was proverbially honest, conscientious, and upright.

In 1830, his father again emigrated, halting for a year on the north

fork of the Sangamon river, Illinois, but afterwards pushing on to

Coles county, some seventy miles to the eastward, on the upper waters

of the Kaskaskia and Embarrass, where his adventurous life ended in

1851, he being in his seventy-third year. The first year in Illinois

the son spent with the father; the next he aided in constructing

a flat-boat, on which, with other hands, a successful trip to New

Orleans and back was made. This city--then the El Dorado of the Western

frontiersman--had been visited by the young man, in the same capacity,

when he was nineteen years of age.

Returning from this expedition, he acted for a year as clerk for

his former employer, who was engaged in a store and flouring mill

at New Salem, twenty miles below Springfield. While thus occupied,

tidings reached him of an Indian invasion on the western border of

the State--since known as the Black Hawk war, from an old Sac chief

of that name, who was the prominent mover in the matter. In New Salem

and vicinity, a company of volunteers was promptly raised, of which

young Lincoln was elected captain--his first promotion. The company,

however, having disbanded, he again enlisted as a private, and during

the three months’ service of this, his first short military campaign,

he faithfully discharged his duty to his country, persevering amid

peculiar hardships and against the influences of older men around him.

With characteristic humor and sarcasm, while commenting, in a

Congressional speech during the canvass of 1848, upon the efforts of

General Cass’s biographers to exalt their idol into a military hero, he

thus alluded to this episode in his life:

“By the way, Mr. Speaker, did you know I am a military hero? Yes, sir,

in the days of the Black Hawk war, I fought, bled, and came away.

Speaking of General Cass’s career, reminds me of my own. I was not

at Stillman’s defeat, but I was about as near it as Cass to Hull’s

surrender; and like him, I saw the place very soon afterward. It is

quite certain I did not break my sword, for I had none to break; but I

bent a musket pretty badly on one occasion. If Cass broke his sword,

the idea is, he broke it in desperation; I bent the musket by accident.

If General Cass went in advance of me in picking whortleberries, I

guess I surpassed him in charges upon the wild onions. If he saw any

live, fighting Indians, it was more than I did, but I had a good many

bloody struggles with the mosquitoes; and although I never fainted from

loss of blood, I can truly say I was often very hungry.

“Mr. Speaker, if I should ever conclude to doff whatever our Democratic

friends may suppose there is of black-cockade Federalism about me,

and, thereupon, they should take me up as their candidate for the

Presidency, I protest they shall not make fun of me as they have of

General Cass, by attempting to write me into a military hero.”

This bit of adventure over, Mr. Lincoln--who had determined to become a

lawyer, in common with most energetic, enterprising young men of that

period and section--embarked in politics, warmly espousing the cause

of Henry Clay, in a State at that time decidedly opposed to his great

leader, and received a gratifying evidence of his personal popularity

where he was best known, in securing an almost unanimous vote in his

own precinct in Sangamon county as a candidate for representative in

the State Legislature, although a little later in the same canvass

General Jackson, the Democratic candidate for the Presidency, led his

competitor, Clay, one hundred and fifty-five votes.

While pursuing his law studies, he engaged in land surveying as a

means of support. In 1834, not yet having been admitted to the bar--a

backwoodsman in manner, dress, and expression--tall, lank, and by no

means prepossessing--he was first elected to the Legislature of his

adopted State, being the youngest member, with a single exception.

During this session he rarely took the floor to speak, content to

play the part of an observer rather than of an actor. It was at this

period that he became acquainted with Stephen A. Douglas, then a recent

immigrant from Vermont, in connection with whom he was destined to

figure so prominently before the country.

In 1836, he was elected for a second term. During this session, he put

upon record, together with one of his colleagues, his views relative to

slavery, in the following protest, bearing date March 3d, 1837:--

“Resolutions upon the subject of domestic slavery having passed

both branches of the General Assembly, at its present session, the

undersigned hereby protest against the passage of the same.

“They believe that the institution of slavery is founded on both

injustice and bad policy; but that the promulgation of abolition

doctrines tends rather to increase than abate its evils.

“They believe that the Congress of the United States has no power,

under the Constitution, to interfere with the institution of slavery in

the different States.

“They believe that the Congress of the United States has the power,

under the Constitution, to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia;

but that the power ought not to be exercised, unless at the request of

the people of said district.”

In 1838 and 1840, he was again elected and received the vote of his

party for the speakership. First elected at twenty-five, he had

been continued so long as his inclination allowed, and until by his

kind manners, his ability, and unquestioned integrity, he had won a

position, when but a little past thirty, as the virtual leader of his

party in Illinois. His reputation as a close and logical debater had

been established; his native talent as an orator had been developed;

his earnest zeal for his party had brought around him troops of

friends; while his acknowledged goodness of heart had knit many to

him, who, upon purely political grounds, would have held themselves

aloof.

While a member of the Legislature, he had devoted himself, as best he

could--considering the necessity he was under of eking out a support

for himself, and the demands made upon his time by his political

associates--to mastering his chosen profession, and in 1836 was

admitted to practice. Securing at once a good amount of business, he

began to rise as a most effective jury advocate, who could readily

perceive, and promptly avail himself of, the turning points of a

case. A certain quaint humor, withal, which he was wont to employ

in illustration--combined with his sterling, practical sense, going

straight to the core of things--stamped him as an original. Disdaining

the tricks of the mere rhetorician, he spoke from the heart to the

heart, and was universally regarded by those with whom he came in

contact as every inch a man, in the best and broadest sense of that

term. His thoughts, his manner, his address were eminently his own.

