The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Intimate Letters of Hester Piozzi and

Penelope Pennington, 1788-1821, by Hester Lynch Piozzi and Penelope Sophia Weston Pennington

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: The Intimate Letters of Hester Piozzi and Penelope Pennington, 1788-1821

Author: Hester Lynch Piozzi

Penelope Sophia Weston Pennington

Editor: Oswald Greenwaye Knapp

Release Date: April 19, 2018 [EBook #57003]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE INTIMATE LETTERS ***

Produced by MWS, Karin Spence, and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

THE INTIMATE LETTERS OF HESTER

PIOZZI & PENELOPE PENNINGTON

1788-1821

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

AN ARTIST'S LOVE STORY

[Illustration: _M^{rs}. Hester Lynch Piozzi._

_Engraved by H. Meyer_,

_from an original Drawing by J. Jackson._]

THE INTIMATE LETTERS OF

HESTER PIOZZI AND PENELOPE

PENNINGTON 1788-1821

EDITED BY OSWALD G. KNAPP

WITH THIRTY ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON: JOHN LANE, THE BODLEY HEAD

NEW YORK: JOHN LANE COMPANY

TORONTO: BELL & COCKBURN. MCMXIV

Printed by BALLANTYNE, HANSON & CO.

at the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh

TO

MY WIFE

PREFACE

The letters included in this volume have been printed without

alteration, except that some of Mrs. Piozzi's redundant initial

capitals have been suppressed, and that her somewhat erratic

punctuation has been, to a certain extent, systematised. Her spelling,

save for the correction of obvious slips, which are very rare, has not

been altered. The omitted passages, which have been indicated wherever

they occur, mainly consist of formal "compliments" at the beginning

or end of letters, to which she was much addicted, unsavoury medical

details, or casual allusions to insignificant persons and trivial

events of no interest in themselves, and having no direct bearing on

the story of her life.

For the outline of her career before her second marriage I have

to acknowledge my indebtedness to previous writers, particularly

Hayward and Mangin, and the more recent works of Mr. Seeley and

Messrs. Broadley and Seccombe; not forgetting the indispensable

_Dictionary of National Biography_, for the identification of many

persons incidentally mentioned. I have also to express my thanks to

Miss Thrale of Croydon for interesting information respecting her

family; and above all to Mr. A. M. Broadley, not only for his generous

permission to make use of Mrs. Piozzi's unpublished Commonplace Book,

now in his possession, but also for allowing me to draw freely upon

his unrivalled collection of prints, &c., relating to this period,

from which the greater part of the illustrations has been taken.

INWOOD, PARKSTONE,

_July 1913_.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I

PAGE

Introductory--Mrs. Piozzi and the blue-stockings--Penelope

Weston--The Salusbury family--Early years and

education--Marriage to Thrale, 1763--Widowhood--Marriage to

Piozzi, 1784--Foreign travel--Return to England, 1788 1

CHAPTER II

The Piozzis in Hanover Square--Scotch tour, 1789--Visit to

Wales--Return to Streatham Park, 1790--Harriet Lee's

romance--Nuneham and Mrs. Siddons, 1791--French

Revolution--Cecilia's admirers--Apprehensions for Cecilia--The

September massacres--Miss Weston's engagement 18

CHAPTER III

Miss Weston marries Wm. Pennington, 1792--Execution of

Louis XVI--Reconciliation of Mrs. Piozzi and her daughters,

1793--Irish Rebellion--_British Synonymy_--Fleming's

prophecies--Cecilia's flirtations--Residence at Denbigh,

1794--Building of Brynbella 73

CHAPTER IV

Cecilia's engagement and marriage to Mostyn, 1795--Her

dangerous illness--Friction with the Mostyns--Disturbances

in Italy and Ireland--Death of Maria Siddons--Visit

to Bath, 1798 121

CHAPTER V

Adoption of John Salusbury Piozzi--The _Canterbury Tales_--Bath

Riots, 1800--Chancery suit with Miss Thrale--Bach-y-graig

restored--_Retrospection_ published, 1801--The Blagdon

controversy--Political epigram 169

CHAPTER VI

Attacks by reviewers--The Peace, 1801--Visit to London--South

Wales--Mrs. Pennington's troubles--Bath again--Breach

with Mrs. Pennington, 1804 218

CHAPTER VII

Renewal of friendship, 1819--Weston-super-Mare--W. A.

Conway--Birthday fête, 1820--Conway's love affair--Penzance--The

Queen's trial--More law--Land's End--Return to Clifton

and death, 1821--Mrs. Pennington's obituary notice--Her

relations with the daughters and the executors--Epitaph 270

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

MRS. PIOZZI (_Photogravure_) _Frontispiece_

_By_ Meyer, _after_ Jackson, 1811, _from the Collection of_

A. M. Broadley, Esq.

TO FACE PAGE

CATHERINE OF BERAIN 7

_By_ W. Bond, _after_ J. Allen, 1798.

SIR RICHARD CLOUGH 8

_By_ Basire, _after_ M. Griffith.

DR. JOHNSON'S BIOGRAPHERS (MRS. PIOZZI, CAREY?, AND BOSWELL) 16

_From a caricature_, 1786, _in the Collection of_ A. M.

Broadley, Esq.

STREATHAM PARK 28

_By_ J. Landseer, _after_ S. Prout, _from the Collection

of_ A. M. Broadley, Esq.

ANNA SEWARD 34

_By_ W. Ridley, _after_ Romney, 1797, _from a print in

the British Museum_.

HELEN MARIA WILLIAMS 44

_From an engraving by_ J. Singleton, _in the British Museum_.

MRS. THRALE AT THE AGE OF FORTY 58

_From the original picture by_ Sir Joshua Reynolds,

_about_ 1781.

MRS. SIDDONS 70

_By_ R. J. Lane, _after_ Sir Thos. Lawrence.

MARIA SIDDONS 80

_By_ G. Clent, _after_ Sir Thos. Lawrence.

SARAH MARTHA SIDDONS 89

_By_ R. J. Lane, _after_ Sir Thos. Lawrence.

MRS. PIOZZI 95

_From an engraving by_ Dance, 1793, _from the Collection

of_ A. M. Broadley, Esq.

ARTHUR MURPHY 107

_From a print in the Collection of_ A. M. Broadley, Esq.

CECILIA MOSTYN 126

_From the Collection of_ A. M. Broadley, Esq.

ELIZA (FARREN) COUNTESS OF DERBY, 1797 141

_From a print in the British Museum._

CECILIA SIDDONS 144

_By_ R. J. Lane, _after_ Sir Thos. Lawrence.

JOSEPH GEORGE HOLMAN 150

_By_ W. Angus, _after_ Dodd, 1784, _from a print in the

British Museum_.

SOPHIA LEE 160

_By_ Ridley, _after_ Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1809, _from

the Collection of_ A. M. Broadley, Esq.

MRS. PIOZZI (ABOUT 1800) 180

_By_ M. Bovi, _after_ P. Violet, 1800, _from the

Collection of_ A. M. Broadley, Esq.

BACH-Y-GRAIG HOUSE IN 1776 199

_By_ Godfrey, _after_ J. Hooper, 1776.

HANNAH MORE 228

_By_ Scriven, _after_ Slater, 1813, _from the

Collection of_ A. M. Broadley, Esq.

MRS. PIOZZI (ABOUT 1808) 250

_By_ J. Bate, _after a medallion by_ Henning, 1808,

_from the Collection of_ A. M. Broadley, Esq.

WILLIAM AUGUSTUS CONWAY AS HENRY V 280

_By_ Rivers, _after_ De Wilde, 1814, _from the Collection

of_ A. M. Broadley, Esq.

THE LOWER (KINGSTON) ROOMS, BATH 296

_By_ W. J. White, _after_ H. O. Neill, _from the

Collection of_ A. M. Broadley, Esq.

PROGRAMME OF MRS. PIOZZI'S CONCERT, 1820, WITH MS. NOTES. 299

_By_ Mrs. Pennington _and_ Maria Brown

MISS FELLOWES AS HERB STREWER AT THE CORONATION OF GEO. IV, 314

1821

_By_ M. Gauci, _after_ Mrs. Baker, _from the Collection

of_ A. M. Broadley, Esq.

"FRYING SPRATS" AND "TOASTING MUFFINS" 342

_From a caricature by_ Gillray, 1791, _in the Collection

of_ A. M. Broadley, Esq.

