*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 73575 ***

The HOUNDS of TINDALOS

By Frank Belknap Long, Jr.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Weird Tales March 1929.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

"I'm glad you came," said Chalmers. He was sitting by the window and

his face was very pale. Two tall candles guttered at his elbow and cast

a sickly amber light over his long nose and slightly receding chin.

Chalmers would have nothing modern about his apartment. He had the soul

of a mediæval ascetic, and he preferred illuminated manuscripts to

automobiles and leering stone gargoyles to radios and adding-machines.

As I crossed the room to the settee he had cleared for me I glanced at

his desk and was surprized to discover that he had been studying the

mathematical formulæ of a celebrated contemporary physicist, and that

he had covered many sheets of thin yellow paper with curious geometric

designs.

"Einstein and John Dee are strange bedfellows," I said as my gaze

wandered from his mathematical charts to the sixty or seventy quaint

books that comprised his strange little library. Plotinus and Emanuel

Moscopulus, St. Thomas Aquinas and Frenicle de Bessy stood elbow to

elbow in the somber ebony bookcase, and chairs, table and desk were

littered with pamphlets about mediæval sorcery and witchcraft and black

magic, and all of the valiant glamorous things that the modern world

has repudiated.

Chalmers smiled engagingly, and passed me a Russian cigarette on a

curiously carved tray. "We are just discovering now," he said, "that

the old alchemists and sorcerers were two-thirds _right_, and that your

modern biologist and materialist is nine-tenths _wrong_."

"You have always scoffed at modern science," I said, a little

impatiently.

"Only at scientific dogmatism," he replied. "I have always been a

rebel, a champion of originality and lost causes; that is why I have

chosen to repudiate the conclusions of contemporary biologists."

"And Einstein?" I asked.

"A priest of transcendental mathematics!" he murmured reverently. "A

profound mystic and explorer of the great _suspected_."

"Then you do not entirely despise science."

"Of course not," he affirmed. "I merely distrust the scientific

positivism of the past fifty years, the positivism of Haeckel and

Darwin and of Mr. Bertrand Russell. I believe that biology has failed

pitifully to explain the mystery of man's origin and destiny."

"Give them time," I retorted.

Chalmers' eyes glowed. "My friend," he murmured, "your pun is sublime.

Give them _time_. That is precisely what I would do. But your modern

biologist scoffs at time. He has the key but he refuses to use it. What

do we know of time, really? Einstein believes that it is relative, that

it can be interpreted in terms of space, of _curved_ space. But must we

stop there? When mathematics fails us can we not advance by--insight?"

"You are treading on dangerous ground," I replied. "That is a pit-fall

that your true investigator avoids. That is why modern science has

advanced so slowly. It accepts nothing that it can not demonstrate. But

you----"

"I would take hashish, opium, all manner of drugs. I would emulate the

sages of the East. And then perhaps I would apprehend----"

"What?"

"The fourth dimension."

"Theosophical rubbish!"

"Perhaps. But I believe that drugs expand human consciousness. William

James agreed with me. And I have discovered a new one."

"A new drug?"

"It was used centuries ago by Chinese alchemists, but it is virtually

unknown in the West. Its occult properties are amazing. With its aid

and the aid of my mathematical knowledge I believe that I can _go back

through time_."

"I do not understand."

"Time is merely our imperfect perception of a new dimension of space.

Time and motion are both illusions. Everything that has existed from

the beginning of the world _exists now_. Events that occurred centuries

ago on this planet continue to exist in another dimension of space.

Events that will occur centuries from now _exist already_. We can

not perceive their existence because we can not enter the dimension

of space that contains them. Human beings as we know them are merely

fractions, infinitesimally small fractions of one enormous whole. Every

human being is linked with _all_ the life that has preceded him on this

planet. All of his ancestors are parts of him. Only time separates him

from his forebears, and time is an illusion and does not exist."

"I think I understand," I murmured.

"It will be sufficient for my purpose if you can form a vague idea

of what I wish to achieve. I wish to strip from my eyes the veils of

illusion that time has thrown over them, and see the _beginning and the

end_."

