Project Gutenberg's The Status of the Jews in Egypt, by W. M. Flinders Petrie

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Status of the Jews in Egypt

The Fifth Arthur Davis Memorial Lecture

Author: W. M. Flinders Petrie

Contributor: Philip Sassoon

Release Date: January 27, 2018 [EBook #56444]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE STATUS OF THE JEWS IN EGYPT ***

Produced by MFR and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

WORKS OF ISRAEL ZANGWILL

ESSAYS:

CHOSEN PEOPLES

THE PRINCIPLE OF NATIONALITIES

ITALIAN FANTASIES

WITHOUT PREJUDICE

THE WAR FOR THE WORLD

THE VOICE OF JERUSALEM

NOVELS:

CHILDREN OF THE GHETTO

DREAMERS OF THE GHETTO

GHETTO TRAGEDIES

GHETTO COMEDIES

THE CELIBATES’ CLUB

THE GREY WIG: STORIES AND NOVELETTES

THE KING OF SCHNORRERS

THE MANTLE OF ELIJAH

THE MASTER

THE PREMIER AND THE PAINTER (WITH LOUIS COWEN)

JINNY THE CARRIER

PLAYS:

THE MELTING POT: A DRAMA IN FOUR ACTS

THE NEXT RELIGION: A PLAY IN THREE ACTS

PLASTER SAINTS: A HIGH COMEDY IN THREE MOVEMENTS

THE WAR GOD: A TRAGEDY IN FIVE ACTS

THE COCKPIT: ROMANTIC DRAMA IN THREE ACTS

THE FORCING HOUSE: TRAGI-COMEDY IN FOUR ACTS

POEMS:

BLIND CHILDREN

_UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME_

Cloth 2/- net. Paper 1/- net.

The Arthur Davis Memorial Lectures:

CHOSEN PEOPLES

By ISRAEL ZANGWILL

_Second Impression_

With a Foreword by the Rt. Hon. Sir HERBERT SAMUEL, M.A., High

Commissioner of Palestine

WHAT THE WORLD OWES TO THE PHARISEES

By the REV. R. TRAVERS HERFORD, B.A.

With a Foreword by General Sir JOHN MONASH, G.C.M.G., K.C.B., D.C.L.

POETRY AND RELIGION

By ISRAEL ABRAHAMS, M.A., D.D.

Reader in Rabbinic at the University of Cambridge

With a Foreword by Sir ARTHUR QUILLER-COUCH, M.A., D.Litt.

SPINOZA AND TIME

By S. ALEXANDER, M.A., LL.D., F.B.A.

Hon. Fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford; Professor of Philosophy in the

University of Manchester

With an Afterword by VISCOUNT HALDANE, O.M., F.R.S.

THE STATUS OF THE JEWS IN EGYPT

Being the Fifth “Arthur Davis Memorial Lecture” delivered before

the Jewish Historical Society at University College on Sunday,

April 30, 1922

--------------

Iyar 2, 5682

[Illustration]

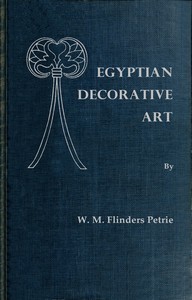

[Illustration: FRAGMENT OF AN ANCIENT HEBREW PAPYRUS—THE OLDEST IN THE

WORLD—DISCOVERED BY PROFESSOR FLINDERS PETRIE.

For translation see Appendix.]

THE STATUS OF

THE JEWS IN EGYPT

BY

W. M. FLINDERS PETRIE

D.C.L., LL.D., F.R.S., F.B.A.

_Edwards Professor of Egyptology, University College_

WITH A FOREWORD BY

Sir PHILIP SASSOON, Bart., M.P.

LONDON: GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN LTD.

RUSKIN HOUSE, 40 MUSEUM STREET, W.C.1

_All rights reserved_

_First published in 1922_

NOTE

The Arthur Davis Memorial Lecture was founded in 1917, under the auspices

of the Jewish Historical Society of England, by his collaborators in

the translation of “The Service of the Synagogue,” with the object of

fostering Hebraic thought and learning in honour of an unworldly scholar.

The Lecture is to be given annually in the anniversary week of his death,

and the lectureship is to be open to men or women of any race or creed,

who are to have absolute liberty in the treatment of their subject.

FOREWORD

By Sir PHILIP SASSOON, Bart., M.P.

I thank the Society for the honour they have done me in asking me to

preside upon so interesting an occasion. Professor Petrie needs no

introduction; and I can but express the gratitude of the meeting to

him for coming to lecture on an absorbing topic. We should have to go

very far to find a more eminent Egyptologist. He is not limited to

a discussion and criticism of other men’s discoveries; he is a most

successful excavator himself. He has with his own hands unearthed many

objects of the deepest interest to all students of the remote Egyptian

past. He has been engaged in this work for forty years, during thirty

of which he has occupied the distinguished position of Professor of

Egyptology at this University, where he has spoken with peculiar

authority on the significance of his own and other men’s discoveries,

and has interpreted them to laymen such as myself. The late Arthur

Davis, in whose memory these lectures are held, was a type of that rare

and valuable man who, while engaged in business, is yet inspired by a

studious ambition. He was a man above the average, who taught the lesson

to the average man of affairs that the delights of learning are open to

all those who are able to make use of the opportunities they can find and

create. Such men are an honour to any cultured community.