Affecting none of the cant of the demagogue, the people trusted him,

revered him as one of the best, if not the best, among them. Their

sympathies were his--their weal his desire, their interests a common

stock with his own.

Having permanently located himself at Springfield, the seat of Sangamon

county--which ever after he called his home--he devoted himself to the

practice of his profession, and on the 4th of November, 1842, married

Mary Todd, daughter of the Hon. Robert S. Todd of Lexington, Kentucky,

a lady of accomplished manners and refined social tastes.

Although he had determined to retire from the political arena and taste

the sweets which a life with one’s own family can alone secure, his

earnest wishes were at length overruled by the as earnest demands of

that party with the success of which he firmly believed his country’s

best interests identified, and in 1844 he thoroughly canvassed his

State in behalf of Clay--afterward passing into Indiana, and daily

addressing immense gatherings until the day of election. Over the

defeat of the great Kentuckian he sorrowed as one almost without hope;

feeling it, indeed, far more keenly than his generous nature would have

done, had it been a merely personal discomfiture.

Two years later, in 1846, Mr. Lincoln was persuaded to accept the Whig

nomination for Congress in the Sangamon district, and was elected by

an unprecedently large majority. Texas had meanwhile been annexed; the

Mexican war was in progress; the Tariff of 1842 had been repealed.

With the opening of the Thirtieth Congress--December 6th, 1847--Mr.

Lincoln took his seat in the lower house of Congress, Stephen A.

Douglas also appearing for the first time as a member of the Senate.

CHAPTER II.

IN CONGRESS AND ON THE STUMP.

The Mexican War--Internal Improvements--Slavery in the

District of Columbia--Public Lands--Retires to Private Life--

Kansas-Nebraska Bill--Withdraws in favor of Senator Trumbull--

Formation of Republican Party--Nominated for U. S. Senator--

Opening Speech of Mr. Lincoln--Douglas Campaign--The Canvass--

Tribute to the Declaration of Independence--Result of the Contest.

Mr. Lincoln was early recognized as one of the foremost of the Western

men upon the floor of the House. His Congressional record is that

of a Whig of those days. Believing that Mr. Polk’s administration

had mismanaged affairs with Mexico at the outset, he, in common with

others of his party, was unwilling, while voting supplies and favoring

suitable rewards for our gallant soldiers, to be forced into an

unqualified indorsement of the war with that country from its beginning

to its close.

Accordingly, December 22d, 1847, he introduced a series of resolutions

of inquiry concerning the origin of the war, calling for definite

official information, which were laid over under the rule, and never

acted upon. Upon a test question on abandoning the war, without any

material result accomplished, he voted with the minority in favor of

laying that resolution upon the table.

In all questions bearing upon the matter of internal improvements,

he took an active interest. He took manly ground in favor of the

unrestricted right of petition, and favored a liberal policy toward the

people in disposing of the public lands. He exerted himself during the

canvass of 1848, to secure the election of General Taylor, delivering

several effective campaign speeches in New England and the West.

At the second session of the Thirtieth Congress, he voted in favor of

laying upon the table a resolution instructing the Committee on the

District of Columbia to report a bill prohibiting the slave-trade in

the District, and subsequently read a substitute which he favored. This

substitute contained the form of a bill enacting that no person not

already within the District, should be held in slavery therein, and

providing for the gradual emancipation of the slaves already within the

District, with compensation to the owners, if a majority of the legal

voters of the District should assent to the act, at an election to be

holden for the purpose. It made an exception of the right of citizens

of the slave-holding States coming to the District on public business,

to “be attended into and out of said District, and while there, by the

necessary servants of themselves and their families.”

In regard to the grant of public lands to the new States, to aid in the

construction of railways and canals, he favored the interests of his

own constituents, under such restrictions as the proper scope of these

grants required.

Having declined to be a candidate for re-election, he retired once

more to private life, resuming the professional practice which had been

temporarily interrupted by his public duties, and taking no active part

in politics through the period of General Taylor’s administration, or

in any of the exciting scenes of 1850.

The introduction of the Kansas-Nebraska bill by Stephen A. Douglas, in

1854, aroused him from his repose, and summoned him once more to battle

for the right. In the canvass of that year, he was one of the most

active leaders of the anti-Nebraska movement, addressing the people

repeatedly from the stump, with all his characteristic earnestness and

energy, and powerfully aided in effecting the remarkable political

changes of that year in Illinois.

The Legislature that year having to choose a United States Senator, and

for the first time in the history of the State, the election of one

opposed to the Democratic party being within the reach of possibility,

Mr. Lincoln, although the first choice of the great body of the

opposition, with characteristic self-sacrificing disposition, appealed

to his old Whig friends to go over in a solid body to Mr. Trumbull,

a man of Democratic antecedents, who could command the full vote of

the anti-Nebraska Democrats; and the latter was consequently elected.

Mr. Lincoln was subsequently offered the nomination for Governor of

Illinois, but declined the honor in favor of Col. William H. Bissell,

who was elected by a decisive majority.

In the formation of the Republican party as such, Mr. Lincoln bore

an active and influential part, his name being presented, but

ineffectually, at the first National Convention of that party, for

Vice-President; laboring earnestly during the canvass of 1856, for the

election of General Fremont, whose electoral ticket he headed.