TICKET FOR MRS. PIOZZI'S FÊTE 355

THE BURNING OF THE KINGSTON ROOMS 355

_From a ball ticket, 1821, in the Collection of_

A. M. Broadley, Esq.

THOMAS SEDGWICK WHALLEY, D.D. 376

_By_ J. Brown, _after_ Sir Joshua Reynolds, _from a print

in the Collection of_ A. M. Broadley, Esq.

THE INTIMATE LETTERS OF HESTER

PIOZZI & PENELOPE PENNINGTON

1788-1821

THE INTIMATE LETTERS OF HESTER PIOZZI & PENELOPE PENNINGTON

CHAPTER I

Introductory--Mrs. Piozzi and the blue-stockings--Penelope

Weston--The Salusbury family--Early years and

education--Marriage to Thrale, 1763--Widowhood--Marriage to

Piozzi, 1784--Foreign travel--Return to England, 1788.

In the course of the last hundred years the horizon of woman's work

and interests has been extended so widely, and in so many directions,

religious, educational, political, economic, and social, that already

the Blue-Stockings of the eighteenth century seem almost as far

removed from us as the Précieuses Ridicules of Molière. The student of

the period takes note of them as products of a social and intellectual

movement characteristic of their day; and the general reader knows a

few of them by name, though chiefly as satellites revolving round the

greater luminaries of the age: but their works are, for the most part,

unread and forgotten. This is not, perhaps, a matter for surprise,

seeing that they were not profound or original thinkers, and even

their works of fiction are too stilted and prolix for our impatient

age. Indeed their contemporaries were probably less impressed by the

learning, even of the leaders of the movement, than by their brilliant

conversational powers, in which, perhaps, they have never been

surpassed; though this is a matter on which, from the nature of the

case, we have, for the most part, but imperfect materials with which

to form a judgment.

If there be an exception, it is to be found in the case of the writer

of the following letters. Of the literary society in which she moved

she was an acknowledged queen, who hardly yielded precedence on her

own ground to Mrs. Montagu herself. Indeed Wraxall was of opinion that

she possessed "at least as much information, a mind as cultivated, and

even more brilliancy of intellect"; while Madame D'Arblay thought that

her conversation was "more bland and more gleeful" than that of either

Mrs. Montagu or Mrs. Vesey. "To hear you," wrote Boswell (before their

great quarrel), "is to hear Wisdom, to see you is to see Virtue." It

may be said that this was merely the partiality of friendship, or

an example of the mutual admiration which was rather characteristic

of the coterie. But Anna Seward, who roundly condemned her literary

style, declared that her conversation was "the bright wine of

intellect, which has no lees"; and the great Lexicographer himself,

who was not wont to be unduly lavish of his praises, vouchsafed on one

occasion to tell her that she had "as much wit, and more talent," than

any woman he knew. And what is still more remarkable, her power of

pleasing continued, with but little diminution, to the end of her long

life. Sir William Pepys, who had known her for many years, writing

after her death, says he had "never met any human being who possessed

the talent of conversation to such a degree."

And more easily than in the case of most of her contemporaries, the

charm of her conversation can be gathered from her letters. To it

Fanny Burney's criticism seems to apply as fitly as to the record

of her Italian tour, of which it was originally written: "How like

herself, how characteristic is every line! wild, entertaining,

flighty, inconsistent, and clever!" The spontaneity and freshness of

her style is the more remarkable when we remember the taste of the

circle in which she moved, and compare her letters with the laboured

and formal productions of her friend Anna Seward, the much-admired

"Swan of Lichfield," and particularly when we recall her intimate

relations with Johnson for a period of nearly twenty years. The fact

is that he found her mind already formed, and though it was for a time

"swallowed up and lost," as she says, in his vast intellect, it was

not absorbed, but emerged later on, strengthened and clarified indeed,

but with its original characteristics little changed.

A good many of her letters have already seen the light. Those written

to Dr. Johnson she herself published after his death. Her friend,

the Rev. Edward Mangin, included about thirty, written for the most

part to himself, in his _Piozziana_; while Hayward, in the so-called

_Autobiography_, gives about a hundred and forty, of which a few

were written to the brothers Lysons, and nearly all the remainder to

Sir James Fellowes. But these differ in some important respects from

those in the present volume. They were nearly all written to men, and

though they may possibly be somewhat more brilliant, and make rather a

greater show of learning, they are hardly so frank and unaffected, and

do not reveal the personality of the writer so clearly as those which

she wrote to an intimate friend of her own sex; in whose case she had

no temptation to pose, even unconsciously, nor any lurking thought of

a reputation as a wit to be kept up.

Their recipient was fully alive to their importance, and in a letter

in Mr. Broadley's collection, dated 1821, quotes her as saying that

she had "a larger and perhaps better collection of dear Mrs. Piozzi's

letters than any other correspondent." And she backs her opinion by

that of Dr. Whalley, who had probably seen most of them, to the effect

that "was any publication intended, they would be a most rich and

valuable addition, and altogether form a collection of letters more

eagerly sought after, and more agreeable to the general public than

any that have been ever published."

The letters in question, some two hundred in number, begin in 1788,

not long after Mrs. Piozzi's second marriage, and continue (though

with a break of fifteen years) to within a few days of her death in

1821. The friend to whom they were written first appears on the scene

as Penelope Sophia Weston, a friend of Mrs. Siddons, Helen Williams,

and Anna Seward, whose published letters contain many addressed to

"the graceful and elegant Miss Weston," who was then the leading

spirit of "a knot of ingenious and charming females at Ludlow in

Shropshire," where Anna paid her a visit in 1787. She was then living

with her widowed mother, who had not much in common with the literary

proclivities of her daughter. She writes in 1782: "My mother is a very

good woman, but our minds are, unfortunately, cast in such different

moulds--our pursuits and ideas on every occasion are likewise so--that

it is of very little moment our speaking the same language. Indeed I

see very little of her; for she is either busied in domestic matters,

praying, gardening, or gossiping most part of the day; while I sit

moping over the fire with a book or pen in my hand, without stirring

(if the weather is unfavourable), for weeks together.... Remember me

to your charming Mrs. Siddons." This passage appears in the published

correspondence of her "dear cousin Tom," the Rev. T. S. Whalley, D.D.,

who was not, strictly speaking, related to her at all, but had married

her first cousin, Miss Jones of Longford. As he had a house at Bath he

may have been the means of making her acquainted with Mrs. Piozzi.

It does not fall within the scope of this work to give a detailed

account of Mrs. Piozzi's life: this has been done, though in a

somewhat piecemeal manner, by A. Hayward,[1] and more recently by

Mr. H. B. Seeley.[2] But for the better understanding of the letters

it will be necessary to give a brief outline of her career up to

the date at which they begin; and this may fitly be preceded by some

account of her family, a matter in which she was keenly interested,

and to which she frequently recurs in her correspondence.

[1] _Autobiography, Letters, and Literary Remains of Mrs. Piozzi_, 2

vols., 1861.

[2] _Mrs. Piozzi: a Sketch of her Life, and Passages from her Diaries,

Letters, &c._, 1891.

Mrs. Piozzi was the last of an old knightly Welsh family, Welsh by

long residence, if not by blood, called in the early records Salbri

or Salsbri, and Englished as Salesbury or Salisbury, and in more

recent times as Salusbury. It produced a goodly number of soldiers,

scholars, and divines; the latter chiefly in a younger branch seated

at Rûg in Merioneth in the sixteenth century. Among these were William

Salesbury, "the best scholar among the Welshmen," who compiled a Welsh

dictionary, and made the first translation of the New Testament into

that language; Henry Salesbury, a noted doctor and grammarian, and

John Salesbury, a Jesuit, Superior of the English Province. In the

same century the elder or Llewenny line boasted of John Salesbury, a

Benedictine monk who forsook his vows and married, but was made by

Queen Elizabeth Bishop of Sodor and Man; Foulke Salesbury, first Dean

of St. Asaph, and Thomas Salesbury, who was executed for his share in

Babington's Plot.