The Status of the Jews in Egypt

In considering the history of any people, one of the main elements is

that of their status. What were their abilities and how were they shown?

What permanent mark did they make on their period? How did they stand

in reference to their neighbours, in the same country and in other

countries? There are now Jews in Lemberg and Jews in Paris; but how

entirely differently we regard them, because of their status. How utterly

diverse is the mark left on the world by the men of mind, by Isaiah or

Aristotle, compared with the energies of patriots, like the Maccabees

or Sulla. Mere existence matters nothing to the present or the future;

it is the energizing influence of fresh thoughts or organization that

alone gives value to any people. Various races at present who think a

great deal of themselves have never added a single idea or capability

to the rest of the world, their status is simply that of incapable

dependence upon the civilization of others. Regarding then the dominant

importance of status, it seemed that it would be useful to focus together

the various fragments of views that have been gained as to the position

occupied by the Jewish race in Egypt at different periods.

We may glance first at the earlier relations of Semites with Egypt. The

second prehistoric civilization was of Eastern origin; and judging by the

strong analogies of the Egyptian language with Semitic speech, it seems

probable that this prehistoric age was dominated by a race which later

developed into the historic Semites.

Coming into recorded history, we can now realize, from recent

discoveries, how the VIIth and VIIIth Egyptian dynasties which overthrew

the earlier pyramid builders were Syrian kings ruling over Egypt. Their

personal names are preserved in some reigns on the great list of kings

at Abydos,[1] and their status is recorded by a cylinder of one of

these kings[2]—Khondy—bearing a figure of a flounced Syrian before him,

and an Egyptian in the background. The king himself has his name in a

cartouche and wears the crown of Upper Egypt; so he did not rule only

over the Delta, and his name being at Abydos points to control of the

whole country. As to the language, the names of these kings appear to

be Semitic, as Telulu the exalted, Shema the high, Neby the prophet.

All of this accords closely with the recent publications of Professor

Albert Clay[3] on the importance of a north Syrian kingdom, as the real

centre of the Semitic peoples, rather than Arabia, which he regards as a

backwater, where an early type has remained undisturbed. His appeal to

the Semitic names in early Babylonia shows that they are quite as early

as—or earlier than—the Sumerian.

This Semitic conquest of Egypt had a close parallel in the Hyksos

invasion of Egypt. The Hyksos or “princes of the desert,” as they call

themselves, were nomadic Semites who pushed down into Egypt during the

weak condition of the country in the XIVth dynasty. Even during the

XIIth dynasty there had been small bodies of Semites coming in, as shown

by the celebrated scene at Beni Hasan, where Absha heads a party of 37

Amu;[4] or on a scarab of User-Khepesh, who was the guardian of 110

Amu.[5] At last a flood of nomads, probably driven south by a famine

period of drought, burst into the country, much like the Arab invasion

of the age of Islam. After plundering the country they settled down,

as earlier invaders had done, by adopting the system which they had

found there, and becoming kings of Egypt, who restored and enlarged the

temples and encouraged learning.[6] They continued, however, attached to

their earlier life; and the remains of one king—Khyan—being found as far

apart as Crete and Baghdad, indicates that they kept up a wide trade,

if not an extensive rule.[7] The title adopted by that king, “embracing

territories,” shows that he probably ruled Syria as well as Egypt, like

the Syrian King Khondy in the VIIIth dynasty.

It is the nature of the Hyksos rule that enables us to realize the actual

setting of the first stage of Jewish history. It is as one of the late

waves of nomadic Hyksos that the account of Abraham must be viewed.

Wandering round the Syrian desert, as the Hyksos had done, drifting

up and down the ridge of hill pastures of Palestine, passing in and

out of Egypt as necessity led, the life in the Patriarchal narratives

gives the picture of the life of the “shepherd kings,” the “princes of

the desert.” The status of these Hebrew wanderers was just that of the

people among whom they came in Egypt, the ruling caste of the country,

who sat upon the more industrious but less independent Egyptians. They

would naturally be received with the affability, and on the easy terms,

which are represented. That this was taken in the course of the Hyksos

rule is shown by the king having adapted himself to Egyptian feeling, and

its being unsuitable to let pure nomads come in to the cultivated Delta,

because the shepherds were an abomination to the Egyptians. Hence, though

on perfectly good terms, it was preferred to keep these fresh nomads on

the border, in the Wady Tumilat, rather than revive the antagonism of the

agriculturalist. The story of Joseph falls into place most naturally in

Egypt, where even under purely Egyptian kings the highest positions could

be held by Pa-khar or Nehesi, “the Syrian” or “the negro.” That this was

during a Semitic rule is suggested by the tide of Joseph being _Abrekh_,

the _Abarakku_ minister of state of Babylonia.[8]

The great change of status took place when the Hyksos were expelled,

and any remnant of those tribes had to become serfs if they were

tolerated at all. It seems highly probable that at this time a part

of the Israelites were swept back into Palestine with the retreating

waves of defeated Hyksos. It is not only probable, but it is indicated

by the defeat of “people of Israel” in Palestine by Merneptah (recorded

on his triumphal stele)[9], at a time when the Israelites whom we know

of seem to have still been in Egypt. Of the latter portion—with whom

we are here concerned—we have only accounts of their serfdom; yet a

stray light of a different kind has lately shown that other positions

were open to them. On a large family tablet of a chief of cavalry under

Rameses II, that is during the age of oppression, the Egyptians are shown

worshipping the various gods of the country. The surprise comes where the

servants have put their names on the blank edges of the tablet, headed

by the “scribe engraver” called Yehu-naam or “Yehu-speaks”;[10] just

the converse order of the most familiar phrase, “Thus saith the Lord.”