After Mr. Douglas had taken ground against Mr. Buchanan’s

administration relative to the so-called Lecompton Constitution of

Kansas, and had received the indorsement of the Democratic party of

Illinois--his re-election as Senator depending upon the result of the

State election in 1858--the Republican Convention of that year with

shouts of applause, unanimously resolved that Abraham Lincoln was “the

first and only choice of the Republicans of Illinois for the United

States Senate, as the successor of Stephen A. Douglas.” At the close of

the proceedings, he delivered the following speech, which struck the

key-note of his contest with Senator Douglas, one of the most exciting

and remarkable ever witnessed in this country:

“GENTLEMEN OF THE CONVENTION:--If we could first know where we

are, and whither we are tending, we could then better judge what

to do, and how to do it. We are now far on into the fifth year,

since a policy was initiated, with the avowed object, and confident

promise of putting an end to slavery agitation. Under the operation

of that policy, that agitation had not only not ceased, but has

constantly augmented. In my opinion, it will not cease, until

a crisis shall have been reached, and passed. ‘A house divided

against itself can not stand.’ I believe this Government can not

endure, permanently, half slave and half free. I do not expect the

Union to be dissolved--I do not expect the house to fall--but I do

expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing,

or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest the

further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest

in the belief that it is in course of ultimate extinction, or its

advocates will push it forward, till it shall become alike lawful

in all the States, old as well as new--North as well as South.

“Have we no tendency to the latter condition? Let any one who

doubts, carefully contemplate that now almost complete legal

combination--piece of machinery, so to speak--compounded of the

Nebraska doctrine, and the Dred Scott decision. Let him consider

not only what work the machinery is adapted to do, and how well

adapted, but also let him study the history of its construction,

and trace, if he can, or rather fail, if he can, to trace the

evidences of design, and concert of action, among its chief

master-workers from the beginning.

“But, so far, Congress only had acted; and an indorsement by

the people, real or apparent, was indispensable, to save the

point already gained, and give chance for more. The new year of

1854 found slavery excluded from more than half the States by

State Constitutions, and from most of the national territory by

Congressional prohibition. Four days later commenced the struggle,

which ended in repealing that Congressional prohibition. This

opened all the national territory to slavery, and was the first

point gained.

“This necessity had not been overlooked, but had been

provided for, as well as might be, in the notable argument of

‘_squatter sovereignty_,’ otherwise called ‘_sacred right of

self-government_,’ which latter phrase, though expressive of the

only rightful basis of any government, was so perverted in this

attempted use of it as to amount to just this: that if any one man

choose to enslave another, no third man shall be allowed to object.

That argument was incorporated into the Nebraska Bill itself, in

the language which follows: ‘It being the true intent and meaning

of this act not to legislate slavery into any Territory or State,

nor exclude it therefrom; but to leave the people thereof perfectly

free to form and regulate their domestic institutions in their own

way, subject only to the Constitution of the United States.’

“Then opened the roar of loose declamation in favor of ‘squatter

sovereignty,’ and ‘sacred right of self-government.’

“‘But,’ said opposition members, ‘let us be more specific--let us

_amend_ the bill so as to expressly declare that the people of the

territory _may_ exclude slavery.’ ‘Not we,’ said the friends of the

measure; and down they voted the amendment.

“While the Nebraska Bill was passing through Congress, a law case,

involving the question of a negro’s freedom, by reason of his

owner having voluntarily taken him first into a free State and then

a territory covered by the Congressional prohibition, and held him

as a slave--for a long time in each--was passing through the U. S.

Circuit Court for the District of Missouri; and both the Nebraska

Bill and law suit were brought to a decision in the same month

of May, 1854. The negro’s name was ‘Dred Scott,’ which name now

designates the decision finally made in the case.

“Before the then next Presidential election case, the law came

to, and was argued in the Supreme Court of the United States;

but the decision of it was deferred until _after_ the election.

Still, _before_ the election, Senator Trumbull, on the floor of the

Senate, requests the leading advocate of the Nebraska Bill to state

_his opinion_ whether a people of a territory can constitutionally

exclude slavery from their limits; and the latter answers, ‘That is

a question for the Supreme Court.’

“The election came. Mr. Buchanan was elected, and the

_indorsement_, such as it was, secured. That was the _second_ point

gained. The indorsement, however, fell short of a clear popular

majority by nearly four hundred thousand votes, and so, perhaps,

was not overwhelmingly reliable and satisfactory. The outgoing

President in his last annual message, as impressively as possible

echoed back upon the people the weight and authority of the

indorsement.

“The Supreme Court met again; did not announce their decision, but

ordered a re-argument. The Presidential inauguration came, and

still no decision of the court; but the incoming President, in his

Inaugural Address, fervently exhorted the people to abide by the

forthcoming decision, _whatever it might be_. Then, in a few days

came the decision.

“This was the third point gained.

“The reputed author of the Nebraska Bill finds an early occasion

to make a speech at this capitol indorsing the Dred Scott

decision and vehemently denouncing all opposition to it. The new

President, too, seizes the early occasion of the Silliman letter

to indorse and strongly construe that decision, and to express his

astonishment that any different view had ever been entertained. At

length a squabble springs up between the President and the author

of the Nebraska Bill on the mere question of fact, whether the

Lecompton Constitution was or was not, in any just sense, made by

the people of Kansas; and, in that squabble, the latter declares

that all he wants is a fair vote for the people, and that he cares

not whether slavery be voted down or voted up. I do not understand

his declaration that he cares not whether slavery be voted down or

voted up, to be intended by him other than as an apt definition of

the policy he would impress upon the public mind--the principle for

which he declares he has suffered much, and is ready to suffer to

the end.