In the course of centuries a goodly number of romantic legends had

attached themselves to the earlier generations, particularly in

connection with their armorial bearings, in which Mrs. Piozzi was

an enthusiastic believer. As far back as the sixteenth century the

Salesburys had claimed as their eponymous ancestor a certain Adam,

believed to be a younger son of Alexander, Duke of Bavaria, hence

known as Adam de Saltzburg, who made his way to England, and was

appointed by Henry II Captain of the castle of Denbigh. Another

and less probable version of the story, favoured by Mrs. Piozzi,

makes him a follower of William the Conqueror, and gives him a fair

estate in Lancashire, on which he built a seat called Saltsbury or

Salisbury Court. Of her descent from this Adam she says: "I showed

an abstract to the Heralds in Office at Saltzburg, when there, and

they acknowledged me a true descendant of their house, offering me all

possible honours, to the triumphant delight of dear Piozzi, for whose

amusement alone I pulled out the Schedule." This may be satisfactory

evidence for the existence of Adam, but of course the Heralds had

to take the descent on trust. The fact appears to be that Adam of

Llewenny was an Englishman who settled in Wales after its conquest

at the end of the thirteenth century, and was a member of the family

of Salesbury of Salesbury, co. Lancs. Adam's descendant, Sir Henry

Salesbury "the Black," "having taken three noble Saracens with his

own hand on the first Crusade, Cœur de Lion knighted him on the

field of battle, and to the old Bavarian lion which adorned his shield

added three crescents." This Henry is supposed to have built Llewenny

Hall. The name of another Henry, who fought in the Wars of the Roses,

"stood recorded on a little obelisk, or rather cippus, by the roadside

at Barnet, ... so long that I remember my father taking me out of

the carriage to read it, when I was quite a child. He had shown

mercy to an enemy on that occasion, who, looking on his device ...

flung himself at his feet with these words--'SAT EST PROSTRASSE

LEONI.' Our family have used that Leggenda as motto to the coat

armour ever since." The arms of the present Piozzi-Salusbury family

are: Gules, a lion rampant argent, ducally crowned or, between three

crescents of the last, a canton ermine, with motto as above.

We are on firmer ground when we arrive at Sir John Salesbury of

Llewenny, Kt., M.P. for Denbigh in the sixteenth century, and his

family of fourteen children, of whom the eldest and youngest sons

were the ancestors of Mrs. Piozzi on the maternal and paternal side

respectively. John, the eldest, married Catherine of Berain, a lady

who deserves a paragraph to herself. Their grandson, Sir Henry

Salusbury of Llewenny, was created a Baronet by James I, but this

line came to an end with his granddaughter Hester, who married Sir

Robert Cotton of Combermere Abbey, co. Chester, Bart., ancester of

Lord Combermere. Their granddaughter, Hester Maria Cotton, was Mrs.

Piozzi's mother.

[Illustration: CATHERINE OF BERAIN

_By W. Bond after J. Allen, 1798_]

Catherine of Berain above mentioned, called from her numerous

descendants Mam y Cymry, or Mam Gwalia, "Mother of Wales," was a

great-granddaughter of Fychan Tudor of Berain, a personage claimed by

Mrs. Piozzi, though not acknowledged by the genealogists, as a younger

son of Sir Owen Tudor, Kt., by Queen Catherine, widow of Henry V.

That the Mother of Wales (who would, on this hypothesis, be a cousin

of Queen Elizabeth) was a lady of great attractions, both in person

and in purse, may be gathered from the story of her four matrimonial

ventures, which cannot be better told than in the words of Pennant,

the historian and naturalist, who was himself one of her descendants.

"The tradition goes that at the funeral of her beloved spouse (Sir

John Salesbury), she was led to Church by Sir Richard (Clough), and

from Church by Morris Wynn of Gwydyr, who whispered to her his wish

of being her second. She refused him with great civility, informing

him that she had accepted the proposal of Sir Richard on her way to

Church; but assured him--and was as good as her word--that in case she

performed the same sad duty, which she was then about, to the Knight,

he might depend on being her third. As soon as she had composed this

gentleman, to show that she had no superstition about the number

three, she concluded with Edward Thelwall of Plas y Ward, Esq.,

departed this life Aug. 27, and was interred at Llanivydd on the 1st

of Sep. 1591."

For the paternal ancestry of Mrs. Piozzi we must return to Roger, the

youngest son of Sir John Salesbury, M.P. He married Anne, one of the

daughters of Catherine of Berain by her second husband, Sir Richard

Clough, Kt., another picturesque figure who deserves a separate

mention. He was the youngest son of a Denbigh glover, who became a

prosperous merchant, and was a partner of Sir Thomas Gresham, whom he

assisted to found the Royal Exchange, and whose continental business

he superintended. This necessitated a residence at Antwerp, where he

also acted as a kind of unofficial agent of the English Government.

His mercantile pursuits were not, however, so absorbing but that he

could make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, where he was made a Knight of

the Holy Sepulchre, and thereafter bore the five crosses of Jerusalem

in his arms. During one of his brief visits to England, about 1567,

he married, as we have seen, Catherine of Berain, then widow of Sir

John Salesbury of Llewenny, and began building two mansion-houses, one

called Plas Clough and the other Bach-y-graig, both in Flintshire, and

both in the Dutch style, perhaps by means of imported workmen. The

former was inherited by his son Richard, by a former wife, an Antwerp

lady named Van Mildurt, whose descendants still possess it. The latter

he bequeathed to Anne Salesbury, one of his daughters by Catherine of

Berain. It thus became the seat of the younger line of the family down

to the time of John Salusbury, Mrs. Piozzi's father, and came to her

on the death of her parents.

Mrs. Piozzi herself was born 16th January 1740 (Old Style), or 27th

January 1741 (New Style), at Bodvel, near Pwllheli, and was christened

Hester Lynch, the names being derived from her mother, Hester Maria

Cotton (granddaughter of Hester Salusbury, the last of the elder

line), and from her maternal grandmother, Philadelphia, daughter of

Sir Thomas Lynch. Her father, John Salusbury of Bach-y-graig, left

an orphan at four years old, was high-spirited and attractive, but

careless and extravagant, and even before his marriage had succeeded

in heavily encumbering his property. His wife's fortune of £10,000

barely sufficed to pay his debts and to provide a modest cottage in

which to start housekeeping. Before long she and her only child found

a more comfortable abode at Llewenny Hall with her eldest brother,

Sir Robert Salusbury Cotton, who took a great liking for little

Hester, and being himself childless, promised to provide for her; but

his sudden death before he had carried out his intention left them

in great straits. John Salusbury had been sent out by Lord Halifax

to assist in re-settling the colony of Nova Scotia, but it was not a

lucrative employment, and his wife sought a home for her child first

at East Hyde, Beds., with her own mother, Philadelphia, then the widow

of Captain King, and afterwards at Offley Hall, Herts., the seat of

her brother-in-law, Sir Thomas Salusbury, Judge of the Admiralty Court.

[Illustration: SIR RICHARD CLOUGH

_By Basire after M. Griffith_]

So far Hester's education had been of a very desultory kind, though

she had been well grounded in French by her parents from a very early

age. At East Hyde she learnt to love and manage horses, startling,

and somewhat shocking her grandmother, by driving two of the "ramping

warhorses" who drew the family coach round the courtyard. But her

first systematic instruction she received at Offley, where she

learnt Italian and Spanish, apparently from her uncle's wife, Anna,

daughter of Sir Henry Penrice, and "Latin, Logic, Rhetoric, &c." from

a Doctor Collier, for whom she had a warm regard, and who did more,

she considered, to form her mind than anyone with whom she afterwards

came in contact, Johnson not excepted. Greek she did not learn from

him, for she laments her ignorance of it some years later, when, in

the course of her Italian tour, she was unable to read an inscription

in that language which was shown to her. So Mangin was no doubt

unconsciously exaggerating when he wrote that she had "for more than

sixty years ... studied the Scriptures ... in the original languages."

But it seems fairly certain that she acquired some knowledge of Greek,

and possibly also of Hebrew, in later life, though she makes no parade

of her acquirements. The stray words in these languages which are

found in her letters are not conclusive evidence, as they may have

been merely copied from some work which she had been reading. But in

her Commonplace Book, now in the possession of Mr. A. M. Broadley, and

written only for her own amusement, occur several Greek phrases, and

an epigram of some length, with a translation, apparently her own. And

it is noteworthy that the Greek is written with the breathings and

accents, in the clear, firm hand of one well used to the script, very

unlike the tentative efforts of a beginner.

By this time suitors for the hand of the prospective heiress began to

arrive, among whom was Henry Thrale, proprietor of a lucrative brewery

in Southwark, who commended himself to the uncle as being a "thorough

sportsman," and to the mother by his assiduous attentions to herself.