"And you think this new drug will help you?"

"I am sure that it will. And I want you to help me. I intend to take

the drug immediately. I can not wait. I must _see_." His eyes glittered

strangely. "I am going back, back through time."

He rose and strode to the mantel. When he faced me again he was holding

a small square box in the palm of his hand. "I have here five pellets

of the drug Liao. It was used by the Chinese philosopher Lao Tze, and

while under its influence he visioned Tao. Tao is the most mysterious

force in the world; it surrounds and pervades all things; it contains

the visible universe and everything that we call reality. He who

apprehends the mysteries of Tao sees clearly all that was and will be."

"Rubbish!" I retorted.

"Tao resembles a great animal, recumbent, motionless, containing in its

enormous body all the worlds of our universe, the past, the present and

the future. We see portions of this great monster through a slit, which

we call time. With the aid of this drug I shall enlarge the slit. I

shall behold the great figure of life, the great recumbent beast in its

entirety."

"And what do you wish me to do?"

"Watch, my friend. Watch and take notes. And if I go back too far you

must recall me to reality. You can recall me by shaking me violently.

If I appear to be suffering acute physical pain you must recall me at

once."

"Chalmers," I said, "I wish you wouldn't make this experiment. You

are taking dreadful risks. I don't believe that there is any fourth

dimension and I emphatically do not believe in Tao. And I don't approve

of your experimenting with unknown drugs."

"I know the properties of this drug," he replied. "I know precisely

how it affects the human animal and I know its dangers. The risk does

not reside in the drug itself. My only fear is that I may become

lost in time. You see, I shall assist the drug. Before I swallow

this pellet I shall give my undivided attention to the geometric and

algebraic symbols that I have traced on this paper." He raised the

mathematical chart that rested on his knee. "I shall prepare my mind

for an excursion into time. I shall _approach_ the fourth dimension

with my conscious mind before I take the drug which will enable me to

exercise occult powers of perception. Before I enter the dream world of

the Eastern mystics I shall acquire all of the mathematical help that

modern science can offer. This mathematical knowledge, this conscious

approach to an actual apprehension of the fourth dimension of time

will supplement the work of the drug. The drug will open up stupendous

new vistas--the mathematical preparation will enable me to grasp them

intellectually. I have often grasped the fourth dimension in dreams,

emotionally, intuitively, but I have never been able to recall, in

waking life, the occult splendors that were momentarily revealed to me.

"But with your aid, I believe that I can recall them. You will take

down everything that I say while I am under the influence of the drug.

No matter how strange or incoherent my speech may become you will omit

nothing. When I awake I may be able to supply the key to whatever is

mysterious or incredible. I am not sure that I shall succeed, but if I

_do_ succeed"--his eyes were strangely luminous--"_time will exist for

me no longer!_"

He sat down abruptly. "I shall make the experiment at once. Please

stand over there by the window and watch. Have you a fountain pen?"

I nodded gloomily and removed a pale green Waterman from my upper vest

pocket.

"And a pad, Frank?"

I groaned and produced a memorandum book. "I emphatically disapprove of

this experiment," I muttered. "You're taking a frightful risk."

"Don't be an asinine old woman!" he admonished. "Nothing that you can

say will induce me to stop now. I entreat you to remain silent while I

study these charts."

He raised the charts and studied them intently. I watched the clock on

the mantel as it ticked out the seconds, and a curious dread clutched

at my heart so that I choked.

Suddenly the clock stopped ticking, and exactly at that moment Chalmers

swallowed the drug.

* * * * *

I rose quickly and moved toward him, but his eyes implored me not to

interfere. "The clock has stopped," he murmured. "The forces that

control it approve of my experiment. _Time_ stopped, and I swallowed

the drug. I pray God that I shall not lose my way."

He closed his eyes and leaned back on the sofa. All of the blood had

left his face and he was breathing heavily. It was clear that the drug

was acting with extraordinary rapidity.

"It is beginning to get dark," he murmured. "Write that. It is

beginning to get dark and the familiar objects in the room are fading

out. I can discern them vaguely through my eyelids but they are fading

swiftly."