“And well may he cling to that principle. If he has any parental

feeling, well may he cling to it. That principle is the only shred

left of his original Nebraska doctrine. Under the Dred Scott

decision, ‘squatter sovereignty’ squatted out of existence, tumbled

down like temporary scaffolding--like the mould at the foundry,

served through one blast, and fell back into loose sand--helped to

carry an election, and then was kicked to the winds. His late joint

struggle with the Republicans, against the Lecompton Constitution,

involves nothing of the original Nebraska doctrine. That struggle

was made on a point--the right of a people to make their own

Constitution--upon which he and the Republicans have never differed.

“The several points of the Dred Scott decision, in connection

with Senator Douglas’s ‘care not’ policy, constitute the piece of

machinery in its present state of advancement. The working points

of that machinery are:

“First, That no negro slave, imported as such from Africa, and no

descendant of such, can ever be a citizen of any State in the

sense of that term as used in the Constitution of the United States.

“This point is made in order to deprive the negro, in every

possible event, of the benefit of this provision of the United

States Constitution, which declares that--‘The citizens of each

State shall be entitled to all the privileges and immunities of

citizens in the several States.’

“Secondly, that ‘subject to the Constitution of the United States,’

neither Congress nor a Territorial Legislature can exclude slavery

from any United States Territory.

“This point is made in order that individual men may fill up the

Territories with slaves, without danger of losing them as property,

and thus to enhance the chances of permanency to the institution

through all the future.

“Thirdly, that whether the holding a negro in actual slavery in

a free State makes him free, as against the holder, the United

States courts will not decide, but will leave it to be decided by

the courts of any slave State the negro may be forced into by the

master.

“This point is made, not to be pressed immediately; but, if

acquiesced in for a while, and apparently indorsed by the people at

an election, then, to sustain the logical conclusion that what Dred

Scott’s master might lawfully do with Dred Scott, in the free State

of Illinois, every other master may lawfully do with any other one,

or one thousand slaves, in Illinois, or in any other free State.

“Auxiliary to all this, and working hand in hand with it, the

Nebraska doctrine, or what is left of it, is to educate and mould

public opinion, at least Northern public opinion, not to care

whether slavery is voted down or voted up.

“This shows exactly where we now are, and partially also, whither

we are tending.

“It will throw additional light on the latter, to go back and

run the mind over the string of historical facts already stated.

Several things will now appear less dark and mysterious than

they did when they were transpiring. The people were to be left

“perfectly free,” “subject only to the Constitution.” What the

Constitution had to do with it, outsiders could not then see.

Plainly enough now, it was an exactly fitted niche for the Dred

Scott decision afterward to come in, and declare that perfect

freedom of the people to be just no freedom at all.

“Why was the amendment expressly declaring the right of the people

to exclude slavery, voted down? Plainly enough now, the adoption of

it would have spoiled the niche for the Dred Scott decision.

“Why was the court decision held up? Why even a Senator’s

individual opinion withheld till after the Presidential election?

Plainly enough now; the speaking out then would have damaged the

“_perfectly free_” argument upon which the election was to be

carried.

“Why the outgoing President’s felicitation on the indorsement? Why

the delay of a re-argument? Why the incoming President’s advance

exhortation in favor of the decision? These things look like the

cautious patting and petting of a spirited horse preparatory to

mounting him, when it is dreaded that he may give the rider a

fall. And why the hasty after-indorsements of the decision, by the

President and others?

“We cannot absolutely know that all these exact adaptations are the

result of pre-concert. But when we see a lot of framed timbers,

different portions of which we know have been gotten out, at

different times and places, and by different workmen--Stephen,

Franklin, Roger, and James, for instance--and when we see these

timbers joined together, and see they exactly make the frame of a

house or a mill, all the tenons and mortices exactly fitting, and

all the lengths and proportions of the different pieces exactly

adapted to their respective places, and not a piece too many or

too few--not omitting even scaffolding--or, if a single piece be

lacking, we can see the place in the frame exactly fitted and

prepared to yet bring such piece in--in such a case, we find it

impossible not to believe that Stephen and Franklin and Roger and

James all understood one another from the beginning, and all worked

upon a common plan or draft drawn up before the first blow was

struck.

“It should not be overlooked that, by the Nebraska bill, the people

of a State as well as Territory, were to be left ‘_perfectly

free_,’ ‘_subject only to the Constitution_.’ Why mention a State?

They were legislating for Territories, and not for or about States.

Certainly the people of a State are and ought to be subject to

the Constitution of the United States; but why is mention of this

lugged into this merely territorial law? Why are the people of

a Territory and the people of a State therein lumped together,

and their relation to the Constitution therein treated as being

precisely the same?

“While the opinion of the court, by Chief Justice Taney, in the

Dred Scott case, and the separate opinions of all the concurring

judges, expressly declare that the Constitution of the United

States neither permits Congress nor a Territorial Legislature, to

exclude slavery from any United States Territory, they all omit to

declare whether or not the same Constitution permits a State, or

the people of a State, to exclude it. _Possibly_, this was a mere

_omission_; but who can be quite sure, if McLean or Curtis had

sought to get into the opinion a declaration of unlimited power in

the people of a State to exclude slavery from their limits, just

as Chase and Mace sought to get such declaration, in behalf of the

people of a Territory, into the Nebraska bill--I ask, who can be

quite sure that it would not have been voted down, in the one case

as it had been in the other.

“The nearest approach to the point of declaring the power of a

State over slavery, is made by Judge Nelson. He approaches it more

than once, using the precise idea, and almost the language, too,

of the Nebraska Act. On one occasion his exact language is, ‘except

in cases where the power is restrained by the Constitution of the

United States, the law of the State is supreme over the subject of

slavery within its jurisdiction.’