But he does not appear to have taken the trouble to be more than

barely civil to the bride elect, who naturally resented his attitude,

and heartily disliked the idea of a marriage with him. She appealed to

her father, who had now returned from America, having no aptitude or

liking for a colonial career, and who sympathised with her feelings,

but his sudden death in 1762 put an end to any hope of intervention

on his part. Her mother and uncle pressed on what they considered a

desirable match, and she was married to Thrale, 11th October 1763.

At this period, at any rate, Henry Thrale was by no means the dull,

heavy, self-indulgent being that some accounts of him in later life

might seem to suggest. His father, Ralph Thrale, a shrewd, self-made

man, used the fortune he had amassed at the Old Anchor Brewery to

give his son the best education the period could afford. Much of his

boyhood he spent at Stowe in Buckinghamshire, where his associates

belonged to a group of great county families; for Ralph Thrale's

cousin, Ann Halsey, had married Sir Richard Temple of Stowe, created

Viscount Cobham, whose sisters had married into the families of

Grenville and Lyttelton. As some of them were indebted to the father,

motives of policy may have had something to do with their friendship

for the son. At the age of fifteen he was sent to Oxford, which he

left without taking a degree, though he was afterwards created a

D.C.L. Then he was sent on the grand tour, on an allowance of £1000

a year, with William Henry Lyttelton, afterwards Lord Westcote and

Lyttelton, whose expenses were also paid by the elder Thrale, and

at the time of his marriage he was a finished "man about town."

His artistic and literary tastes are indicated by the gallery of

portraits by Reynolds which he formed at Streatham Park, and by the

literary society he loved to entertain there, from Johnson downwards.

The latter spoke of him as "a real scholar," and said that "if he

would talk more, his manner would be very completely that of a

perfect gentleman"; and he had, what Johnson entirely lacked, a keen

appreciation of natural scenery. His religious and moral principles

might be expected to be those of his associates, who at the time of

his marriage, with the exception of one Romanist, all seemed to his

wife to be professed infidels. But his outward conduct was at least

decorous, and she remarks that his conversation was wholly free from

all oaths, ribaldry, and profaneness. In 1779 she wrote in _Thraliana_

(her private diary): "Few people live in such a state of preparation

for eternity, I think, as my dear Master has done since I have been

connected with him: regular in his public and private devotions,

constant at the Sacrament, temperate in his appetites, moderate in his

passions,--he has less to apprehend from a sudden summons than any man

I have known who was young and gay, and high in health and fortune."

Their usual residence was a pleasant country house known as Streatham

Park, standing in grounds of about a hundred acres, but in winter

she was expected to live at his business premises in Deadman's

Lane, Southwark, a stipulation which had put an end to several of

Thrale's previous matrimonial negotiations. Her acceptance of it she

believed to have been the determining factor in his final choice of

a wife. He possessed also a hunting-box near Croydon, where he kept

a pack of hounds, and a house in West Street, Brighton. But with all

the comfort, and even luxury of her surroundings, she enjoyed no

confidence and little sympathy from her husband. He required a wife

to do the honours of his table and to bear his children; other forms

of activity were frowned upon or banned. Riding to hounds was too

masculine to be tolerated; she was not permitted to have any voice in

the management of her household, and she did not even know what there

was for dinner till it appeared on the table. She was not allowed to

know anything of his business affairs till a serious crisis occurred,

when she saved the situation by her promptitude in raising some

£20,000 from relatives and friends to meet pressing demands. This, and

her energetic canvassing of Southwark when Thrale was standing for

Parliament, seems to have convinced her husband of her capabilities,

and to have generated in him a certain amount of respect, if not of

affection.

The sphere of her activities being thus restricted, and having no

taste for gay society, she was driven to occupy herself with her books

and her children, of whom she had twelve, though only four survived

their childhood. While still in her teens she had contributed verses

anonymously to the _St. James' Chronicle_, but at this period she

probably had little opportunity and no encouragement to practise

composition. Thrale, however, was interested in men of letters, and

the introduction of Johnson to Streatham Park in 1764 helped to make

it a meeting-place for many literary and artistic celebrities, such

as Murphy, Reynolds, the Burneys, the Sewards, and others. Johnson

himself came to be looked upon as one of the family, having a room

reserved for him at Streatham and Southwark, and accompanying them

as a matter of course on their visits to Bath and Brighton, and on

longer expeditions to Wales in 1774 and to Paris the following year.

Thrale retired from Parliament in 1780, and died 4th April 1781, of

apoplexy, largely the result of over-indulgence at table, to which in

his later years he had become addicted. Both his sons had predeceased

him, Henry, the elder, in 1766, and Ralph in 1775; and his widow was

left with five daughters, all under age. Harriet, the youngest of

these, died at school in 1783, shortly before Mrs. Thrale's second

marriage; the four survivors were as follows.

Hester Maria, born 1762, known in her childhood as Queeny, a name

given her by Dr. Johnson, who supervised her education, and with whom

she was a great favourite. She inherited much of her father's strong,

but cold and reserved character, and was never on very affectionate

or sympathetic terms with her mother. She married at Ramsgate, 10th

January 1808, Admiral Lord Keith, G.C.B., then a widower, son of the

tenth Lord Elphinstone, and who was created Viscount Keith in 1814.

She died at 110 Piccadilly, 31st March 1857, leaving an only daughter,

the Hon. Augusta Henrietta Elphinstone, who married twice, but left no

issue.

Susannah Arabella, born 1770; who died unmarried at Ashgrove,

Knockholt, 5th November 1858, and was buried at Streatham.

Sophia, born 23rd July 1771; who married, 13th August 1807, Henry

Merrick Hoare, son of Sir Richard Hoare of Barn Elms, Bart. She died

at Sandgate, 8th November 1824, leaving no issue, and was buried at

Streatham.

Cecilia Margaretta, born 1777. She married, 1795, John Meredith Mostyn

of Segrwyd, who died 19th May 1807. She survived him half a century,

dying at Sillwood House, Brighton, 1st May 1857. They had three

sons, of whom the eldest was christened John Salusbury, but all died

unmarried.

Her widowhood, 1781-4, was the most stormy period of Mrs. Piozzi's

life. Her first anxiety was to dispose of the brewery, which neither

she nor the executors felt competent to carry on. After some

negotiation it was purchased by the Barclays for £135,000, and so

provided a respectable portion for each of the girls. Bach-y-graig,

her ancestral abode, had come to her on the death of her mother, and

Thrale had left her Streatham Park for life, but the one was ruinous

and the other expensive, and on the score of economy she determined to

let Streatham and live at Bath. This course also had the advantage--in

her eyes at least--of removing her somewhat farther from Johnson's

sphere of influence. His eccentric habits and domineering temper had

for many years been somewhat of a trial to her, though delight in his

conversation, admiration for his talents, and regard for his character

had hitherto induced her to bear them with patience. She was anxious

to avoid a rupture with him, but it was more than probable that, both

as an old friend and as one of her husband's executors, he would

strongly disapprove of the second marriage which she was now beginning

to contemplate with Signor Gabriel Piozzi, an Italian musician and

singer.

He had been recommended to her in 1780 as a man "likely to lighten

the burden of life to her, and just a man to her natural taste," by

Fanny Burney; but it is recorded that on the first occasion on which

they met in company, when he played and sang at Dr. Burney's in 1777,

Mrs. Thrale stood behind him as he sat at the piano, and mimicked his

gestures and manner, to the mingled amusement and embarrassment of

the company. From this unpromising beginning grew a friendship which

gradually ripened into love, and in 1783 it was apparent that Piozzi

was seriously courting the widow, and that she was not ill-disposed to

his suit. Then the storm burst. Mrs. Thrale was in no sense a public

character, but she was violently attacked in the public prints, which

had previously amused themselves by announcing her engagement to

Crutchley, to Seward, and even to Johnson himself. Her friends were

horror-struck, and remonstrated each after their kind. Johnson went

so far at last as to charge her with abandoning her children and her

religion, and with forfeiting both her fame and her country. But, as

might be expected, her worst foes were those of her own household,

and the opposition of her children, and more particularly of Hester,

was the hardest thing she had to bear. It is somewhat difficult for

us who are so far removed from the controversy to grasp the reason

of all this outcry. But it must be remembered that Piozzi was a

Papist, a foreigner, and a singer, a combination which to the average

Englishman of the eighteenth century meant an untrustworthy and

contemptible mountebank. The irony of the situation was that Piozzi

met with similar objections from his own family, who were scandalised

at his proposed alliance with a heretic, and could not conceive that

a brewer's widow could be a lady, or a fit mate for a member of an

old and well-connected family. Years afterwards, when Cecilia was

travelling on the Continent, she made the acquaintance of the Piozzis,

and wrote that she "liked them above all people, if only they were not

so proud of their family." "Would not that make one laugh two hours

before one's death?" is her mother's comment in 1818.