This seems unmistakably to refer to a worshipper of Yehu or Yahveh, and

hence an Israelite. Though this is only a single name, it implies a great

deal. It shows that an Israelite during the oppression was not only an

unskilled labourer, but might be one of the most highly skilled artisans,

understanding hieroglyphics, and an artist able to draw and engrave all

the figures of the gods. This puts an especial point on the commandment

against making graven images, if Israelites were actually engaged in

that trade. Further, this man was employed as far south as the Fayum,

and thus a hundred miles from the tolerated “Jewry” of the Wady Tumilat.

The freedom which the Israelites undoubtedly had under the Hyksos makes

it likely that many may have taken up different crafts, and have been

scattered about in the country as demand and opportunity led them.

Those who remained in a servile position were not in the least in the

condition of being separately bought and sold like cattle, as in American

slavery. They were organized in regular families, with their scribes

or “officers” of themselves, under the “commanders of tribute” of the

Egyptians.[11] In short, their labour was a sort of tribal tax which they

had to render, and for which their own headmen were responsible. How and

when the individual worked was the affair of his own family and clan, and

could not be dictated by the Egyptian so long as the total output was

maintained. This is an important part of the status of labour, whether

its system is autonomous or is an individual slavery. It seems that the

status was that of a tribe heavily taxed for labour, but left to follow

its own arrangements. This could only be carried out where there was a

solid block of the Israelite population, as in the land of Goshen, the

Wady Tumilat. It does not therefore imply any special tax or disability

upon those who—like the sculptor just named—had entered on various trades

and work scattered in the country. Probably they were gradually lost to

sight in mixture with the general population.

During the age of the Judges there was a continuous decadence in Egypt,

so that on both sides it is improbable that trade led to any Jewish

settlements. The rise of the Jewish kingdom, and the regular horse

trade established by Solomon, together with his marriage to the royal

family of Tanis, Zoan, and consequent connection with the royal family

Bubastis,[12] must have led to some mercantile establishments. Still

greater familiarity with Egypt came during the increasing troubles of

the close of the Jewish kingdom. About seventy years before the fall of

Jerusalem the new Saite King, Psamtek, had established a great frontier

fort on the road to Palestine, at Tahpanhes; this was a settlement of

Greek troops, and hence open to foreign residents.[13] Whenever there

was trouble in Judæa, especially from Assyria, this fortress would be the

natural asylum of any refugees, and Greek and Jew first mixed here and

learned each other’s ways. The results of this mixture are evident in the

reference to five cities speaking the language of Canaan, and swearing by

the Lord of Hosts, and in the address of Jeremiah to the Jews which dwelt

in the land of Egypt, which dwell at Migdol, the desert frontier, and at

Tahpanhes, the Delta frontier, and at Noph, Memphis, and in the country

of Pathros, Upper Egypt,[14] calling their attention to the desolation

of Jerusalem and exhorting them therefore to give up burning incense to

other gods in the land of Egypt, where they had gone to dwell already,

more than ten years before the fall of Jerusalem. Their reply that they

had prospered when they sacrificed to the queen of heaven was met by the

prophecy that Pharaoh-Hophra should be given into the hand of his enemies

and into the hand of them that seek his life.[15] The meaning of this lay

in the politics of Egypt. Hophra was of the party that favoured Greeks

and foreigners; but there was a strong Nationalist party of Egyptians

who would exclude foreigners, and they sought the life of Hophra, and

finally dethroned and murdered him. This led to the exclusive policy

which restricted foreign residence under Amasis. This declaration was

therefore a warning against trusting to the continuance of the open

policy, under which Egypt had been a refuge to the Jews. The fugitive

remnant of the royal family and court had found what seemed a safe refuge

at Tahpanhes, where the palace-fort had been assigned to them in the

Greek camp by Hophra. There Jeremiah had buried stones in the outside

platform before the entry of Pharaoh’s house, and the fort is still

called “The palace of the Jew’s daughter.” Their patron, however, was to

fall, and the open policy with him, and Amasis was—twenty years later—to

revive the Nationalist control. He closed down all the Greek settlements

and garrisons, only leaving one treaty-port to Greek trade—that of

Naukratis;[16] and they paid for this Nationalist movement by falling

into the power of Persia in the next generation.