“In what cases the power of the State is so restrained by the

United States Constitution, is left an open question, precisely

as the same question, as to the restraint on the power of the

Territories was left open in the Nebraska Act. Put that and that

together, and we have another nice little niche, which we may ere

long, see filled with another Supreme Court decision, declaring

that the Constitution of the United States does not permit a State

to exclude slavery from its limits. And this may especially be

expected if the doctrine of ‘care not whether slavery be voted down

or voted up,’ shall gain upon the public mind sufficiently to give

promise that such a decision can be maintained when made.

“Such a decision is all that slavery now lacks of being alike

lawful in all the States. Welcome or unwelcome, such decision is

probably coming, and will soon be upon us, unless the power of the

present political dynasty shall be met and overthrown. We shall

lie down pleasantly dreaming that the people of Missouri are on

the verge of making their State free; and we shall awake to the

reality, instead, that the Supreme Court has made Illinois a slave

State.

“To meet and overthrow the power of that dynasty, is the work now

before all those who would prevent that consummation. That is what

we have to do. But how can we best do it?

“There are those who denounce us openly to their own friends, and

yet whisper softly, that Senator Douglas is the _aptest_ instrument

there is, with which to effect that object. They do not tell us,

nor has he told us, that he wishes any such object to be effected.

They wish us to infer all, from the facts that he now has a little

quarrel with the present head of the dynasty; and that he has

regularly voted with us, on a single point, upon which he and we

have never differed.

“They remind us that _he_ is a very _great man_, and that the

largest of us are very small ones. Let this be granted. But ‘a

_living dog_ is better than a _dead lion_.’ Judge Douglas, if not

a _dead_ lion for this work, is at least a _caged_ and _toothless_

one. How can he oppose the advances of slavery? He don’t care

anything about it. His avowed mission is impressing the ‘public

heart’ to care nothing about it.

“A leading Douglas Democrat newspaper thinks Douglas’s superior

talent will be needed to resist the revival of the African

slave-trade. Does Douglas believe an effort to revive that trade

is approaching? He has not said so. Does he _really_ think so? But

if it is, how can he resist it? For years he has labored to prove

it a _sacred right_ of white men to take negro slaves into the new

Territories. Can he possibly show that it is less a sacred right

to buy them where they can be bought cheapest? And, unquestionably

they can be bought cheaper in Africa than in Virginia.

“He has done all in his power to reduce the whole question of

slavery to one of a mere right of property; and as such, how can

he oppose the foreign slave-trade--how can he refuse that trade in

that ‘property’ shall be ‘perfectly free’--unless he does it as a

_protection_ to the home production? And as the home _producers_

will probably not ask the protection, he will be wholly without a

ground of opposition.

“Senator Douglas holds, we know, that a man may rightfully be wiser

to-day than he was yesterday--that he may rightfully change when he

finds himself wrong. But can we for that reason run ahead and infer

that he will make any particular change, of which he himself has

given no intimation? Can we safely base our action upon any such

vague inferences?

“Now, as ever, I wish not to misrepresent Judge Douglas’s position,

question his motives, or do aught that can be personally offensive

to him. Whenever, _if ever_, he and we can come together on

_principle_, so that our great cause may have assistance from his

great ability, I hope to have interposed no adventitious obstacle.

“But clearly, he is not now with us--he does not pretend to be--he

does not promise ever to be. Our cause, then, must be intrusted to,

and conducted by its own undoubted friends--those whose hands are

free, whose hearts are in the work--who do care for the result.

“Two years ago the Republicans of the nation mustered over thirteen

hundred thousand strong. We did this under the single impulse of

resistance to a common danger, with every external circumstance

against us. Of strange, discordant, and even hostile elements, we

gathered from the four winds, and formed and fought the battle

through, under the constant hot fire of a disciplined, proud and

pampered enemy. Did we brave all then to falter now?--_now_--when

that same enemy is wavering, dissevered and belligerent?

“The result is not doubtful. We shall not fail--if we stand firm,

we shall not fail. _Wise counsels_ may _accelerate_ or _mistakes

delay_ it, but, sooner or later, the victory is _sure_ to come.”

In this most vigorously prosecuted canvass Illinois was stumped

throughout its length and breadth by both candidates and their

respective advocates, and the struggle was watched with interest by the

country at large. From county to county, from township to township, and

village to village the two champions travelled, frequently in the same

car or carriage, and in the presence of immense crowds of men, women,

and children--for the wives and daughters of the hardy yeomanry were

naturally interested--argued, face to face, the important points of

their political belief and contended nobly for the mastery.

In one of his speeches during this memorable campaign, Mr. Lincoln paid

the following tribute to the Declaration of Independence:--

“These communities, (the thirteen colonies,) by their

representatives in old Independence Hall, said to the world of men,

‘we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are born

equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with inalienable

rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of

happiness.’ This was their majestic interpretation of the economy

of the universe. This was their lofty, and wise, and noble

understanding of the justice of the Creator to His creatures.