For some time she held out, but at last the combined opposition was

too much for her; Piozzi was dismissed, gave up her letters, and

went abroad. But the strain was too great, her health gave way, and

her physician, considering her condition serious, recommended that

Piozzi should be recalled, as the only hope of saving her life. Miss

Thrale reluctantly acquiesced, and they were shortly afterwards

married in London, according to the Roman rite, on 23rd July, and

in St. James' Church, Bath, on 25th July, 1784. From this date her

worst troubles were over, and she entered on what she describes as

twenty years of unalloyed happiness. Having made what she considered

suitable arrangements for her daughters, by providing a trustworthy

companion for Miss Thrale, and placing the younger ones in a school

at Streatham, she started, with her husband, on a long-projected

Italian tour. Hayward says that Cecilia accompanied them, but this is

contradicted by Mrs. Piozzi's own statements in the _Autobiography_.

They had not long left England when Miss Thrale removed her sisters to

another school, dismissed her companion, and retired with an old nurse

to the Brighton house, where she shut herself up and spent her time in

the study of Hebrew and mathematics. Shortly afterwards, on coming of

age, she rented a house in town, and took her younger sisters to live

with her.

Meantime the Piozzis travelled via Paris, Lyons, Turin, and Genoa

to Milan, where they wintered, being everywhere well received both

by Italian friends and by the English colony, including the Duke

and Duchess of Cumberland; a fact which probably had a good deal to

do with the attitude of society at home on their return to England.

The following summer they spent at Florence in the company of

Merry, Greatheed, and the other Della Cruscans, to whose _Florence

Miscellany_, published in 1785, she contributed some verses. Her

literary instincts, long repressed, were at last encouraged, and

Johnson being now dead she compiled at Leghorn in 1786 her _Anecdotes

of Dr. Johnson during the last twenty years of his Life_; much to

the annoyance of Boswell, who regarded everything relating to his

hero as his own peculiar preserve, and resented her refusal to add

her reminiscences to Johnson's Pyramid, as he styled his own great

work. The book, for which she got £300, was well received, the whole

edition being sold out in three days, and four editions appeared the

same year; but Boswell's strictures on her alleged inaccuracy led to a

lively "Bozzy and Piozzi" controversy, with accompanying caricatures,

which amused the town, and doubtless helped to keep the author in

the public eye. The Piozzis returned to England through Germany in

1787, and lived for a time in Hanover Square with Cecilia, the elder

daughters at first keeping aloof, though they often met in public. But

society had forgiven her if her children had not, and sooner or later

the old friends who had protested most loudly took the opportunity of

making their peace.

[Illustration: DR. JOHNSON'S BIOGRAPHERS (MRS. PIOZZI, CAREY? AND

BOSWELL)

_From a caricature, 1786, in the Collection of A. M. Broadley, Esq._]

About this time, as it would seem, she made the acquaintance of Miss

Weston, now about thirty-six years of age, who had moved with her

mother from Ludlow to London, and was living with a relative in Queen

Square, Westminster, and therefore not far from the Piozzis. A letter

she wrote to Dr. Whalley in 1789 shows that she was then in charge of

a young pupil, with whom she had but little in common, as the girl was

interested in nothing but dress. She adds that the kindness of dear

Mrs. Piozzi towards her, on all occasions, exceeds all expression.

CHAPTER II

The Piozzis in Hanover Square--Scotch tour, 1789--Visit

to Wales--Return to Streatham Park, 1790--Harriet

Lee's romance--Nuneham and Mrs. Siddons, 1791--French

Revolution--Cecilia's admirers--Apprehensions for Cecilia--The

September massacres--Miss Weston's engagement.

In July 1788 the Piozzis took rooms at Exmouth, from which they had

views "of sea and land, Lord Courtney's fine seat and Lord Lisburne's

pretty grounds all facing us." But though there was "a very pretty

little snug society" there, Mrs. Piozzi votes it "a dull place,"

where "if one is idle, one is lost." Idleness, however, was not one

of her failings. Early in the year she had published her _Letters to

and from the late Samuel Johnson, LL.D._, which made £500, and had

a large sale. Some allusions in the correspondence, more truthful

than complimentary, to Joseph Baretti, who had at one time acted as

tutor to Miss Thrale at Streatham, roused him to make a coarse and

violent attack upon her in the _European Magazine_, which caused her

much pain. He also satirised her in a farce entitled _The Sentimental

Mother_, in which she figures as Lady Fantasma Tunskull, and her

husband as Signor Squalici. Yet she forgave him, and when he died in

the following year, sent a kindly notice of him to the _World_. This

year too, as she records in her Commonplace Book, she wrote a dramatic

masque called _The Fountains_, which was much admired by Miss Farren,

and which Sheridan and Kemble "pretended to like exceedingly," but

contrived to lose the copy. She adds: "It has often been in my head

to publish it with other poems--but 'tis better let that alone."

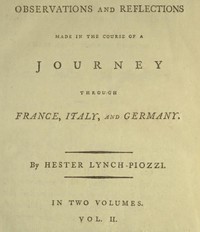

About this time she must have been engaged on a more ambitious task,

the record of her continental tour, which appeared in 1789 under the

title of _A Journey through France, Italy, and Germany_. This was well

received by the general public, though some of the Blue-Stockings

objected to its colloquial style. Anna Seward, for instance, gently

reproved "the pupil of Dr. Johnson" for "polluting with the vulgarisms

of unpolished conversation her animated pages," and wrote as follows

to Miss Weston, who defended her: "You say Mrs. Piozzi's style, in

conversation, is exactly that of her travels. Our interviews were

only two; no vulgarness of idiom or phrase, no ungrammatic inelegance

struck me then as escaping, amidst the fascination of her wit, and

the gaiety of her spirit; but inaccuracies and ungraceful expressions

often pass unnoticed in the quick commerce of verbal society, that

are very disgusting after their deliberate passage through the pen."

The critics found fault with her matter as well as her manner, as did

Gifford in the often quoted lines:

"See Thrale's grey widow with a satchel roam,

And bring in pomp laborious nothings home."

But she bore him no malice, and took her revenge by obtaining

an invitation to a house where he was dining, to his obvious

embarrassment, from which she relieved him by proposing "a glass of

wine to their future good-fellowship."

As long as the Piozzis and Westons were living close together in town,

there was naturally little occasion for letters, but they recommence

in 1789 when Sophia had gone to Bath after an illness. On 13th April

Mrs. Piozzi writes from Hanover Square, after a visit to Drury Lane:

"I have scarcely slept since for the strong agitation into which

Sothern and Siddons threw me last night in Isabella"; while her

husband adds a P.S.: "I assure you I cried oll (_sic_) the Tragedy."

This was no doubt Sothern's _Fatal Marriage_, in which Mrs. Siddons

took the part of the heroine Isabella, a character in which she was

painted by William Hamilton. Mrs. Piozzi was much interested in the

thanksgiving for the King's recovery after his first illness, "the

most joyful occasion ever known in England"; for which she wrote an

Ode, which was printed (with emendations that greatly annoyed her) in

the _Public Advertiser_. For the State procession to St. Paul's on

23rd April, Miss Weston had secured them places in a balcony, "which,

if it tumbles down with our weight, why we fall in a good cause, but I

wish the day were over."

This summer the Piozzis went northwards, intending, as it would

seem, to emulate Johnson's Highland tour. On 11th July she writes

from Scarborough: "We like our journey so far exceeding well, but

'tis as cold as October, and just that wintry feel upon the air;

a Northern Summer is cold sport to be sure, but Castle Howard is

a fine place, and the sea bathing at this town particularly good.