The Persian conquest in 525 B.C. threw open the whole country to

influences from all quarters. The series of heads of foreigners found at

Memphis shows how the Babylonian traders of the old Sumerian race flocked

in, with Indians, Kurds, and a multitude of Scythian Cossacks, besides

the ruling race of Persia itself.[17] The picture of this age of Jewish

settlement has been preserved in the papyri of Elephantine;[18] and what

took place there was assuredly exceeded by the less remote settlements

in the rest of Egypt. We find mention of a Jew living at Abydos, which

was not a centre of trade. Not only was there a Jewish colony at the

Cataract, but one large and prosperous enough to build a temple to Yaho.

This temple was older than the Persian invasion, and such a footing is

unlikely to have been a new concession by the Nationalists; it probably

dates from the time of Hophra’s foreign policy before 570.

The description of the parts which were destroyed later shows that there

were five stone doorways, implying that the walls were of brick, like

most buildings in Egypt. There were stone columns, bronze fittings to

the doors, and a roof of cedar. The vessels of the temple service were

of gold and silver. The restorations that have been proposed are rather

too extensive for a temple placed in an existing town. Probably, there

was a continuous high wall around, a large entrance gate opening on an

outer court, from that another gate leading to an inner court, at the

back of which was the colonnade of the temple front; the other three

doorways named would be that of the temple and those leading to the

store-rooms and priests’ dwellings. Though neither the place nor the size

of community would allow of a great building, it is seen that the quality

of the structure implies that the Jewish residents were on a level with

the Egyptians.

Though this temple was destroyed in 411 B.C. by the enmity of the

Egyptian priests of Khnum, and the cupidity of the Persian governor

Widarnag, yet the parties were so nearly equal that before 408 the

governor and all his accomplices had perished by violence, and, in

revenge, by 405 Yedeniyeh bar Gamariyeh, a principal Jew of Elephantine,

had to flee to Thebes, where he was killed.

Regarding the relations of Egyptians to Jews, it is notable that

proselytes were not uncommon. Ashor, an Egyptian, married a Jewess, and

took the name of Nathan; Hoshea was a son of an Egyptian, Pedu-khnum;

Hadadnuri the Babylonian had a son named Yathom, and grandson Melkiel.

Some matters of status which have been attributed to Babylonian

influence may equally well—and more probably—be simple acceptance of

the Egyptian laws. In the census for payment of the temple tax of two

shekels—presumably from householders—at least one in eight are women,

apparently holding independent property. Since in Egypt inherited

property was held by women rather than by men, this was according to

native law. In marriage contracts either party could stand up in the

congregation and denounce the marriage at any time, on payment of a fixed

penalty. This was likewise the case in Christian Coptic marriages, as

stated by a contract.[19] Hence it must be regarded as the Egyptian law,

to which the Jews conformed by necessity or habit.

Thus it appears that the status of the Jewish colonies in Egypt was

at least equal to that of any other foreigners, and that they had

assimilated native custom and law. The ideas of these settlers at

the Cataract, and probably of those elsewhere, were derived from the

habits of thought of the monarchy, quite apart from the Babylonian

particularism. There was no objection to taking an oath by the goddess of

the Cataract, for a legal declaration, like any Egyptian. This is akin

to the later Egyptian Judaism, which sought reconciliation with Gentile

principles, as in the Alexandrian school of Philo, and was entirely

opposed to the bitterly anti-Gentile school which was developed in the

Captivity.

It is evident that there was no hesitation in establishing temple worship

at the Cataract, and probably also in the other cities that “called

on the name of Yahveh,” as a substitute for the destroyed temple of

Jerusalem. This is in accord with the establishing of the temple by

Oniah some three centuries later. There was not yet the dogma that no

temple could be legitimate outside of Jerusalem: that view seems to

have been a development of the Babylonian party, probably in connection

with their rebuilding of the temple at Jerusalem on the Return from

Captivity. A rival temple would probably have been illegitimate at any

time; but if the temple of Jerusalem was destroyed, or in the heretical

hands of the Hellenic party, then it was looked on as more important

to maintain the worship, rather than to abandon it because its true

centre was unattainable. This was in accord with Western Judaism, which

would subordinate the letter of the law to keeping the spirit of it; in

contrast to Babylonian Judaism, which by concentrating on the letter of

the law forgot the more important value of it, and thus “tithed mint,

anise and cummin, and omitted the weightier matters of the law.”

That the settlement at the Cataract was not very exceptional is shown not

only by the reference to a Jewish resident of Abydos[20]—purely a centre

of Egyptian religion—but also by a discovery this year of a rock tomb

of early date which had been re-used about the fifth century B.C.[21]

and inscribed with long documents in Aramaic, equal to over fifty feet

of writing. M. Giron came to examine them, but they are so far damaged

that it would need a longer study than he could spare to transcribe them.

It is to be hoped that some other Aramaic scholar will undertake the

work. This tomb is a few miles back in the eastern desert, opposite to

Oxyrhynkhos. It proves that in this region of Middle Egypt there was also

a Jewish settlement commonly using Aramaic.

The close of the Persian age brought in new conditions under Alexander.

Wide as had been the liberty of Judaism under the international empire

of Persia, it obtained still more liberal treatment from the Macedonian

conqueror. In consequence of the assistance that the Jews had given

against the Egyptians, Alexander granted to them equal rights with

the Greeks in the new foundation of Alexandria.[22] They had there a

separate quarter called the Delta,[23] and they were allowed to be

called Macedonians,[24] to mark them as being under royal protection.