Yes, gentlemen, to all His creatures, to the whole great family

of man. In their enlightened belief, nothing stamped with the

Divine image and likeness was sent into the world to be trodden on,

and degraded, and imbruted by its fellows. They grasped not only

the race of men then living, but they reached forward and seized

upon the furthest posterity. They created a beacon to guide their

children and their children’s children, and the countless myriads

who should inhabit the earth in other ages. Wise statesmen as they

were, they knew the tendency of prosperity to breed tyrants, and

so they established these great self-evident truths that when, in

the distant future, some man, some faction, some interest, should

set up the doctrine that none but rich men, or none but white men,

or none but Anglo-Saxon white men, were entitled to life, liberty,

and the pursuit of happiness, their posterity might look up again

to the Declaration of Independence, and take courage to renew the

battle, which their fathers began, so that truth, and justice,

and mercy, and all the humane and Christian virtues might not be

extinguished from the land; so that no man would hereafter dare to

limit and circumscribe the great principles on which the temple of

liberty was being built.

“Now, my countrymen, if you have been taught doctrines conflicting

with the great landmarks of the Declaration of Independence; if

you have listened to suggestions which would take away from its

grandeur, and mutilate the fair symmetry of its proportions; if you

have been inclined to believe that all men are not created equal in

those inalienable rights enumerated by our chart of liberty, let

me entreat you to come back--return to the fountain whose waters

spring close by the blood of the Revolution. Think nothing of me,

take no thought for the political fate of any man whomsoever, but

come back to the truths that are in the Declaration of Independence.

“You may do any thing with me you choose, if you will but heed

these sacred principles. You may not only defeat me for the

Senate, but you may take me and put me to death. While pretending

no indifference to earthly honors, I _do claim_ to be actuated

in this contest by something higher than an anxiety for office.

I charge you to drop every paltry and insignificant thought for

any man’s success. It is nothing; I am nothing; Judge Douglas is

nothing. _But do not destroy that immortal emblem of humanity--the

Declaration of American Independence._”

In the election which closed this contest, the Republican candidate

received 126,084 votes; the Douglas Democrats, 121,940; and the

Lecompton Democrats, 5,091. Mr. Douglas was, however, re-elected

to the Senate by the Legislature, in which, owing to the peculiar

apportionment of the legislative districts his supporters had a

majority of eight in joint ballot.

CHAPTER III.

BEFORE THE NATION.

Speeches in Ohio--Extract from his Cincinnati Speech--Visits

the East--Celebrated Speech at the Cooper Institute, New York--

Interesting Incident.

The issue of this contest with Douglas, seemingly a defeat, was

destined in due time to prove a decisive triumph. Mr. Lincoln’s

reputation as a skillful debater and master of political fence was

secure, and admitted throughout the land. During the year ensuing

he again devoted himself almost exclusively to professional labors,

delivering, however, in the campaign of 1859, at the earnest

solicitation of the Republicans of Ohio, two most convincing speeches

in that State, one at Columbus, and the other at Cincinnati.

In his speech in the latter city, alluding to the certainty of a speedy

Republican triumph in the nation, Mr. Lincoln thus sketched what he

regarded as the inevitable results of such a victory:

“I will tell you, so far as I am authorized to speak for the

opposition, what we mean to do with you. We mean to treat you, as

nearly as we possibly can, as Washington, Jefferson, and Madison

treated you. We mean to leave you alone, and in no way interfere

with your institution; to abide by all and every compromise of

the Constitution; and, in a word, coming back to the original

proposition to treat you, so far as degenerated men (if we have

degenerated) may, imitating the example of those noble fathers,

Washington, Jefferson, and Madison. We mean to remember that you

are as good as we; that there is no difference between us other

than the difference of circumstances. We mean to recognize and

bear in mind always that you have as good hearts in your bosoms as

other people, or as we claim to have, and treat you accordingly.

We mean to marry your girls when we have a chance--the white ones

I mean--and I have the honor to inform you that I once did get a

chance in that way.

“I have told you what we mean to do. I want to know, now, when that

thing takes place, what you mean to do. I often hear it intimated

that you mean to divide the Union whenever a Republican, or any

thing like it, is elected President of the United States. [A voice,

‘That is so.’] ‘That is so,’ one of them says. I wonder if he is a

Kentuckian? [A voice, ‘He is a Douglas man.’] Well, then, I want to

know what you are going to do with your half of it? Are you going

to split the Ohio down through, and push your half off a piece? Or

are you going to keep it right alongside of us outrageous fellows?

Or are you going to build up a wall some way between your country

and ours, by which that movable property of yours can’t come

over here any more, and you lose it? Do you think you can better

yourselves on that subject, by leaving us here under no obligation

whatever to return those specimens of your movable property that

come hither? You have divided the Union because we would not do

right with you, as you think, upon that subject; when we cease to

be under obligations to do any thing for you, how much better off

do you think you will be? Will you make war upon us and kill us

all? Why, gentlemen, I think you are as gallant and as brave men

as live; that you can fight as bravely in a good cause, man for

man, as any other people living; that you have shown yourselves

capable of this upon various occasions; but, man for man, you are

not better than we are, and there are not so many of you as there

are of us. You will never make much of a hand at whipping us. If

we were fewer in numbers than you, I think that you could whip us;

if we were equal it would likely be a drawn battle; but being

inferior in numbers, you will make nothing by attempting to master

us.

“I say that we must not interfere with the institution of Slavery

in the States where it exists, because the Constitution forbids it,

and the general welfare does not require us to do so. We must not

withhold an efficient fugitive slave law because the Constitution

requires us, as I understand it, not to withhold such a law, but we

must prevent the outspreading of the institution, because neither

the constitution nor the general welfare requires us to extend it.

We must prevent the revival of the African slave-trade and the

enacting by Congress of a Territorial slave code. We must prevent

each of these things being done by either Congresses or Courts.