What difference between Scarbro' and Exmouth! yet is this bay by no

means without its beauties, but they are more of _Features_ than

_Complexion_." They made their way north as far as Edinburgh, but the

projected Highland tour was given up; the biographers say on account

of Cecilia's delicacy, but in a letter in Mr. Broadley's collection,

written from Glasgow, 26th July, she says: "Our weather has been so

very unfavourable here, and my own health so whimsical, I fear Mr.

Piozzi will not venture far into the Highlands." The first letter of

sufficient interest to be quoted at length is written from the Capital.

EDINBURGH, _10 Jul. 1789_.

And so you will not write again--no, _that_ you will not, Dear

Miss Weston,--with all your mock Humility!--till Mrs. Piozzi

answers the last letter, and begs another. Well! so she does

then: I never was good at _pouting_ when a Miss; and after

fifteen years are gone, one should know the value of Life

better than to _pout_ any part of it away. Write me a pretty

Letter then directly, like a good girl, and tell me all the

News. The emptier London is, the more figure a little News

will make, as a short Woman shows best at Ranelagh when there

is not much company. Echoes are best heard too when there are

few People to break the sound, you know, so let the Travelling

Trunks, Hat Boxes, and Imperials that pass over Westminster

Bridge every Day at this time of the Year, be no excuse for

your not writing. We have had a good Journey, and the Weather

cannot be finer; a Northern Latitude is charming in July, and

the long Days here at Edinburgh delightful--but no Days are long

enough to admire its Situation or new Buildings, the symmetrical

beauties of which last quite exceed my expectations, while the

Romantic Magnificence of the first is such as gives no notion

at all of the other. So I like Scotland vastly; and as we have

Engagements for every Day, one should be ungrateful not to

like the Scotch too. But for that my heart was always equally

disposed.... I am much flattered with finding my Book read here,

and everybody talks about _Zeluco_, but I hope no one more than

myself, or with more true esteem of its Author....

The full title of the work just mentioned was _Zeluco, various views

of Human Nature, taken from Life and Manners, Foreign and Domestic_,

its object being "to trace the windings of vice, and delineate the

disgusting features of villany." Its author, John Moore, M.D., an army

physician, tutor to Douglas, eighth Duke of Hamilton, and father of

General Sir John Moore, is frequently mentioned in the letters. He was

in Paris during the massacres of the Revolution, and published the

Journal kept during his residence there in 1793.

The Piozzis returned southward by Glasgow and the Lake District to

Liverpool.

LIVERPOOL, _Sat. 22d Aug._

So dear Miss Weston, and her Hanover Square friends, have shared

all the delights that _Water_ can give this hot weather, while

"A River or a Sea

Was to us a Dish of Tea," &c.

Meantime I do not tell you 'twas judiciously managed to run from

Lago Maggiore to Loch Lomond, and finish with the Cumberland

Meres, any more than it would be wisely done to put Milton into

the hands of a young beginner; and when good taste was obtained,

lay Thomson's charming _Seasons_ on the desk; then make your

Pupil close his studies with Waller's poem on the Summer Islands.

Beg of Major Barry to make my peace with his countrymen; some

one told me the other day they were offended at a passage in

y^e _Journey through Italy_, and I should be very sorry on one

side my head, and much flattered on the other, _that they should

think it worth their while_....

We spent a sweet day at Drumphillin, near Glasgow, in

consequence of Dr. Moore's attentive kindness, and even from

that charming spot continued to see the majestic mountain which

attracted all my admiration, and which still keeps possession

of my heart. I took _my_ last leave of it from the Duke of

Hamilton's Summer House, but at a distance of seventy or eighty

miles it may be discerned. If you ask me what single object has

most impressed my mind in this journey of 800 miles round the

Island, I shall reply BEN LOMOND....

If I promised you an account of Glasgow, I did a foolish thing;

what account can one give of a very fine, old-fashioned,

regularly-built, continental-looking town?--full as Naples, yet

solemn as Ferrara: after Glasgow too, everything looks so little.

I think Mr. Piozzi must write the account of _this_ town, he

is all day upon the Docks, and all night at the Theatre; both

are crowded, yet both are _clean_: the streets embellished

with showy shops all day, and lighted up like Oxford Road all

night; a Harbour full of ships, a chearful, opulent, commodious

city. Have you had enough for a dose? and will you give all our

compliments to all our friends, and will you love my husband and

Cecilia?

The Major Barry above mentioned, apparently a member of an Irish

family, is frequently referred to in the letters. He became a Colonel

in 1790, and acted as A.D.C. to Lord Rawdon (afterwards Marquess of

Hastings) in the American War, in which capacity he sent home "the

best despatches ever written." Retiring from the Army in 1794, he

settled in Bath, where he was a prominent figure in literary and

scientific circles till his death, which occurred shortly after that

of Mrs. Piozzi.

From Liverpool they went to inspect Mrs. Piozzi's Welsh property, and

the next letter gives the first hint of the idea of building a house

on it, which was carried out later on. Perhaps the postscript was

hardly meant seriously, as no steps were taken in the matter for some

years, and Mrs. Piozzi herself states that the suggestion was made by

the Marquis Trotti, who does not appear upon the scene till 1791.

DENBIGH, _Tuesday 1 Sep._

DEAR MISS WESTON,--I thank you for your invitation

to pretty Ludlow, and shall let you know when we are likely

to arrive there, that all possible advantage may be taken of

your friendly hints. Mr. Knight is an old acquaintance of my

Husband by the description you give of his taste and elegant

conversation; at least it would be strange should there be _two_

such men of any _English_ name. Scotch and Welsh families are

disposed in a different manner: _we_ have but so many names, and

all who bear those names are related to each other. I find a

great resemblance between the two nations, in a hundred little

peculiarities, and the Erse sounded so like my own native tongue

that I wished for erudition to prove the original affinity

between them.

The French nation was never a favourite of mine, and I see

little done to encrease one's esteem of them _as_ a nation.

Their low people are very ignorant, their high ones very

self-sufficient: you now read in every Paper the effects of

that self-sufficiency acting upon that ignorance. Fermentation

however will, after much turbulence, at length produce a _clear_

spirit, though probably 'twill be a _coarse_ one. They will know

in a dozen years what they would have, and I fancy _that_ will

be once more an Absolute Monarchy....

Mr. Piozzi adds a _P.S._ "In a few days I intend go to see

our little estate, and choose the place to building a little

Cottage, and a little room for our dear friend Miss Weston....

G. P."

In her remarks on surnames Mrs. Piozzi does not display her usual

acumen. There is hardly any English name of which it can safely be

predicated that all the individuals who bear it are related to each

other, and assuredly this is not the case with a name like Knight.

She shows more penetration in her estimate of the trend of events in

France, where the mutterings of the coming storm were already making

themselves heard. The States-General had assembled in May, in June the

Commons had constituted themselves the National Assembly, the Bastille

had fallen on 14th July, and on 4th August the nobles had relinquished

their hereditary privileges. Well within the twelve years which she

postulates, the Revolution of Brumaire (1799) had practically put the

supreme power in the hands of Bonaparte as First Consul, though he was

not proclaimed Emperor till 1804.

From North Wales they went, by way of Ludlow, to Bath, probably for

the benefit of Piozzi, who was already beginning to suffer from the

attacks of gout which finally proved fatal.

BATH, _2 Nov. 1789_.

DEAR MISS WESTON,--Not _one_ letter do I owe you, nor

_three_ nor _four_, but forty if they would make compensation

for your kind ones to Ludlow, where Miss Powell's politeness

made the time pass very agreeably indeed, spight of rain, which,

however provoking, could not conceal the beauty of its elegant

environs, even from an eye made fastidious by the recent sight

of richer and more splendid scenery.

Mrs. Byron read me the kind words for which Mr. Piozzi and I

owe you so many thanks: she gains strength daily, and will be

quite restored if kept clear from vexation, and indulged in her

favourite exercises of riding and the Cold Bath. My husband and

she have many an amicable spar about _Bell's Oracle_, on account

of his savage treatment of dear Siddons, whose present state of

health demands tenderness, while her general merit must enforce

respect. I wonder, for my own part, what rage possesses the

people who wish to see, or delight in seeing, virtue insulted.

Let us not learn to tear characters in England, as persons

are torne in France, and drink the _intellectual life_ of our

neighbours warm in our Lemonade.

Major Barry has written me a charming letter, Do tell him that

he shall find my acknowledgements at Lichfield; I mean to write

a reference to Miss Seward, about a critical dispute we had here

at Bath some evenings ago, concerning the two new novels, which

I find are set up in opposition to each other, and people take

sides. You will easily imagine that _Zeluco_ and Hayley's _Young

Widow_ are the competitors.