This status in Alexandria, though suspended by Caligula, was renewed by

Claudius. The Jews had also other places assigned to them in Egypt, and

were ruled by an ethnarch, who was chief judge and registrar of the whole

of the settlers.[25]

In the Fayum they naturally found space, as the province was land

reclaimed from the lake, in order to settle Greek troops as colonists. A

village of Samareia is named,[26] also Jews in Psenuris.[27] At Thebes

Simon son of Eleazar was tax collector.[28] Ptolemy Philopator tried to

curb the power of the Jews in Egypt; and the libellous retort on him is

the subject of the third book of Maccabees.[29]

The number of Jews in Egypt, and their familiarity with Greek, led

to various Greek translations of books of the Hebrew Scriptures.[30]

These, in popular rather than literary style, were probably used by

proselytes, and followed in synagogues where Hebrew was drifting out of

use. They were at last compiled, and probably completed by adding all

the remaining books which were familiar as religious literature, though

not canonical. Thus seems to have grown up the Greek version known as

the Septuagint. Its differences from the Hebrew must not all be assigned

to caprice, for its sources probably antedate the formal text of the

Masorah. It represents to some extent the sources of the final orthodox

text. The production of such a body of translation in Egypt is proof of

the large demand that must have existed in a population far more familiar

with Greek than with Hebrew.

The next chapter of the Jewish history in Egypt opens out a wide view.

The troubles in Palestine caused by the Hellenistic party seizing on

the Temple, and the persecutions by Antiochus, had driven large numbers

of Jews to settle in the Delta of Egypt; in fact, as later references

seem to show, the Eastern Delta was largely occupied by Jews. It was the

Hyksos occupation repeated, only in this case the settlement was probably

not that of pastoral nomads, but of agriculturalists and traders. The

extent of the settlement is indicated by the need for a national centre

of worship on a large scale. At first Jerusalem would of course be

entirely the focus of religion; but when the Temple fell into the hands

of the Hellenizing party, and the High-Priesthood became entirely the

prey of violence and bribery, it was more and more difficult to regard

the Holy City as a religious home. This severance, and the distance

across a long desert journey, would lead to an entire estrangement, and

the practical cessation of all Temple worship. The loss of a religious

centre, and the presence of an heir of the High-Priesthood, driven out

of Jerusalem by the crimes of his relatives, would at last lead to the

rise of a new national centre in the midst of the faithful who were

thus living in exile.[31] There must have been a large support for the

project before Oniah would venture to start so great an enterprise. The

vast amount of work that was done in constructing the new city shows

that there was a large and wealthy population involved. The letter of

application for the site, and the reply granted by Ptolemy VII, seem

quite in accord with the times, and there is no reason to suppose

that this title-deed of occupation would be lost to sight, and then

re-invented.

The site having been granted, of a deserted city, with ruins of an

Egyptian palace of Rameses III, and a massive fortification wall of the

Hyksos period, there was abundant material for constructing the new city.

A large area was laid out beyond the wall of the old city, deliberately

modelled upon the plan of Jerusalem and the temple hill. So close is the

copy that Professor Dickie in his study of Jerusalem could combine the

plans to help in restoring the detail of Jerusalem. The old Egyptian site

was adopted as equivalent to the town of Jerusalem, and the new hill

was constructed to copy the Temple, and continued northward to imitate

Bezetha, leaving a deep gap representing the Tyropœan valley. To throw up

these great artificial hills, to face the temple hill with stone walling,

up to 100 feet high, to lay out the new city and the fortifications

covering six acres, must have needed a large body of supporters, and is

the strongest evidence of the numbers and status of the Jews in this

district, about twenty-eight miles north of Memphis.

The status of the Jewish settlers in Egypt was influential. Oniah, the

heir of the High-Priesthood, was associated with Dositheos, another Jew,

as generals of the whole army of Ptolemy VII.[32] He later supported

the widowed queen against the attacks of Ptolemy Physcon.[32] He lived

at Alexandria, and seems to have been powerful in the court. We also

read of an adventurous Jew named Yosef,[33] who outbid all the tax

farmers and obtained great power, which was extortionately used in the

Ptolemaic province of Palestine. Under Ptolemy VII also we find the Jews

of Athribis,[34] the central city of the Delta, dedicating a synagogue.

The spread of Jewish settlement was far beyond the city of Oniah, as

in Caesar’s time the march of troops from Pelusium to Alexandria was

dependent on the goodwill of the Jews of Onion.[35] The road between

those cities is more than fifty miles north of the city of Oniah, and

it seems therefore that the settlement which was in allegiance to that

city must have extended over most of the eastern side of the Delta. As

the Jews were already sharing Alexandria on equal terms with the Greeks,

they must have pretty well absorbed the management of the Delta. It is

in this connection that we must view the statement that they had “entire

custody of the Nile on all occasions.”[36] Probably as holding mortgages

on interest in much of the land of the Delta, they organized a management

of the inundation to ensure the solvency of their securities. The modern

Debt Control taking over the management of the Irrigation Department is

the parallel to the Jewish custody of the Nile.