I shook my pen to make the ink come and wrote rapidly in shorthand as

he continued to dictate.

"I am leaving the room. The walls are vanishing and I can no longer see

any of the familiar objects. Your face, though, is still visible to me.

I hope that you are writing. I think that I am about to make a great

leap--a leap through space. Or perhaps it is through time that I shall

make the leap. I can not tell. Everything is dark, indistinct."

He sat for a while silent, with his head sunk upon his breast. Then

suddenly he stiffened and his eyelids fluttered open. "God in heaven!"

he cried. "I _see_!"

He was straining forward in his chair, staring at the opposite wall.

But I knew that he was looking beyond the wall and that the objects in

the room no longer existed for him. "Chalmers," I cried, "Chalmers,

shall I wake you?"

"Do not!" he shrieked. "I see _everything_. All of the billions of

lives that preceded me on this planet are before me at this moment. I

see men of all ages, all races, all colors. They are fighting, killing,

building, dancing, singing. They are sitting about rude fires on lonely

gray deserts, and flying through the air in monoplanes. They are riding

the seas in bark canoes and enormous steamships; they are painting

bison and mammoths on the walls of dismal caves and covering huge

canvases with queer futuristic designs. I watch the migrations from

Atlantis. I watch the migrations from Lemuria. I see the elder races--a

strange horde of black dwarfs overwhelming Asia and the Neandertalers

with lowered heads and bent knees ranging obscenely across Europe.

I watch the Achæans streaming into the Greek islands, and the crude

beginnings of Hellenic culture. I am in Athens and Pericles is young. I

am standing on the soil of Italy. I assist in the rape of the Sabines;

I march with the Imperial Legions. I tremble with awe and wonder as

the enormous standards go by and the ground shakes with the tread of

the victorious _hastati_. A thousand naked slaves grovel before me as

I pass in a litter of gold and ivory drawn by night-black oxen from

Thebes, and the flower-girls scream '_Ave Cæsar_' as I nod and smile.

I am myself a slave on a Moorish galley. I watch the erection of a

great cathedral. Stone by stone it rises, and through months and years

I stand and watch each stone as it falls into place. I am burned on a

cross head downward in the thyme-scented gardens of Nero, and I watch

with amusement and scorn the torturers at work in the chambers of the

Inquisition.

"I walk in the holiest sanctuaries; I enter the temples of Venus. I

kneel in adoration before the Magna Mater, and I throw coins on the

bare knees of the sacred courtezans who sit with veiled faces in the

groves of Babylon. I creep into an Elizabethan theater and with the

stinking rabble about me I applaud _The Merchant of Venice_. I walk

with Dante through the narrow streets of Florence. I meet the young

Beatrice and the hem of her garment brushes my sandals as I stare

enraptured. I am a priest of Isis, and my magic astounds the nations.

Simon Magus kneels before me, imploring my assistance, and Pharaoh

trembles when I approach. In India I talk with the Masters and run

screaming from their presence, for their revelations are as salt on

wounds that bleed.

"I perceive everything _simultaneously_. I perceive everything from all

sides; I am a part of all the teeming billions about me. I exist in all

men and all men exist in me. I perceive the whole of human history in a

single instant, the past and the present.

"By simply _straining_ I can see farther and farther back. Now I

am going back through strange curves and angles. Angles and curves

multiply about me. I perceive great segments of time through _curves_.

There is _curved time_, and _angular time_. The beings that exist in

angular time can not enter curved time. It is very strange.

"I am going back and back. Man has disappeared from the earth. Gigantic

reptiles crouch beneath enormous palms and swim through the loathly

black waters of dismal lakes. Now the reptiles have disappeared. No

animals remain upon the land, but beneath the waters, plainly visible

to me, dark forms move slowly over the rotting vegetation.

"The forms are becoming simpler and simpler. Now they are single cells.

All about me there are angles--strange angles that have no counterparts

on the earth. I am desperately afraid.

"There is an abyss of being which man has never fathomed."