Give my kind love to Miss Williams when you see her, and tell

her that she is one of the persons I please myself with hoping

to see a great deal of this winter.

We are all going to the Milkwoman's Tragedy to-morrow; I fear

with much ill will towards its success. Her ingratitude to Miss

More deserves rough censure, but hissing the play will not mend

her morals.

Miss Wallis is to play Belvidera next Saturday. She is scarcely

more of a woman than Cecilia Thrale, and quite as young looking;

very ladylike though, and a pretty behaved girl in a room. I

advised Dimond in sport to act Douglas to her Lady Randolph,

as a still more suitable part than Belvidera. Here's nonsense

enough for one pacquet. 'Tis time to say how much I am dear Miss

Weston's affect^e servant

H. L. P.

Mrs. Byron, whose name frequently recurs in the letters, was a

daughter of John Trevannion, who married, "pour ses péchés," as Mrs.

Piozzi elsewhere remarks, Admiral the Hon. John Byron, known in the

Service as Foulweather Jack, the grandfather of the poet.

The attack on Mrs. Siddons in _Bell's Oracle_ was one of the rare

exceptions to the general chorus of praise she commonly evoked from

the Press; it seems to have been quite undeserved, and her reputation

was far too firmly established to be shaken by it.

_Zeluco_ has already been referred to. Its competitor, _The Young

Widow, or a History of Cornelia Sudley_, was the work of William

Hayley, the poet, of whom Southey said: "Everything about that man is

good, except his poetry." Yet it hit the popular taste, and he was

even offered the Laureateship in succession to Warton.

The Milkwoman, Anna Maria Yearsley, otherwise "Lactilla," was a rustic

genius discovered by Hannah More, who brought out a volume of her

poems, for which she wrote a preface. But her action in investing the

proceeds for the benefit of the authoress, without giving the latter

any control of the money, produced a rupture between them, and the

quarrel was carried on in the Press "to a disgusting excess," as their

contemporaries thought. Besides her play of _Earl Godwin_, she wrote

a novel called _The Royal Captives_, which met with some success, so

that she was enabled to set up a Circulating Library at the Hot Wells,

Clifton.

Miss Wallis, whose career began in the Smock Alley Theatre, Dublin,

had just made her first appearance in England at Covent Garden, where

she played Belvidera (in Otway's _Venice Preserved_) and other leading

parts, with some success. But she seems to have found provincial

audiences more appreciative, and played regularly at Bath and Bristol

for five years.

In 1814, several years after his death, Mrs. Piozzi writes in her

Commonplace Book: "Dimond the Bath Actor was, of all _common mortals_

I have known, completely the best. So honourable that he left no debts

unpaid, so prudent that he never overran his Income, Pious in his

family, pleasant among his friends. Temperate in his appetites, and

courageous to conquer the passion which no man could have felt more

strongly."

With the return of the Piozzis to Town the letters cease until the

summer of 1790, when the tenant vacated Streatham Park, and Mrs.

Piozzi found herself again established there, but under happier

auspices. In May and June she scribbles hasty notes of invitation

to Miss Weston, explaining that "the Hay is carrying, the Weather

changing, and even the Master of the House going to Town on horseback,

because Jacob must not be disturbed." The special attraction held

out was the presence of Mrs. Siddons, but illness prevented Miss

Weston from coming till it was too late to meet her. Mrs. Siddons was

herself suffering from some trouble, apparently rather mental than

physical, for she adds at the end of one of Mrs. Piozzi's notes: "I

fear my heart will fail _me_ when _I_ fail to receive the comfort and

consolation of our dear Mrs. P. There are many disposed to comfort

one, but no one knows so rationally or effectually how to do it as

that unwearied spirit of kindness."

STREATHAM, _12 Oct. 1790_.

I am watching the Moon's increase with more attentive and more

interested care than ever I recollect to have watched it since

your project of coming hither with the Colonel has depended on

her getting fat. I am glad he is much at Lord Sydney's, and

hope it bodes well for us all, and that he will soon have his

orders to fight these hateful French, whose pretended love of

England and English Liberty--in good time!--ends at last in

real attachment to Spain, and to the ratification of old Family

Compacts. I never expected better for my own part, and long for

you to come and tell me all the harm of them you know. My Master

looks better, and gains strength every day....

The Colonel here referred to was Colonel Barry, who had recently

obtained promotion, and was hoping for active service. His patron was

Thomas Townshend, second Viscount Sydney, who was Paymaster-General

1767, and Secretary for War 1782.

STREATHAM, _10 Nov. 1790_.

Dear Miss Weston is always partial to _me_, but I think she

now extends her kind thoughts, very charitably indeed, to the

whole race of Authors, when a finely written book so convinces

her of his virtue who wrote it. I do believe however that Mr.

Burke has, in the glorious Pamphlet you so justly admire, given

us _his own true and genuine_ sentiments; and 'tis on such

occasions that a writer shines, like the Sun, with his own

native and unborrowed fire. This book will be a most extensively

useful production at such a moment! and from such a man! Tell me

what charming Miss Seward thinks of it....

[Illustration: STREATHAM PARK

_By J. Landseer after S. Prout. From the Collection of A. M. Broadley,

Esq._]

The Pamphlet was, of course, Edmund Burke's _Reflections on the

Revolution in France_, published this year, which ran through many

editions, and was translated into several foreign languages.

Anna Seward, though a constant correspondent of Miss Weston's, was

never very intimate with Mrs. Piozzi, whose literary style, as

previously mentioned, she detested, though she admired her wit. This

year she lost her father, the Canon of Lichfield, who had long been

an invalid, but she continued to live at the Palace, which he had for

many years occupied.

For the first half of 1791 only two letters are preserved, the first

being written just as the Piozzis had decided to set out on a visit to

Bath.

_Tuesday, 11 Jan. 1791._

My dear Miss Weston did not use to be so silent, I hope it is

not illness or ill-humour keeps her from writing. Here have

been more storms, and very rough ones, since you left us; Lady

Deerhurst apprehends the end of the World, but I think her own

dissolution, poor dear, is likeliest to happen, for she is

neither old nor tough like that, but very slight and feeble....

Peggy, Lady Deerhurst, was the daughter of a neighbour of the Piozzis

at Streatham, Sir Abraham Pitches, Kt., and became the second wife

of George William, then Lord Deerhurst, and afterwards seventh Earl

Coventry. In spite of her feeble health she outlived her husband, and

the dissolution which Mrs. Piozzi anticipates did not happen for near

half a century.

Early in February the Piozzis went to Bath, from which place the next

letter is written.

_11 Feb. 1791, Fryday._

My dear Miss Weston must be among the very first to whom I give

an Acct. of our safe arrival at a comfortable House, corner of

Saville Row, Alfred Street. We ... ran hither in one day from

Reading, but I found a strange Giddiness in my Head that was

not allay'd by the noisy concourse of young Gamesters, Rakes,

&c., at York House, where we staid till this Lodging was empty:

and here I have good Air and good Water, and good Company--and

at last--_good Nights_; so that I mean to be among the merriest

immediately. The Place is full, and the pretty girls kind, as my

Master says, so you must write pretty eloquent letters to hold

his heart fast....

Miss Hotham's accounts of our sweet Siddons are better than

common, so when things are at worst they mend, you see. Mr.

Kemble's illness, gain'd only by shining too brightly, and

wasting the Oyl in the Lamp, while here at Bath, is recovered by

now I hope, and his spirits properly recruited....

Cecilia was fourteen years old three days ago, and all the

ffolks say how she is grown, &c....

The letters cease after their return to Streatham, until Miss Weston

in her turn went to stay with friends at Bath. Those which follow are

full of an incipient romance which appealed strongly to Mrs. Piozzi,

inasmuch as it bore a strong resemblance to her own. An acquaintance

of her husband's, a certain Lorenzini, Marquis Trotti, their guest at

Streatham, had been struck by the charms of Harriet Lee (afterwards

joint authoress of the _Canterbury Tales_), who was now helping her

sister Sophia in the school at Belvidere House. But considerations

of worldly prudence, which had so far held him back from an actual

declaration, seem finally to have prevailed, in spite of Mrs. Piozzi's

well-meant encouragement. The final act of the drama is somewhat

obscure, but from hints let fall in subsequent letters Harriet Lee

would appear to have had rather a fortunate escape.