There was also another and entirely different side of Jewish life in

Egypt. In Josephus we read a long account of the Essenes,[37] to which

sect this Pharisee of the High-Priestly family had devoted himself in

his youth. This account of the Ascetics of Palestine so closely accords

with the account that the Alexandrian Jew Philo gives of the Therapeutae

in Egypt[38] that they seem to be identical. This spread of asceticism

appears to have been started by the Buddhist mission from India. It was

entirely foreign to the Western ideals, yet it took root quickly after

Asoka’s mission. Indian figures are found of this period at Memphis, and

a multitude of modelled heads of foreigners also found there,[17] can

only be paralleled by the modelled heads of foreigners made now for a

Buddhist festival in Tibet, and thrown away as soon as the ceremony is

over. The influence which thus came into Egypt with the Indians of the

Persian occupation is found in working order by 340 B.C., and it was

probably strengthened and organized by the Buddhist mission in 260 B.C.,

and so grew until we meet with the full description of long-established

communities in the pages of Philo and Josephus. These bodies were

apparently composed of philosophical Jews and proselytes largely

influenced by the Alexandrine mixture of Oriental beliefs with Greek

theorizing.

Though we are reviewing the status of the Jews, that must include their

intellectual as well as social position. The Alexandrian school of

thought, as we have it in the Hermetic books[39] and in Philo, was a new

development in the world, freely reasoning on the nature of God and of

man, starting from various beliefs which were chosen for their prominence

and compatibility, and coming to conclusions which are curiously similar

to some modern thought. These ideas are the ground for various dogmas

which naturally grew up from it in the development of that Jewish sect of

Christianity.

We turn from these recluses back to the busy world of the Roman age,

when troops for Caesar at Alexandria were collected by his General

Mithradates, but stuck at Askelon, hindered by the desert and the

Delta.[40] Antipater, a Jewish general with 3,000 Jewish troops, joined

him, organized the desert transport with the Arabs, and then forced the

fortress of Pelusium. On entering Egypt Antipater brought over the Jews

of the Delta to the Caesarian cause, and so opened the way across to

Alexandria, and this induced the Memphite Jews also to join Caesar. This

service was handsomely acknowledged by Caesar.

Augustus rewarded the fidelity of the Alexandrian Jews by giving them a

renewal of all the rights and privileges of equality with the Greeks,[41]

which they had in the original charter of Alexander. They had an ethnarch

and a council, or a president and parliament, of their own; but the

Alexandrian Greeks by their opposition to Augustus lost their right to a

senate.

Trouble began with the insane Caligula,[42] who tried to force the

worship of his own statues in every place. The Jewish refusal of this

demand cost them the withdrawal of all rights of citizenship.[43] The

Greeks then thought it an opportunity for a pogrom to revenge their

subordination under Augustus.[43] On the accession of Claudius the Jews

started a riot to avenge themselves on the Greeks.[44] The influence of

Agrippa, which had checked the persecution of the Jews before, shielded

them again at Rome. Claudius therefore sent a decree,[45] reciting the

equality of the Jews and Greeks in Alexandria from its foundation, and

the renewal of the rights by Augustus. Another more general decree was

published in the Empire, honouring the fidelity of the Jews to the

Romans, and declaring that they were in all countries to keep their

ancient customs without hindrance: “And I do charge them also to use this

my kindness to them with moderation, and not to show a contempt of the

superstitious observances of other nations, but to keep their own laws

only.” By the end of his reign, however, Claudius ejected all Jews from

Rome.[46] Under Nero there was an attempt of Egyptian Jews to liberate

Jerusalem.[47] That failing, there was a renewed riot in the theatre at

Alexandria between Jews and Greeks, ending in calling in the legions to

plunder the Jewish quarter; in hard fight and massacre after it 50,000

are said to have been killed.[48] This seems to have broken the Jewish

hold on the capital, and we do not hear of any more turmoil with the Jews

in Alexandria.

The great war in Palestine and destruction of Jerusalem immediately after

Nero’s reign put an end to Jewish aspirations for a long time. At last a

general conspiracy broke out when Trajan was engaged in Parthia, and the

Jews in Cyrene, Egypt, Cyprus, Palestine and Mesopotamia broke out in

revolt and massacre.[49] Nearly half a million Greeks were slaughtered

in Cyrene and Cyprus.[50] In Egypt all Greeks about the country were

massacred, or driven into Alexandria for refuge, where they massacred

all Jews left in that city. All of this history shows that in numbers

and power the Jews were almost the equals of the Greek population, their

close organization perhaps making up for lesser numbers. The retaliation

by the Roman legions was naturally a full reply to the destruction which

had been dealt out to the Greeks. Henceforward there was no united action

of the Jews.

The great settlement of Onion, occupying most of the eastern Delta, was

depleted at the destruction of Jerusalem by Titus. The Temple of the

new Jerusalem was closed in 71 A.C. by Lupus the Prefect;[51] finally,

Paulinus within the next few years stripped the place, drove out the

priests, shut the gates, and left the place to decay. This repression

was not sheer persecution on the part of the Romans, but was caused by

the Zealots, who had made the worst of the Palestine war, escaping to

Egypt, and going even as far as Thebes.[52] In the interest of peace it

was needful to abolish a religious centre which might have been made a

rallying point for later trouble.