I stared. Chalmers had risen to his feet and he was gesticulating

helplessly with his arms. "I am passing through _unearthly_ angles; I

am approaching--oh, the burning horror of it!"

"Chalmers!" I cried. "Do you wish me to interfere?"

He brought his right hand quickly before his face, as though to shut

out a vision unspeakable. "Not yet!" he cried; "I will go on. I will

see--what--lies--beyond----"

A cold sweat streamed from his forehead and his shoulders jerked

spasmodically. "Beyond life there are"--his face grew ashen with

terror--"_things_ that I can not distinguish. They move slowly through

angles. They have no bodies, and they move slowly through outrageous

angles."

It was then that I became aware of the odor in the room. It was a

pungent, indescribable odor, so nauseous that I could scarcely endure

it. I stepped quickly to the window and threw it open. When I returned

to Chalmers and looked into his eyes I nearly fainted.

"I think they have scented me!" he shrieked. "They are slowly turning

toward me."

He was trembling horribly. For a moment he clawed at the air with his

hands. Then his legs gave way beneath him and he fell forward on his

face, slobbering and moaning.

I watched him in silence as he dragged himself across the floor. He

was no longer a man. His teeth were bared and saliva dripped from the

corners of his mouth.

"Chalmers," I cried. "Chalmers, stop it! Stop it, do you hear?"

As if in reply to my appeal he commenced to utter hoarse convulsive

sounds which resembled nothing so much as the barking of a dog, and

began a sort of hideous writhing in a circle about the room. I bent and

seized him by the shoulders. Violently, desperately, I shook him. He

turned his head and snapped at my wrist. I was sick with horror, but

I dared not release him for fear that he would destroy himself in a

paroxysm of rage.

"Chalmers," I muttered, "you must stop that. There is nothing in this

room that can harm you. Do you understand?"

I continued to shake and admonish him, and gradually the madness died

out of his face. Shivering convulsively, he crumpled into a grotesque

heap on the Chinese rug.

* * * * *

I carried him to the sofa and deposited him upon it. His features were

twisted in pain, and I knew that he was still struggling dumbly to

escape from abominable memories.

"Whisky," he muttered. "You'll find a flask in the cabinet by the

window--upper left-hand drawer."

When I handed him the flask his fingers tightened about it until the

knuckles showed blue. "They nearly got me," he gasped. He drained the

stimulant in immoderate gulps, and gradually the color crept back into

his face.

"That drug was the very devil!" I murmured.

"It wasn't the drug," he moaned.

His eyes no longer glared insanely, but he still wore the look of a

lost soul.

"They scented me in time," he moaned. "I went too far."

"What were _they_ like?" I said, to humor him.

He leaned forward and gripped my arm. He was shivering horribly. "No

word in our language can describe them!" He spoke in a hoarse whisper.

"They are symbolized vaguely in the myth of the Fall, and in an obscene

form which is occasionally found engraven on ancient tablets. The

Greeks had a name for them, which veiled their essential foulness. The

tree, the snake and the apple--these are the vague symbols of a most

awful mystery."

His voice had risen to a scream. "Frank, Frank, a terrible and

unspeakable _deed_ was done in the beginning. Before time, the _deed_,

and from the deed----"

He had risen and was hysterically pacing the room. "The seeds of the

deed move through angles in dim recesses of time. They are hungry and

athirst!"

"Chalmers," I pleaded to quiet him. "We are living in the third decade

of the Twentieth Century."

"They are lean and athirst!" he shrieked. "_The Hounds of Tindalos!_"

"Chalmers, shall I phone for a physician?"

"A physician can not help me now. They are horrors of the soul, and

yet"--he hid his face in his hands and groaned--"they are real, Frank.

I saw them for a ghastly moment. For a moment I stood on the _other

side_. I stood on the pale gray shores beyond time and space. In an

awful light that was not light, in a silence that shrieked, I saw

_them_.

"All the evil in the universe was concentrated in their lean, hungry

bodies. Or had they bodies? I saw them only for a moment; I can not

be certain. _But I heard them breathe._ Indescribably for a moment

I felt their breath upon my face. They turned toward me and I fled

screaming. In a single moment I fled screaming through time. I fled

down quintillions of years.