STREATHAM PARK, _Thursday, 28 Jul._

MY DEAR MISS WESTON,--I was happy to find the

Prescription, which, after all, I did not find, but made little

Kitchen copy. Do not forget Streatham, nor remit of your

kindness towards me, or towards those I love, dear Harriet in

particular: I hope you will contrive to see her very often.

Marquis Trotti is sensible of your partiality, and deserves all

your esteem. His behaviour is such that were he my son I should

kiss him, were he my brother I should be proud of him, and as

he is only my good friend, I pity and respect him. There is

much tenderness, joined with due manliness, in his character;

he is a very fine young fellow.... But as Hermione says in the

_Midsummer Night's Dream_:

"I never read in Tale or History

That course of true Love ever did run smooth,

But either it was crossed in _Degree_," &c.[3]

[3] _Midsummer Night's Dream_, I. i, 134.

Well! if 'tis of the right sort, opposition will but encrease

it, and as Marquis Trotti said to Buchetti in my company

yesterday, "The time is approaching when aristocratic notions

about marriage will fall to ground, and then those who have

sacrifized their happiness to such folly will look but like

Fools themselves."

Show this letter to our lovely and much beloved Harriet; she

is, I think, the object of a very honourable and a very tender

passion, and to a mind like hers that ought to be a very great

comfort....

Write to me only in general, not _particular_ terms. Write very

soon tho', or I shall be gone to Mrs. Siddons's.

The great actress was seeking retirement and country air at Nuneham

Courtney, on the banks of the Thames below Oxford, and thither all

the Streatham household shortly betook themselves.

Buchetti, whom Mrs. Piozzi had known for some years, was evidently

a friend of Trotti, but seems, in spite of his Italian name, to

have been a Frenchman. There is a letter from him in Mr. Broadley's

collection, dated Paris, 11th June 1789, written in English, and

signed Abbé de Buchetti, telling Mrs. Piozzi that he had written to

her from Cadiz in October 1788, giving an account of his travels in

Andalusia, &c. He goes on to mention the forthcoming meeting of the

French Estates to debate on the new Constitution, which he expects

will be very interesting, and at which he hopes to be present. He adds

compliments from Trotti.

The following lines by Mrs. Piozzi, dated Streatham, 6th July 1791,

occur on a loose sheet among the letters:

"By Friend Howard instructed our Virtue t' advance,

The difference is found 'twixt Great Britain and France;

Old England her Pris'ners to Palaces brings,

While the Palace in France makes a Prison for Kings."

RECTORY HOUSE, NUNEHAM,

_6 Aug. Saturday_.

I promised my dear Miss Weston a long Letter from sweet

Siddons's fairy Habitation, but had not an Idea of finding

as elegant a Thing as it is. England can boast no happier

Situation; a Hill scattered over with fragrance makes the

Stand for our lovely little Cottage, while Isis rolls at his

foot, and Oxford terminates our view. Ld. Harcourt's rich Wood

covers a rising Ground that conceals the flat Country on the

Left, and leaves no Spot unoccupied by cultivated, and I may

say peculiar Beauty. How I should love to range these Walks

with my own dear Streatham Coterie!--but now it is all broken

up. The Marquis and my Master with M. Buchetti left us this

Morning in search of Sublimer Scenes: I have given them a Tour

into Wales--Cecilia and myself sit and look here for their

Return--_that is for my Husband's_--unless Miss Owen's summons

or Signal of distress lures me to Shrewsbury, where I could wait

for _him_ and be nearer. They will reach Worcester to-night, and

visit Hagley to-morrow I trow. Never did mortal Nymph speed her

_polish'd_ Arrow more _surely_ than has our Harriet done: never

did stricken Deer struggle more ineffectually against the Shaft

which has fix'd itself firm in his Heart than does her noble

Lover. He has however no Mind, I fancy, to give up without an

Effort--but no one better knows than I do the difficulty, up to

impossibility, of such an Operation. _She_ too feels, and feels

sincerely, I'm sure; these are the true lasting Passions; when a

serpentine Walk leads they _know not whither_: for in Love, as

in Taste, I see

"He best succeeds who pleasingly _confounds_;

Surprizes, varies, and _conceals_ the _Bounds_."

Console and sooth her, _do_, my charming Friend, she will find

these five or six Weeks as many Years--but by then she will have

her Admirer at the Hot Wells, where he may drink the Water to

advantage. He is already much altered in countenance, but _so_

interesting!...

There is nothing like living near a Nobleman's house for making

a _Democrate_ of one: here has been such a deal of Ceremony

and Diddle Daddle to get these Letters frank'd as would make a

plain Body mad--and I see not that you or Harriet will get them

either quicker or cheaper for all the Ado we have made at last,

but now I am out of Parliament myself I will beg no more Free

Cost directions. Oh! would you believe the Gypsies have told

Truth to Marquis Trotti? They said he would have a great Influx

of Money soon--_Yellow Boys_ you know they called them: and he

said what stuff that was, because his Fortune could not easily

admit of Increase, as it was already an entail'd Estate--and

all his expectations well known to himself. But a few days ago a

Letter from Italy informed him of unclaimed Dividends found in

the Bank of Genoa, which might be his for asking. _He will not

go over_ to ask for them however; but sent his Father word he

was indifferent about the Matter--he had enough &c.--he is of

Aspasia's mind entirely--

"Love be our Wealth, and our Distinction Virtue."

His Income can be in no Danger though, do what he will: at

least a very considerable one, of which I am glad: he is a

deserving Character indeed, and will, I hope, lose very little

by his Sentiments of Dignity and Sensibility of Heart. Let our

Harriet read all this, I had no room for another Word in that

I sent _her_. How beautiful a bit of writing did she send me

upon leaving Streatham! I wish, when her Hand's _in_, some

clever verses would but drop from it: tell her I say so: this

is Inspiration's favourite Hour. How pleased it would make me

if I were but addressed in them! Her Talents have really made a

glorious Conquest, and she ought to cherish them. I long for the

sight of her dear pale Ink, that I do....

It appears so strange and so shocking to put up my Letter

without speaking of Miss Seward, that I can't bear it; nobody

has such a notion of her Talents as I have, though all the world

has talked so loudly about them. Her Mental and indeed her

Personal Charms, when I last saw them, united the three grand

Characteristics of Female Excellence to very great Perfection: I

mean Majesty, Vivacity, and Sweetness.

Well! you may speak as ill of Bath as you please, but I wish

I was there, and never look at old White Horse Hill, which

one sees from the Terrace, without sighing to pass it on the

Road--but Fate calls to Shrewsbury--and thither I shall hie me

on the 20 of this Month. And now remember Missey, that to kindle

and keep up a Man's Love so as to make him ardent enough

for the _overleaping_ Objections, is the true duty of prudent

Friendship; not to make him _talk_ of those _very Objections_

which we know already, and which will only strengthen by talking

of. So God bless you all, and love your

H. L. P.

The Aspasia here quoted appears to be the heroine of Beaumont and

Fletcher's _Maid's Tragedy_.

[Illustration: ANNA SEWARD

_By W. Ridley after Romney, 1797. From a print in the British

Museum_]

Harriet Lee, as desired by Mrs. Piozzi, wrote the verses on Streatham

Park which are given below.

VERSES TO MRS. PIOZZI,

_10 Aug. 1791._

(BY HARRIET LEE)

From the bright West the orb of Day

Far hence his dazzling fires removes;

While Twilight brings, in sober grey,

The pensive hour that Sorrow loves.

Tho' the dim Landscape mock my Eye,

Mine Eye its fading charm pursues:

Ah! tell me, busy Fancy, why

Thro' the lone Eve thou still would'st muse?

More rich perfume does Flora yield?

Blows the light breeze a softer Gale?

Do fresher dews revive the Field?

Does sweeter music fill the Vale?

No, idle Wand'rer, no!--in vain

For thee they blend their sweetest Powers;

Thine ear persues a _distant_ Strain,

Thy gaze still courts far distant Bowers.

To that loved Roof where Friendship's fires

With pure and generous ardor burn,

Lost to whate'er this Scene inspires,

Thy fond affections still return.

E'en now I tread the velvet plain

That spreads its graceful curve around;

Where Pleasure bade her fairy train

With magic influence bless the ground.

Now, on that more than Syren song,

Where Nature lends her grace to Art,