Although history scarcely mentions the Jews in Egypt for some centuries,

they were by no means expelled. As traders, perhaps as cultivators, they

kept a place in the country. A surprise has come in the last few weeks

by the discovery at Oxyrhynkhos, in Middle Egypt, of fragments of four

papyri written in Hebrew, as early as the third century. These are thus

the oldest Hebrew writings known, apart from stone inscriptions. The age

of them is given by another papyrus found with them dated under Severus,

193-211 A.C. One Hebrew writing is on part of a Greek document, which by

the hand is probably of the third century. The style of the Hebrew will

quite agree to this, as it is closely like the synagogue inscriptions

of the first century, as pointed out by Professor Hirschfeld, who has

examined these papyri and made a preliminary transcript. With these

letters are scraps of a liturgical work on parchment with minute writing.

Two of the papyri appear to be dirges, one on the destruction of the

Temple. Another papyrus has Jewish names, Joel, Nehemiah, and others.

Though the Jewish half of Alexandria had been severely, if not

altogether, reduced in the great rebellion under Trajan, there had been

a large return of those who were attracted by the powerful centre of

commerce and activity. Once more a pogrom broke out, from the fanatical

Cyril in 415, who expelled the Jews, while the mob sacked the Jewish

quarter.[53] Yet they returned, as, a couple of centuries later, at the

conquest by Islam the Jews were expressly allowed to remain, according to

the articles of capitulation.[54] During the rule of Islam the position

of the Jew has fluctuated like that of the Christian. Restrictive laws

have sometimes been passed, as that of El Hakim, ordering Jews to

wear bells or to carry a wooden calf,[55] or the later restriction to

wearing yellow turbans.[56] Yet Jews have risen to high power, as the

slave-dealer who became supreme in the childhood of Ma’add about 1040,

and set Sadaka, a renegade Jew, as vizier in 1044.[57] Though in recent

times the Oriental Jew has little hold in Egypt, the European Jew has

been a moving force in finance and enterprise.

The general conclusion appears that Egypt from its position and its

fertility has always attracted the Jew. It has had therefore a notable

influence on the mental attitude, especially in the Alexandrian school of

the Wisdom literature and Philo. The status of the Jewish population has

been fully equal to that of the other important races, native and Greek,

especially in the great Jewish occupation under the Ptolemies, which was

perhaps the age of the greatest political power in Jewish history.

REFERENCES IN TEXT

[1] Petrie, _History_, i, Fig. 6.

[2] Petrie, _Scarabs_, xix; _Egypt and Israel_, Fig. 1.

[3] Clay, _Empire of the Amorites_.

[4] Petrie, _Egypt and Israel_, Figs. 2, 5.

[5] Petrie, _Scarabs_, xv, A.C.

[6] Petrie, _History_, i, Apepa 1.

[7] _History_, i, Khyan.

[8] Hastings, _Dict. Bib._, _Abrekh_.

[9] Petrie, _Six Temples_, 28.

[10] To appear in _Herakleopolis_.

[11] Ex. v. 14.

[12] _Egypt and Israel_, 68.

[13] Petrie, _Tanis_, 11; _Defenneh_, 48-53.

[14] Jer. xliv. 1.

[15] Jer. xliv. 30.

[16] Petrie, _Naukratis_, 7.

[17] Petrie, _Memphis_, 1, xxxvi-xl.

[18] Hoonacker, _Une Communauté Judéo-Araméenne_.

[19] Petrie, _Gizeh and Rifeh_, 42.

[20] Hoonacker, 39.

[21] To appear in _Oxyrhynkhos_.

[22] Josephus, _Wars_, II, xviii, 7.

[23] _Wars_, II, xviii, 8.

[24] _Wars_, II, xviii, 7.

[25] Josephus, from Strabo, _Antiq._, XIV, vii, 2.

[26] Mahaffy, _History of Egypt_, 92.

[27] Mahaffy, 93.

[28] Mahaffy, 192.

[29] Mahaffy, 145.

[30] Thackeray, St. J., _The Septuagint and Jewish Worship_, 11-13.

[31] Petrie, _Egypt and Israel_, 98-101.

[32] Josephus, _Cont. Apion_, ii, 5.

[33] _Antiq._, XII, iv.

[34] Mahaffy, 192-3.

[35] _Wars_, I, ix, 4.

[36] _Cont. Apion_, ii, 5, end.

[37] _Wars_, II, viii.

[38] Petrie, _Personal Religion in Egypt_, 63.

[39] _Pers. Relig._, 38.

[40] _Antiq._, XIV, viii.

[41] Milne, _History of Egypt_, 16.

[42] _Antiq._, XVIII, viii.

[43] Milne, 29, 30.

[44] Milne, 31, 32.

[45] _Antiq._, XIX, v. 2, 3.

[46] Acts xviii. 1.

[47] Milne, 35.

[48] _Wars_, II, xviii, 8.

[49] Milne, 52.

[50] Dion Cassius, Trajan, end.

[51] _Wars_, VII, x, 4.

[52] _Wars_, VII, x, 1.

[53] Milne, 98-9.

[54] Stanley Lane-Poole, _History of Egypt_, 11.

[55] Lane-Poole, 127.

[56] Lane-Poole, 301.