"But they scented me. Men awake in them cosmic hungers. We have

escaped, momentarily, from the foulness that rings them round. They

thirst for that in us which is clean, which emerged from the deed

without stain. There is a part of us which did not partake in the

deed, and that they hate. But do not imagine that they are literally,

prosaically evil. They are beyond good and evil as we know it. They are

that which in the beginning fell away from cleanliness. Through the

deed they became bodies of death, receptacles of all foulness. But they

are not evil in our sense because in the spheres through which they

move there is no thought, no morals, no right or wrong as we understand

it. There is merely the pure and the foul. The foul expresses itself

through angles; the pure through curves. Man, the pure part of him, is

descended from a curve. Do not laugh. I mean that literally."

I rose and searched for my hat. "I'm dreadfully sorry for you,

Chalmers," I said, as I walked toward the door. "But I don't intend to

stay and listen to such gibberish. I'll send my physician to see you.

He's an elderly, kindly chap and he won't be offended if you tell him

to go to the devil. But I hope you'll respect his advice. A week's rest

in a good sanitarium should benefit you immeasurably."

I heard him laughing as I descended the stairs, but his laughter was so

utterly mirthless that it moved me to tears.

2

When Chalmers phoned the following morning my first impulse was to hang

up the receiver immediately. His request was so unusual and his voice

was so wildly hysterical that I feared any further association with him

would result in the impairment of my own sanity. But I could not doubt

the genuineness of his misery, and when he broke down completely and I

heard him sobbing over the wire I decided to comply with his request.

"Very well," I said. "I will come over immediately and bring the

plaster."

En route to Chalmers' home I stopped at a hardware store and purchased

twenty pounds of plaster of Paris. When I entered my friend's room he

was crouching by the window watching the opposite wall out of eyes that

were feverish with fright. When he saw me he rose and seized the parcel

containing the plaster with an avidity that amazed and horrified me.

He had extruded all of the furniture and the room presented a desolate

appearance.

"It is just conceivable that we can thwart them!" he exclaimed. "But we

must work rapidly. Frank, there is a stepladder in the hall. Bring it

here immediately. And then fetch a pail of water."

"What for?" I murmured.

He turned sharply and there was a flush on his face. "To mix the

plaster, you fool!" he cried. "To mix the plaster that will save our

bodies and souls from a contamination unmentionable. To mix the

plaster that will save the world from--Frank, _they must be kept out_!"

"Who?" I murmured.

"The Hounds of Tindalos!" he muttered. "They can only reach us through

angles. We must eliminate all angles from this room. I shall plaster

up all of the corners, all of the crevices. We must make this room

resemble the interior of a sphere."

I knew that it would have been useless to argue with him. I fetched the

stepladder, Chalmers mixed the plaster, and for three hours we labored.

We filled in the four corners of the wall and the intersections of

the floor and wall and the wall and ceiling, and we rounded the sharp

angles of the window-seat.

"I shall remain in this room until they return in time," he affirmed

when our task was completed. "When they discover that the scent leads

through curves they will return. They will return ravenous and snarling

and unsatisfied to the foulness that was in the beginning, before time,

beyond space."

He nodded graciously and lit a cigarette. "It was good of you to help,"

he said.

"Will you not see a physician, Chalmers?" I pleaded.

"Perhaps--tomorrow," he murmured. "But now I must watch and wait."

"Wait for what?" I urged.

Chalmers smiled wanly. "I know that you think me insane," he said. "You

have a shrewd but prosaic mind, and you can not conceive of an entity

that does not depend for its existence on force and matter. But did

it ever occur to you, my friend, that force and matter are merely the

barriers to perception imposed by time and space? When one knows, as I

do, that time and space are identical and that they are both deceptive

because they are merely imperfect manifestations of a higher reality,

one no longer seeks in the visible world for an explanation of the

mystery and terror of being."

I rose and walked toward the door.