THE PEOPLE OF THESE UNITED STATES ARE THE RIGHTFUL MASTERS OF BOTH

CONGRESSES AND COURTS, not to overthrow the Constitution, but to

overthrow the men who pervert that Constitution.”

In the spring of 1860, Mr. Lincoln yielded to the urgent calls which

came to him from the East for his aid in the exciting canvasses then in

progress in that section, and spoke at various places in Connecticut,

New Hampshire, and Rhode Island, and also in New York city, and was

everywhere warmly welcomed by immense audiences.

Without doubt, one of the greatest speeches of his life was that

delivered by him in the Cooper Institute, in New York, on the 27th of

February, 1860, in the presence of a crowded assembly which received

him with the most enthusiastic demonstrations. We subjoin a full report

of this masterly analysis of men and measures. After being introduced

in highly complimentary terms by the venerable William Cullen Bryant,

who presided on the occasion, he proceeded:

“MR. PRESIDENT AND FELLOW CITIZENS OF NEW YORK:--The facts with

which I shall deal this evening are mainly old and familiar; nor

is there any thing new in the general use I shall make of them. If

there shall be any novelty, it will be in the mode of presenting

the facts, and the inferences and observations following that

presentation.

“In his speech last autumn, at Columbus, Ohio, as reported in _The

New York Times_, Senator Douglas said:

“‘Our fathers, when they framed the Government under which we live,

understood this question just as well, and even better than we do

now.’

“I fully indorse this and I adopt it as a text for this discourse.

I so adopt it because it furnishes a precise and agreed starting

point for the discussion between Republicans and that wing of

Democracy headed by Senator Douglas. It simply leaves the inquiry:

‘What was the understanding those fathers had of the questions

mentioned?’

“What is the frame of Government under which we live?

“The answer must be: ‘The Constitution of the United States.’ That

Constitution consists of the original, framed in 1787 (and under

which the present Government first went into operation), and twelve

subsequently framed amendments, the first ten of which were framed

in 1789.

“Who were our fathers that framed the Constitution? I suppose

the ‘thirty-nine’ who signed the original instrument may be

fairly called our fathers who framed that part of the present

Government. It is almost exactly true to say they framed it, and

it is altogether true to say they fairly represented the opinion

and sentiment of the whole nation at that time. Their names being

familiar to nearly all, and accessible to quite all, need not now

be repeated.

“I take these ‘thirty-nine,’ for the present, as being ‘our fathers

who framed the Government under which we live.’

“What is the question which, according to the text, those fathers

understood just as well, and even better than we do now?

“It is this: Does the proper division of local from federal

authority, or any thing in the Constitution, forbid our Federal

Government control as to slavery in our Federal Territories?

“Upon this, Douglas holds the affirmative, and Republicans the

negative. This affirmative and denial form an issue; and this

issue--this question--is precisely what the text declares our

fathers understood better than we.

“Let us now inquire whether the ‘thirty-nine,’ or any of them, ever

acted upon this question; and if they did, how they acted upon

it--how they expressed that better understanding.

“In 1784--three years before the Constitution--the United States

then owning the Northwestern Territory, and no other--the Congress

of the Confederation had before them the question of prohibiting

slavery in that Territory; and four of the ‘thirty-nine’ who

afterward framed the Constitution were in that Congress, and voted

on that question. Of these, Roger Sherman, Thomas Mifflin, and Hugh

Williamson voted for the prohibition--thus showing that, in their

understanding, no line dividing local from federal authority, nor

any thing else, properly forbade the Federal Government to control

as to slavery in federal territory. The other of the four--James

McHenry--voted against the prohibition, showing that, for some

cause, he thought it improper to vote for it.

“In 1787, still before the Constitution, but while the Convention

was in session framing it, and while the Northwestern Territory

still was the only territory owned by the United States--the

same question of prohibiting slavery in the territory again came

before the Congress of the Confederation; and three more of the

‘thirty-nine’ who afterward signed the Constitution, were in that

Congress, and voted on the question. They were William Blount,

William Few, and Abraham Baldwin; and they all voted for the

prohibition--thus showing that, in their understanding, no line

dividing local from federal authority, nor any thing else, properly

forbids the Federal Government to control as to slavery in federal

territory. This time the prohibition became a law, being part of

what is now well known as the Ordinance of ’87.

“The question of federal control of slavery in the territories,

seems not to have been directly before the Convention which framed

the original Constitution; and hence it is not recorded that the

‘thirty-nine’ or any of them, while engaged on that instrument,

expressed any opinion on that precise question.

“In 1789, by the First congress which sat under the Constitution,

an act was passed to enforce the Ordinance of ’87 including the

prohibition of slavery in the Northwestern Territory. The bill

for this act was reported by one of the ‘thirty-nine,’ Thomas

Fitzsimmons, then a member of the House of Representatives from

Pennsylvania. It went through all its stages without a word of

opposition, and finally passed both branches without yeas and nays,

which is equivalent to an unanimous passage. In this Congress there

were sixteen of the ‘thirty-nine’ fathers who framed the original

Constitution. They were John Langdon, Nicholas Gilman, Wm. S.

Johnson, Roger Sherman, Robert Morris, Thos. Fitzsimmons, William

Few, Abraham Baldwin, Rufus King, William Patterson, George Clymer,

Richard Bassett, George Read, Pierce Butler, Daniel Carrol, James

Madison.

“This shows that, in their understanding, no line dividing local

from federal authority, nor any thing in the Constitution, properly

forbade Congress to prohibit slavery in the federal territory;

else both their fidelity to correct principle, and their oath to

support the Constitution, would have constrained them to oppose the

prohibition.