[57] Lane-Poole, 137.

APPENDIX

ANCIENT HEBREW PAPYRI

PROVISIONAL TRANSLATION BY DR. H. HIRSCHFELD

FRAGMENT A

LINE

1. (relic of selah [?]).

2. Wells ... hewn ...

3. To lead ... to this ...

4. They rejoice ... they decay ...

5. In the light, or (with ח added) the path ...

6. Of the Temple ... He has put to shame ...

7. They trembled, languished, turned to Thee ...

8. With glee and holy convocation ...

9. In the assembly of holy myriads ...

10. When mountain peaks frowned (see Psalm lxviii. 16-17) ...

11. Myrrh and cinnamon ...

12. I am inundated with tribulation ...

13. ...

14. Kings ...

15. Engraved.

16. Remember and ...

17. ?

(_Probably a lament on the destruction of the Temple._)

FRAGMENT B

1. ?

2. surrounding (?)

3. ?

4. path ?

5.

6. upon the earth (land ?).

FRAGMENT C

1. ? ?

2. ?

3. ?

4. ... males ...

5. ... and avenge the sanctuary ...

6. Thou hast ... ? us a kingdom of priests ...

7. ... a kingdom ... ?

FRAGMENT D

1 to 5. illegible and untranslatable.

6. Joel ... ?

7. And Nehemiah. Nahor ... ? in judgement (?).

8 to 10. illegible ...

* * * * *

_Printed in Great Britain by_

UNWIN BROTHERS, LIMITED

LONDON AND WOKING

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of The Status of the Jews in Egypt, by

W. M. Flinders Petrie

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE STATUS OF THE JEWS IN EGYPT ***

***** This file should be named 56444-0.txt or 56444-0.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/5/6/4/4/56444/

Produced by MFR and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive

specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this

eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook

for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports,

performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given

away--you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks

not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the

trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the

person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph

1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the

Foundation" or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg-tm License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work

on which the phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the

United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you

are located before using this ebook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including

any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access

to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format

other than "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official

version posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site

(www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense

to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means

of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original "Plain

Vanilla ASCII" or other form. Any alternate format must include the

full Project Gutenberg-tm License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

provided that

* You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed

to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he has

agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid

within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are

legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty

payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in

Section 4, "Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation."

* You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all

copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue

all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg-tm

works.

* You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of

any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of

receipt of the work.

* You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work or group of works on different terms than

are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing

from both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and The

Project Gutenberg Trademark LLC, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

works not protected by U.S. copyright law in creating the Project

Gutenberg-tm collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may

contain "Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate

or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other

intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or

other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or

cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium

with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you

with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in

lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person

or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second

opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If

the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing

without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO

OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT

LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of

damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement

violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the

agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or

limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or

unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the

remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in

accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the

production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses,

including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of

the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this

or any Project Gutenberg-tm work, (b) alteration, modification, or

additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any

Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of

computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It

exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations

from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future

generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see

Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at

www.gutenberg.org Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by

U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is in Fairbanks, Alaska, with the

mailing address: PO Box 750175, Fairbanks, AK 99775, but its

volunteers and employees are scattered throughout numerous

locations. Its business office is located at 809 North 1500 West, Salt

Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email contact links and up to

date contact information can be found at the Foundation's web site and

official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

[email protected]

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND

DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular

state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To

donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project

Gutenberg-tm concept of a library of electronic works that could be

freely shared with anyone. For forty years, he produced and

distributed Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of

volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as not protected by copyright in

the U.S. unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not

necessarily keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper

edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search

facility: www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.

The Status of the Jews in Egypt - The Fifth Arthur Davis Memorial Lecture

Subjects:

Download Formats:

Excerpt

Project Gutenberg's The Status of the Jews in Egypt, by W. M. Flinders Petrie

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are...

Read the Full Text

— End of The Status of the Jews in Egypt - The Fifth Arthur Davis Memorial Lecture —

Book Information

- Title

- The Status of the Jews in Egypt - The Fifth Arthur Davis Memorial Lecture

- Author(s)

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders (William Matthew Flinders)

- Language

- English

- Type

- Text

- Release Date

- January 27, 2018

- Word Count

- 9,844 words

- Library of Congress Classification

- DS

- Bookshelves

- Browsing: Culture/Civilization/Society, Browsing: History - General, Browsing: History - Religious

- Rights

- Public domain in the USA.

Related Books

Egyptian decorative art

by Petrie, W. M. Flinders (William Matthew Flinders)

English

360h 53m read

Methods & Aims in Archaeology

by Petrie, W. M. Flinders (William Matthew Flinders)

English

940h 22m read

Janus in Modern Life

by Petrie, W. M. Flinders (William Matthew Flinders)

English

508h 20m read

The Arts and Crafts of Ancient Egypt

by Petrie, W. M. Flinders (William Matthew Flinders)

English

603h 2m read

Ten years' digging in Egypt, 1881-1891

by Petrie, W. M. Flinders (William Matthew Flinders)

English

685h 14m read

The Religion of Ancient Egypt

by Petrie, W. M. Flinders (William Matthew Flinders)

English

376h 58m read