"Forgive me," he cried. "I did not mean to offend you. You have a

superlative intellect, but I--I have a _superhuman_ one. It is only

natural that I should be aware of your limitations."

"Phone if you need me," I said, and descended the stairs two steps at

a time. "I'll send my physician over at once," I muttered, to myself.

"He's a hopeless maniac, and heaven knows what will happen if someone

doesn't take charge of him immediately."

3

_The following is a condensation of two announcements which appeared in

the_ Partridgeville Gazette _for July 3, 1928_:

Earthquake Shakes Financial District

At 2 o'clock this morning an earth tremor of unusual severity

broke several plate-glass windows in Central Square and completely

disorganized the electric and street railway systems. The tremor

was felt in the outlying districts and the steeple of the First

Baptist Church on Angell Hill (designed by Christopher Wren in

1717) was entirely demolished. Firemen are now attempting to put

out a blaze which threatens to destroy the Partridgeville Glue

Works. An investigation is promised by the mayor and an immediate

attempt will be made to fix responsibility for this disastrous

occurrence.

* * * * *

OCCULT WRITER MURDERED BY UNKNOWN GUEST

Horrible Crime in Central Square

Mystery Surrounds Death of Halpin Chalmers

At 9 a.m. today the body of Halpin Chalmers, author and

journalist, was found in an empty room above the jewelry store

of Smithwick and Isaacs, 24 Central Square. The coroner's

investigation revealed that the room had been rented _furnished_

to Mr. Chalmers on May 1, and that he had himself disposed of the

furniture a fortnight ago. Chalmers was the author of several

recondite books on occult themes, and a member of the Bibliographic

Guild. He formerly resided in Brooklyn, New York.

At 7 a.m. Mr. L. E. Hancock, who occupies the apartment opposite

Chalmers' room in the Smithwick and Isaacs establishment, smelt

a peculiar odor when he opened his door to take in his cat and

the morning edition of the _Partridgeville Gazette_. The odor he

describes as extremely acrid and nauseous, and he affirms that it

was so strong in the vicinity of Chalmers' room that he was obliged

to hold his nose when he approached that section of the hall.

He was about to return to his own apartment when it occurred to him

that Chalmers might have accidentally forgotten to turn off the gas

in his kitchenette. Becoming considerably alarmed at the thought,

he decided to investigate, and when repeated tappings on Chalmers'

door brought no response he notified the superintendent. The latter

opened the door by means of a pass key, and the two men quickly

made their way into Chalmers' room. The room was utterly destitute

of furniture, and Hancock asserts that when he first glanced at the

floor his heart went cold within him, and that the superintendent,

without saying a word, walked to the open window and stared at the

building opposite for fully five minutes.

Chalmers lay stretched upon his back in the center of the room.

He was starkly nude, and his chest and arms were covered with a

peculiar bluish pus or ichor. His head lay grotesquely upon his

chest. It had been completely severed from his body, and the

features were twisted and torn and horribly mangled. Nowhere was

there a trace of blood.

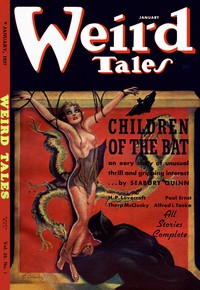

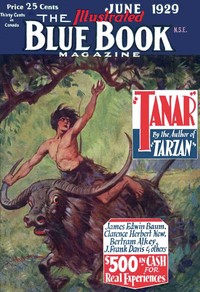

[Illustration: "He was starkly nude, and twisted and torn."]

The room presented a most astonishing appearance. The intersections

of the walls, ceiling and floor had been thickly smeared with

plaster of Paris, but at intervals fragments had cracked and

fallen off, and someone had grouped these upon the floor about the

murdered man so as to form a perfect triangle.

Beside the body were several sheets of charred yellow paper. These

bore fantastic geometric designs and symbols and several hastily

scrawled sentences. The sentences were almost illegible and so

absurd in context that they furnished no possible clue to the

perpetrator of the crime. "I am waiting and watching," Chalmers

wrote. "I sit by the window and watch walls and ceiling. I do not

believe they can reach me, but I must beware of the Doels. Perhaps

_they_ can help them break through. The satyrs will help, and they

can advance through the scarlet circles. The Greeks knew a way of

preventing that. It is a great pity that we have forgotten so much."