“Again, George Washington, another of the ‘thirty-nine,’ was then

President of the United States, and, as such, approved and signed

the bill, thus completing its validity as a law, and thus showing

that, in his understanding, no line dividing local from federal

authority, nor any thing in the Constitution, forbade the Federal

Government to control as to slavery in Federal territory.

“No great while after the adoption of the original Constitution,

North Carolina ceded to the Federal Government the country now

constituting the State of Tennessee; and a few years later Georgia

ceded that which now constitutes the States of Mississippi and

Alabama. In both deeds of cession it was made a condition by the

ceding States that the Federal Government should not prohibit

slavery in the ceded country. Besides this, slavery was then

actually in the ceded country. Under these circumstances, Congress,

on taking charge of these countries did not absolutely prohibit

slavery within them. But they did interfere with it--take control

of it--even there, to a certain extent. In 1798, Congress organized

the Territory of Mississippi. In the act of organization they

prohibited the bringing of slaves into the Territory, from any

place without the United States, by fine and giving freedom to

slaves so brought. This act passed both branches of Congress

without yeas and nays. In that Congress were three of the

‘thirty-nine’ who framed the original Constitution. They were John

Langdon, George Read, and Abraham Baldwin. They all, probably,

voted for it. Certainly they would have placed their opposition to

it upon record, if, in their understanding, any line dividing local

from Federal authority, or any thing in the Constitution, properly

forbade the Federal Government to control as to slavery in Federal

territory.

“In 1803, the Federal Government purchased the Louisiana country.

Our former territorial acquisitions came from certain of our own

States; but this Louisiana country was acquired from a foreign

nation. In 1804, Congress gave a territorial organization to that

part of it which now constitutes the State of Louisiana. New

Orleans, lying within that part, was an old and comparatively

large city. There were other considerable towns and settlements,

and slavery was extensively and thoroughly intermingled with

the people. Congress did not, in the Territorial Act, prohibit

slavery; but they did interfere with it--take control of it--in

a more marked and extensive way than they did in the case of

Mississippi. The substance of the provision therein made, in

relation to slaves, was:

“_First._ That no slave should be imported into the territory from

foreign parts.

“_Second._ That no slave should be carried into it who had been

imported into the United States since the first day of May, 1798.

“_Third._ That no slave should be carried into it, except by the

owner, and for his own use as a settler; the penalty in all the

cases being a fine upon the violator of the law, and freedom to the

slave.

“This act also was passed without yeas and nays. In the Congress

which passed it, there were two of the ‘thirty-nine.’ They were

Abraham Baldwin and Jonathan Dayton. As stated in the case of

Mississippi, it is probable they both voted for it. They would not

have allowed it to pass without recording their opposition to it,

if, in their understanding, it violated either the line proper

dividing local from Federal authority or any provision of the

Constitution.

“In 1819-20, came and passed the Missouri question. Many votes

were taken, by yeas and nays, in both branches of Congress,

upon the various phases of the general question. Two of the

‘thirty-nine’--Rufus King and Charles Pinckney--were members of

that Congress. Mr. King steadily voted for slavery prohibition

and against all compromises, while Mr. Pinckney as steadily voted

against slavery prohibition and against all compromises. By this

Mr. King showed that, in his understanding, no line dividing local

from Federal authority, nor any thing in the Constitution, was

violated by Congress prohibiting slavery in Federal territory;

while Mr. Pinckney, by his votes, showed that in his understanding

there was some sufficient reason for opposing such prohibition in

that case.

“The cases I have mentioned are the only acts of the ‘thirty-nine,’

or of any of them, upon the direct issue, which I have been able to

discover.

“To enumerate the persons who thus acted, as being four in 1784,

three in 1787, seventeen in 1789, three in 1798, two in 1804, and

two in 1819-20--there would be thirty-one of them. But this would

be counting John Langdon, Roger Sherman, William Few, Rufus King,

and George Read, each twice, and Abraham Baldwin four times. The

true number of those of the ‘thirty-nine’ whom I have shown to have

acted upon the question, which, by the text they understood better

than we, is twenty-three, leaving sixteen not shown to have acted

upon it in any way.

“Here, then, we have twenty-three out of our ‘thirty-nine’ fathers

who framed the government under which we live, who have, upon

their official responsibility and their corporal oaths, acted upon

the very question which the text affirms they ‘understood just as

well, and even better than we do now;’ and twenty-one of them--a

clear majority of the ‘thirty-nine’--so acting upon it as to make

them guilty of gross political impropriety, and wilful perjury,

if, in their understanding, any proper division between local and

Federal authority, or any thing in the Constitution they had made

themselves, and sworn to support, forbade the Federal Government

to control as to slavery in the Federal territories. Thus the

twenty-one acted; and, as actions speak louder than words, so

actions under such responsibility speak still louder.

“Two of the twenty-three voted against Congressional prohibition of

slavery in the Federal Territories, in the instances in which they

acted upon the question. But for what reasons they so voted is not

known. They may have done so because they thought a proper division

of local from Federal authority, or some provision or principle of

the Constitution, stood in the way; or they may, without any such

question, have voted against the prohibition, on what appeared to

them to be sufficient grounds of expediency. No one who has sworn

to support the Constitution, can conscientiously vote for what he

understands to be an unconstitutional measure, however expedient

he may think it; but one may and ought to vote against a measure

which he deems constitutional, if, at the same time, he deems it

inexpedient. It, therefore, would be unsafe to set down even the

two who voted against the prohibition, as having done so because,