On another sheet of paper, the most badly charred of the seven

or eight fragments found by Detective Sergeant Douglas (of the

Partridgeville Reserve), was scrawled the following:

"Good God, the plaster is falling! A terrific shock has loosened

the plaster and it is falling. An earthquake perhaps! I never could

have anticipated this. It is growing dark in the room. I must phone

Frank. But can he get here in time? I will try. I will recite the

Einstein formula. I will--God, they are breaking through! They are

breaking through! Smoke is pouring from the corners of the wall.

Their _tongues_--ahhhhh----"

In the opinion of Detective Sergeant Douglas, Chalmers was poisoned

by some obscure chemical. He has sent specimens of the strange

blue slime found on Chalmers' body to the Partridgeville Chemical

Laboratories; and he expects the report will shed new light on

one of the most mysterious crimes of recent years. That Chalmers

entertained a guest on the evening preceding the earthquake

is certain, for his neighbor distinctly heard a low murmur of

conversation in the former's room as he passed it on his way to the

stairs. Suspicion points strongly to this unknown visitor and the

police are diligently endeavoring to discover his identity.

4

_Report of James Morton, chemist and bacteriologist_:

My dear Mr. Douglas:

The fluid sent to me for analysis is the most peculiar that I

have ever examined. It resembles living protoplasm, but it lacks

the peculiar substances known as enzymes. Enzymes catalyze the

chemical reactions occurring in living cells, and when the cell

dies they cause it to disintegrate by hydrolyzation. Without

enzymes protoplasm should possess enduring vitality, i.e.,

immortality. Enzymes are the negative components, so to speak, of

unicellular organism, which is the basis of all life. That living

matter can exist without enzymes biologists emphatically deny.

And yet the substance that you have sent me is alive and it lacks

these "indispensable" bodies. Good God, sir, do you realize what

astounding new vistas this opens up?

5

_Excerpt from_ The Secret Watchers _by the late Halpin Chalmers_:

What if, parallel to the life we know, there is another life that

does not die, which lacks the elements that destroy _our_ life?

Perhaps in another dimension there is a _different_ force from

that which generates our life. Perhaps this force emits energy,

or something similar to energy, which passes from the unknown

dimension where _it_ is and creates a new form of cell life in

our dimension. No one knows that such new cell life does exist in

our dimension. Ah, but I have seen _its_ manifestations. I have

_talked_ with them. In my room at night I have talked with the

Doels. And in dreams I have seen their maker. I have stood on the

dim shore beyond time and matter and seen _it_. _It_ moves through

strange curves and outrageous angles. Some day I shall travel in

time and meet _it_ face to face.

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 73575 ***

The hounds of Tindalos

Download Formats:

Excerpt

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Weird Tales March 1929.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

"I'm glad you came," said Chalmers. He was sitting by the window and

his face was very pale. Two tall candles guttered at his elbow and cast

a sickly amber light over his long nose and slightly receding chin.

Chalmers would have nothing modern about his apartment. He...

Read the Full Text

— End of The hounds of Tindalos —

Book Information

- Title

- The hounds of Tindalos

- Author(s)

- Long, Frank Belknap

- Language

- English

- Type

- Text

- Release Date

- May 8, 2024

- Word Count

- 5,321 words

- Library of Congress Classification

- PS

- Bookshelves

- Browsing: Literature, Browsing: Science-Fiction & Fantasy, Browsing: Fiction

- Rights

- Public domain in the USA.

Related Books

Famous stories from foreign countries

English

494h 26m read

The incredible slingshot bombs

by Williams, Robert Moore

English

96h 4m read

The eater of souls

by Kuttner, Henry

English

22h 19m read

Maehoe

by Leinster, Murray

English

115h 53m read

The air splasher

by Watkins, Richard Howells

English

138h 53m read

Hooking a sky ride

by Morrissey, Dan

English

37h 54m read